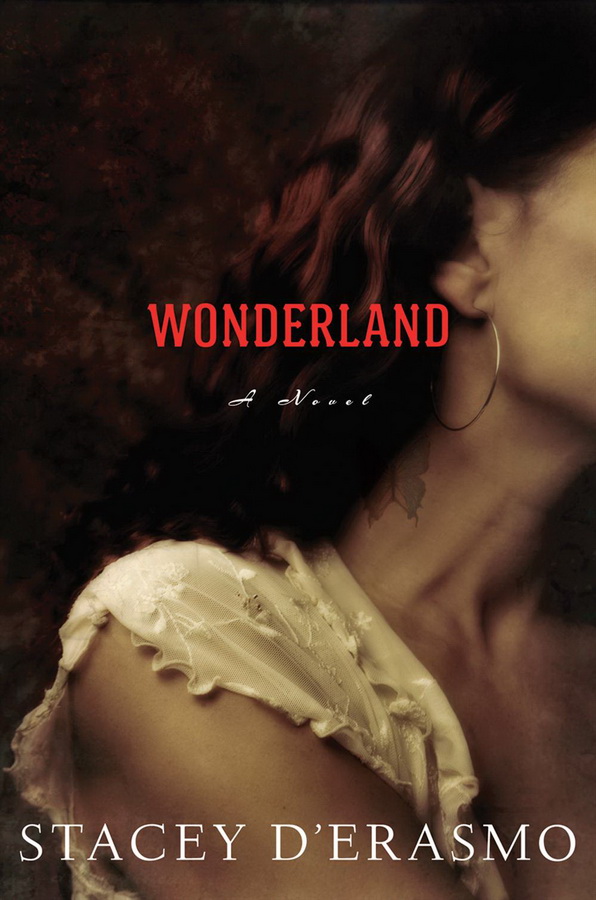

Wonderland

Authors: Stacey D'Erasmo

The Interior Motion of the Wave Remains

Wonderland, or, Why I Was Famous

My Father and I in the Musée de l’Orangerie

My Father Goes Back to the Mountain

Copyright © 2014 by Stacey D’Erasmo

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

D’Erasmo, Stacey.

Wonderland / Stacey D’Erasmo.—First U.S. Edition.

pages cm

ISBN

978-0-544-07481-1

1. Domestic fiction. 2. Psychological fiction. I. Title.

PS3554.E666W66 2014

813'.54—dc23

2013019523

e

ISBN

978-0-544-07369-2

v1.0514

For all my fellow travelers

The obvious analogy is with music.

—

LYN HEJINIAN,

My Life

Christiania

T

HERE IS A

man fixing a bicycle, or attempting to fix a bicycle, in the lane. I am sitting by the bluish window of a borrowed apartment in Christiania reading a paperback mystery badly translated from Italian. I bought it in the Copenhagen airport. It has something to do with boats—someone was murdered on a boat, salty types haunt the harbor—but I don’t care about boats.

I do find that I care about Christiania, which, though I’ve never been here before, feels familiar to me, as if I’ve dreamed of it many times. A good-sized island in the center of Copenhagen, surrounded by a river, it was taken over by hippies in 1971 and declared a “free state,” with communal property, no cars, and drugs openly for sale on the main drag, helpfully named Pusher Street. It has been a free state ever since. Now it is a leafy, semi-occluded place, with dirt roads, peculiar hand-built houses—some look like shacks, some look like spaceships—a few streets of stores selling crafts, and a climate all its own: it is warmer and damper here than in Copenhagen proper, as if one has stepped into a vast terrarium. Christiania, shaggy and rural and utopic, is a collective wish, under constant threat of being torn down by the government or turned into condos. There was a riot last week, apparently; a building was set on fire, it isn’t clear by whom, the anarchists or the cops. Christiania’s signature, its export to the unfree world, is innovative, handmade bicycles. Some of them look like the bicycles people, or aliens, might ride on Jupiter. Some of them look as if they were made by Dalí. Some appear to be anticipating a time when people will be much taller.

Christiania’s melancholic hope loops around my heart. It is the ruins of the future. As soon as we got here, the very first stop on the tour, my comeback tour—coming back from what to what, anyone might well ask—I wanted to stay. But we’re all leaving in the morning. We’re taking the train to Göteborg, whatever that is. In the living room of this borrowed apartment, five enormous windows made out of salvaged glass look onto the dirt road below. The light blue of the glass makes me wonder if it was salvaged from a church. Otherwise, the room is all bookshelves, a long curve of modernist red sofa, and two enormous, identical sleeping hounds with coarse gray fur. The old man with pink gauges in his earlobes who let me in told me not to worry about them, which I don’t, but I wish they would wake up. Instead, they lie on a chartreuse blanket on the floor, paws twitching in twin dreams. It’s cold in here. I would like to wrap a sleeping dog around me for warmth, but settle for a pair of fingerless knit gloves that I find on one of the bookshelves.

The bicycle wrench goes

cling clang

. . .

clingcling clang.

A loud screech, a ping. The man swears. I don’t speak Danish, but by the propulsive sound of the word he makes I know he’s swearing. I look out the window. Short, choppy yellow hair; tools and a sweater on the ground; a bicycle turned upside down, gears to the sky; his round face; a bit of a gut on him, though he’s young. Young

ish.

He drinks from a dark brown beer bottle, a slender wrench dangling from his other hand. He has stripped down to a T-shirt in his exertions; the indigo-blue edge of a tattoo is visible on one upper arm. He is handsome—almost too handsome.

