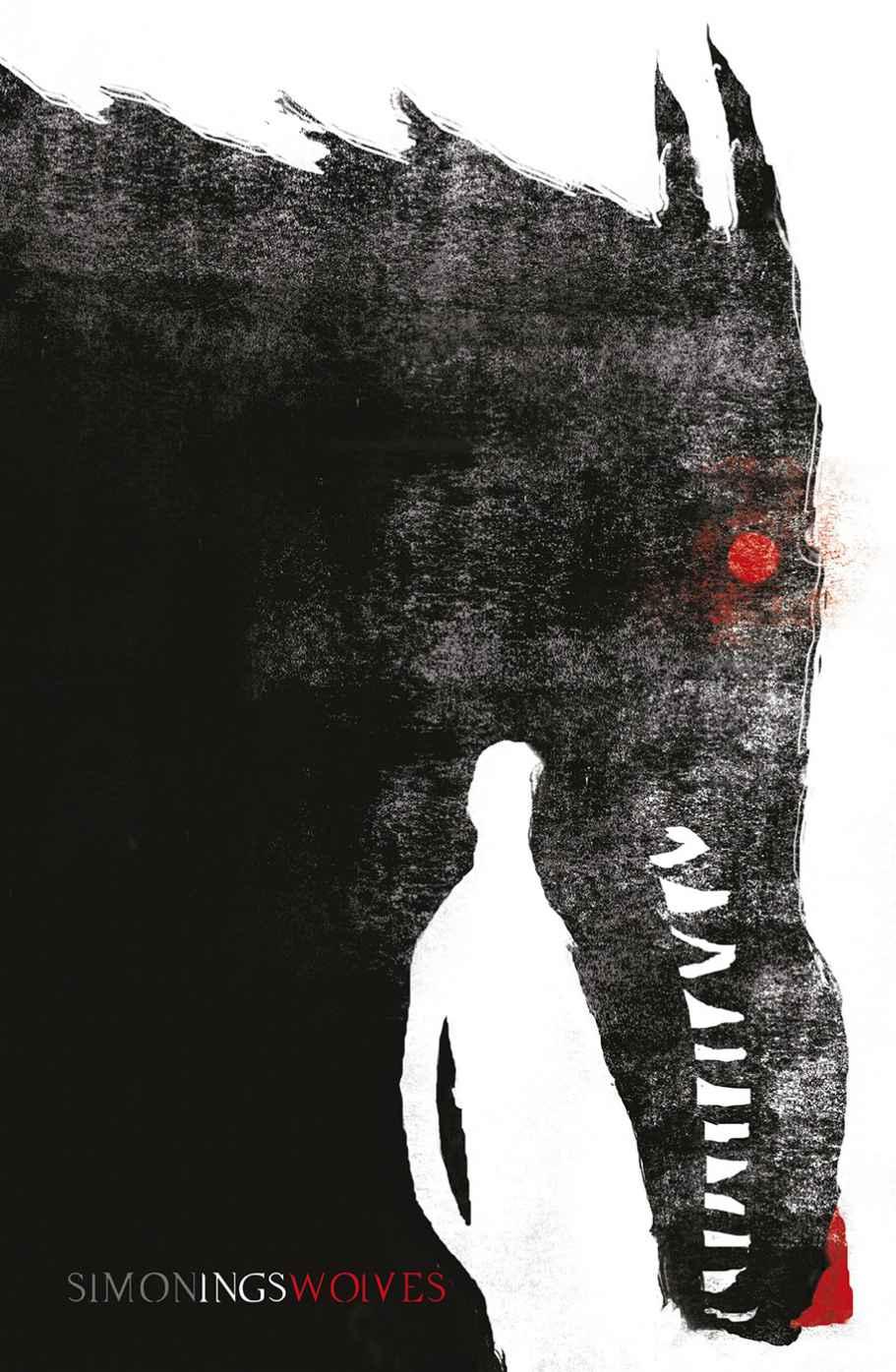

Wolves

for Mark and John,

and for my brother Richard:

the truth will out.

SIMON INGS

ONE

H

is phone call had to come, of course, hard on the heels of the accident and Mandy’s maiming, and a life reduced to routines around special cleansers and prophylactic socks. ‘How the devil are you?’ he says, very hail-fellow-well-met.

Michel and I were best friends at school, and I have swapped desultory messages with him over the years. I have said ‘Call me when you’re in town.’ (But he says he has a horror of cities.) The last time we talked I was still living in the old locomotive factory. Kicking rubbish out the way of my front door each evening. Ringing in food. Working into the night, rocked to sleep at last by sirens and breaking glass.

I fall back, sprawling across the sofa, trying to parse what he is saying. The line is clear enough but for some reason I am finding it hard to work out where one word leaves off and the next begins.