My new young manager, Boone, looking, as usual, like he died two days ago, clatters up the wooden stairs and into the room carrying a small velvet bag. “Are you ready, Anna?” he says. “Sound check in an hour. Why did you turn off your phone? You should see where the rest of us are staying—this is

nice.

” Boone has a face like a chipped white plate. Small, round, questioning dark eyes. An ambivalent beard. A concave chest. He can’t settle, doesn’t sit down, hovering a few feet away. I would like to put him in my pocket and feed him crumbs.

“It’s cold,” I say.

“Not really,” he ventures. Boone is still trying to find his way around me. “Take a look at this.” He opens the velvet bag, unwraps tissue paper from a porcelain figurine—a vaguely Turkish-looking man who appears to be singing, smiling face uplifted, and playing a tiny porcelain guitar—which he sets on the coffee table. “Only a hundred fifty euros.” He rocks on his heels.

“Huh,” I say in what I hope is a neutral tone. Something about the figurine makes me uneasy—its uncanniness, its exorbitant price, its sentimentality. What is actually going on in the world if this kitschy thing is valuable?

“There was another one there, a Schiffener, but it wasn’t nearly as good. Why did you turn off your phone?”

“I don’t know,” I say, because I don’t. The jet lag makes me feel a beat or two behind myself. I pretend to go back to reading my book. Sardines, a bloody handkerchief. The pensive, hard-drinking, salty-tongued detective. It smells like licorice in this room; where did I leave it? I’d like some licorice.

“Anna,” says Boone. “I’ve been trying to call for an hour. What are you

doing?

Whose dogs are those? They look like van Stavasts—do you think they could be? It’s a really rare breed.”

“I don’t know.” I turn a page. I hate Boone, I think. “It’s too cold in here.”

Boone sighs. “Anna. Are you freaking out?”

I don’t respond. I’m not exactly trying to torment him. It’s just that, for one thing, I’m cold. I hate being cold. For another, I resent the implication, which underlies every exchange we have, that I should be grateful that he agreed to take me on. He’s said I must know how major I am, but we both know I went to him. All of Boone’s other acts are much younger, their beardless pallors glow, they have some sort of Icelandic/Berliner/post-polar-ice-cap handcrafted glamour, they wear peculiar Amish-like outerwear and badly fitting pants, only maybe two of them are junkies. They are all, of course, very serious. Brilliant, even. Their music is the music of the new world, coming over the waves, half translated. If you told me that they cobbled their own shoes out of scrap leather made from the tanned hides of cows they had butchered themselves with knives made in their own smithies, I would believe you. Many of them claim to be my lifelong fans, too, to have the lyrics from

Whale

engraved on their hearts, to be unreasonably devoted to my very shadow, but I can’t help feeling that if I were taxidermied and tied to the front of their tour buses, I’d be equally as lovable to them.

In my darker moments I feel like the Queen of England, bound and gagged by reverence. Tin-crowned and irrelevant. Perhaps I should stay here in Christiania, take up my other life, pass through the hemp-scented membrane of this place and become another Anna Brundage, maybe a better one. An Anna on a distended, futuristic bicycle. Also, for yet another thing, this entire idea was along the lines of a disaster. Music is quicksilver, gossamer; careers are measured in butterfly lifetimes. My butterfly life ended seven years ago in Rome. No one gives a shit about what I do anymore. I’m on a tiny label, albeit a tiny one with some cachet, but I paid for

Wonderland

myself. I begin to feel queasy. What have I started? I eye the sentimental porcelain figurine, singing so witlessly. Why did Boone agree to take me on? Am I a novelty act?

“I’m just cold. It’s too cold in here,” I say. “How’s the house?”

He scratches at his chin, grimacing. “Online sales are all right so far. It was a holiday yesterday, everybody was out drinking, we’re expecting more at the door. I mean, given who you are it’s going to be great, but it is the first one, and there’s a big World Cup match on TV tonight, you can’t—”

“Isn’t there any way to turn the heat up?”

Boone zips his sweater up to the neck in the way of a man who would like to strangle someone and is strangling himself instead. He puts the terrifying figurine back in its wrapping, its little velvet bag. “I have no idea. It isn’t my house.” He’s so aggravated that he’s barely speaking above a whisper. “I don’t even understand where we are. Is this island some kind of commune deal?”

“But I can’t sing if I’m too cold. You know that.”

“Anna. Darling. Put on a sweater. There will be heat in the theater. This place—it’s dirt roads, did you see that? It’s not so surprising that the heat doesn’t work that well.” He shifts his weight from one foot to the other. “But everyone is playing the Bee Palace right now. Right?” He regards me. “This is good.” How young he is. His beard barely on his face, he might scratch it right off one day. But he does work hard, he does.

“Christiania is a free state,” I offer as an olive branch of information. “The last one in the world, I think. We’re in the ruins of the future. Can you check on the heat at the theater?”

“Yes,” says Boone. “If you turn your phone on. Anna, it’s

nice

in here. You have the best one.” He gives me a significant, managerial look and clatters out. Also proving my point about the gratitude thing.

Beyond the salvaged blue window, the man is squatting next to the broken bike, smoking a cigarette and drawing lazily in the dirt with a stick. He is definitely almost too handsome. Daring myself to open the window, I open the window. I whistle. He lifts his face. “Hey. Want to come up for a beer?”