What would he make of this place, I wonder? The floorboards are warm and smoothly waxed. The rug is so thick it needs mowing. The coffee table is a sheet of reinforced glass balanced on four gigantic marbles. The television is part of the wall. Explaining all this to Michel – explaining that this is all Mandy’s, not mine – would involve us in a series of nod-and-wink, good-on-you-mate exchanges wholly at odds with the real tenor of my life. The sleepless nights. Feelings of impotence. The smell.

Michel’s sending video with his call. He’s sitting in virtual darkness, and the gain’s boosted into the uncanny in an attempt to render his face. It shines out of the glass in my hand like an amber traffic beacon.

I don’t reciprocate. Imagine the picture I would make: my death’s-head, can’t-complain rictus; and behind me, unnoticed, Mandy walks by on her way to the kitchen, swinging her big clown hands. Her raggy face.

Where is he, exactly? The setting is unreadable: a mass of shadows and angles. The devil in his smithy. ‘Can’t complain,’ he grins. His teeth are in shadow – a crackling grey lightning in the maw of his mouth.

Caught between two worlds, I find it difficult to carry communication between them.

Not difficult. Impossible.

‘We wondered if you’d like to come up.’

Come up. Come up

?

‘We’ve a cottage. And – get this. A boat.’

Who’s “we”? ‘The thing is . . .’

‘Yes?’

‘The thing is, Michel, I’m a little bit fucked.’

Laughter. Of course. He doesn’t know.

‘Mick, I’ve been in an accident.’

A pause. ‘Bloody hell. What happened? Are you all right?’

Well. I don’t know what to say.

Am I all right?

‘Who was that on the phone?’

‘An old friend.’

‘Yes?’

‘From work, Mandy. No one important.’

‘I’m going to bed,’ she says.

‘All right. Do you want me—’

‘No, I’ll do it myself.’

‘Well. Okay.’ I lever myself up from the sofa and walk out onto the rear terrace. ‘I’ll be through in a minute.’

Mandy’s house is set among tall white mansions, on a crescent with a private park. A canal runs at the back of her house, and rowing boats varnished the colour of honey are secured with exotic bike locks to the poles of private jetties. Sometimes young women with expensive feathery haircuts pass by, girls really, sculling the narrow water in boats as sharp and thin as slivers of bone.

Of course at this time of night there’s no one around at all.

I’ve been living at Mandy’s for nearly a year. I knew from the start it was a mistake. I was quite happy where I was, in my little conversion flat high in the eaves of the old locomotive works, on the other side of the city.

Mandy hated the place. After climbing all those heavy stairs, ‘Is this all there is?’ A view of brick-paved courtyards, fly-tipped mattresses, an occasional bicycle. This was not snobbery, I realise now, but a failure of the imagination.

‘Conrad.’

Mandy writes. She performs her own poetry on a women’s magazine programme on the radio, rubbing up against some horrendous scoop about clitoriclectomy, perhaps; an interview with an upcoming singer-songwriter; witty pieces about vests and soup.

‘Conrad, come and help me.’

Most of the things from my old flat are in storage. We don’t need them here. I should have just thrown my chipboard furniture away; it would have been cheaper than paying storage every month.

‘Help me get undone.’

One piece of mine has made it as far as Mandy’s bedroom. My mother’s mirrored dressing table was the first item my parents bought for themselves after their wedding. They came across it on their honeymoon in the mountains. Goodness only knows how it had fetched up there. The drawer fronts, the table-top, even the legs are scaled with glass. Mounted on the back and sides of the table are three large cantilevered mirrors. The central mirror has a white-painted wooden frame studded with light sockets. I can’t imagine what Dad expected me to do with it in my tiny flat. He must have thought I would sell it.

How could I possibly sell it?

‘I need some help with these,’ says Mandy, holding up her arms.

When we fall in love with someone, we fall in love first with their world. Sometimes love for the person follows.

Sometimes not.

Mandy and I used to drive out through the forest in search of up-market boot fairs. Every time we rode over a steep bridge, or round a sharp bend, or through a tunnel, Mandy tooted her horn ‘to warn oncoming traffic’. It was charming at first. Toot toot. Alongside gorges, over high saddles. ‘Toot toot.’

‘It’s what the horn is for,’ she insisted. She was so frantic to be in the right, she would make up things to be right about. We pulled up at a T-junction. ‘Well?’

‘Well, what?’

‘Are you going to tell me if it’s clear on that side?’

‘Just drive.’

‘I can’t see.’

‘Learn. How do you manage when I’m not in the car?’

‘When you’re not in the car I can see out of the window.’

‘Oh, fuck off. Drive. Actually, don’t. Stop. Stop the car.’

‘Don’t be so childish.’

I tugged at the door. She had put the child lock on. She gunned the engine and we kangarooed into the road.

It went dark. The air shot out of my lungs. It froze into glass and washed over my face. There was a single, sharp retort – one steel rod striking another. The engine found its voice and started to warble. The car spun and rolled over. A scaffolding rod shot through the cabin of the car. I rested my head against it. The metal was cold and rough against the back of my head. There was another, more complex impact – a plastic eggbox crushed slowly under a heel. Mandy sang along with the engine. I opened my mouth to join in and a piece of glass embedded itself in my tongue.

This, when at last they cut us out, is what they found to say about me:

‘Contusions. Bleeding from the mouth.’

Mandy’s notes – I have seen them – are stored in a binder as thick as my fist. Mandy being Mandy, she read them cover to cover, policing her care. I turned the pages for her. ‘You missed one.’

‘I didn’t.’

‘You turned two over. There.’

‘Right.’

‘You see?’

‘Yes.’

‘Now get your hands away.’

My hands are always getting in the way. My hands are a necessary nuisance for her, now she has lost her own.

The straps around her arms are wet. She has been trying to unbuckle them with her teeth. This is what she is supposed to do; why, indeed, the straps are made of a flexible raw leather. But she needs practice – the hands are heavy, and she has not yet worked out how to cradle their weight while she undoes the straps. There is an art to this. This is what the physiotherapist said to Mandy at last week’s appointment. An ‘art’.

Mum’s old mirrored dressing table is unexpectedly useful to Mandy, now that she has to shed and reload limbs twice, sometimes three times a day. Whatever happens between us, I can see I’m never going to get the table back.

‘Hold still.’

‘Yes. Thanks, Conrad.’

The hands, electrically warm, more or less flexible, more or less intelligent, give and shift in my grip like freshly killed rabbits. I am very careful not to show any revulsion as I lay them on the table. ‘You want fresh socks?’

After a few hours’ wear, no matter how carefully she washes, the socks around the stumps of her wrists begin to smell. She uses all the gels. They lie across the mirrored surface of my mother’s table in bitter, medicalised parody of past times.

‘Shit.’

‘What?’

‘I haven’t done my face.’

I look into the mirror, see her china-white and staring. The fillers smoothing her scars require a special cleanser to loosen the collagen. The rest is routine enough. I know how to do this. ‘Let me help.’

Mum used to test her make-up on me in front of this mirror. On its bright glass surface, thumb-sized pots containing micas and gels were laid out like the controls of a starship. I can remember the feel of my mother’s fingers, the heat of her breath on my neck as she ran her brushes over me. Her laughter, and her head beside mine in the mirror, her eyes the same colour as mine. You could not tell us apart.

I

had grown up in a big, overblown red-brick inn built originally for commercial travellers plying the coastal resorts of the north-east. Mum and Dad had bought the business for well below the market rate when the bypass was announced. They had imagined that, with the road relieved and an uninterrupted view of water meadows under low chalk hills, city people would come and visit them for a bit of easily-accessed rural quiet. But even with the bulk of the traffic drawn away, the road was always too noisy to be ignored, and only a few years after their purchase the water meadows were grubbed up to make a housing estate.

When I was a child, I used to pretend to myself that I was growing up in the country. Once the water meadows were sold to developers, I had to come to terms with the fact that we lived in this weird, free-floating, light-industrial suburbia, unable to guess which of several nearby towns would swallow us first.

I never liked the housing estate. I tried to avoid it. I tried to avoid even looking at it. I rehearsed constantly the look and feel of how things

had

been. Buttercup games. Nettle stings. Mum’s impatience (‘You should have had a drink before we came out.’). The roil and bark of dogs someone had let off the lead to go snuffling after water rats. Sometimes there had been horses, their paddocks marked out with lazy fences – a couple of strings of barbed wire on rickety grey posts jammed in the ground. Mum would wrap a bit of old fruitcake in silver foil and let me feed the horses. When I closed my eyes, screwed them up tight, concentrated, these memories would parade past, always in the same order, as though, rather than naturally remembering, I was tuning into the same reassuring story, again and again.

Whenever I had to walk through the estate, I could feel my childhood recollections falling away from me, the way dreams fall away on waking.

My mum, whose name was Sara, poured everything she had inherited from her family into the hotel, then spent her whole life struggling to ‘recover her financial independence’. She had no idea – none – how to make money. I remember one spring I kept catching colds because I had to keep my bedroom window open all the time to get rid of the stench of clary sage – one of the more obnoxious essential oils she had convinced herself she could sell in industrial quantities to her friends. She even included that muck in her food sometimes – self-medicating again.