Worlds Enough and Time (19 page)

Read Worlds Enough and Time Online

Authors: Joe Haldeman

I’m getting better at delegating authority, not hanging all over my subordinates all the time. That’s partly a matter of sorting out who’s good at what and who enjoys what kind of work. If only the two factors would match up. But trusting other people to do their jobs gives me more time for the lit project and for my music.

That’s mostly clarinet and a little keyboard for theory. It will still be a while before I can play the harp again.

But it’s been more than two years. Think I’ll take it out now, and tune it, and see.

It was seven in the morning, 10 September 2103. O’Hara was asleep in John’s bed; John had been up reading for about an hour. Suddenly his console went blank and a loud buzzer sounded.

O’Hara sat up and rubbed her eyes. “What is it?”

“Trouble.” She unwound herself from the sheet and crawled sideways to read over his shoulder. The screen was blinking orange letters on a blue background:

10 Sept 03 | 9 Conf 304 |

EMERGENCY JOINT CABINET MEETING 0800

ROOM 4004

TELL NO ONE.

“Oh shit. What’s it going to be this time?”

“Good news, I’m sure.”

“You don’t have any idea?” She drifted over to the sink.

“You’re sleeping with the wrong guy for inside information.” He typed four digits and Dan’s image appeared, unshaven, blinking, groggy. “What’s up, bright eyes? You expect this?”

“No couple of things… but no. Look. I’m not alone.” He looked to the right and nodded. A woman’s faint voice said, “I won’t tell anyone,” and he watched, evidently until the door shut.

O’Hara pulled a brush through her hair with more force than was necessary.

“All right,” Dan said. “There’s two things. That labor organizer Barrett, she told Mitrione yesterday that she could pull off a general strike in the GPs.”

“Of course she could. I could do that. Half of them act like they’re on strike while they’re on the job. What else?”

“Well, there’s the rice shortage. Talk about rationing if they can’t get up to quota. But I thought that wasn’t for another month.”

“Yeah. Look, I’ll try a standard overall sys-check down through all the engineering departments; I do that most mornings anyhow. If I spot any anomalies I’ll call you back.”

“Okay.” He signed off and John pushed a button and said, “Sys-check.” The screen filled with acronyms and numbers.

O’Hara finished washing and stepped into a rumpled lavender jumpsuit. “Looks like no breakfast. I’m going down to 202; you want a roll?”

“Please, chocolate. Use my card; I’ll get the water going in a minute.”

“I’ll do it. You keep checking those old systems.”

“Love it when you talk dirty,” he said, without looking up or smiling.

She came back in five minutes with a couple of rolls and a box of orange juice. He was going through the data a second time. “Haven’t caught anything. It’s nothing obvious. Only this.” He stabbed a button five or six times, the data paging backward.

“They didn’t have chocolate. You can have cherry or apple filling.”

“Either one.” He took the roll and pointed at the screen with it. “The yeast farms asked for a fifty percent increase in both water and power allotment. That’s not really an anomaly, since we know there’s been a rice shortfall.”

“Oh goody. More fake tofu.”

“Rather have that than rice, myself.” He accepted a glass of juice. “If I’d known they were going to force-feed us rice for a century I would’ve stayed behind. Or eaten steak until I died of cholesterol poisoning.”

While John washed up, O’Hara went down to the laundry to get them fresh clothes. Half the Cabinet was waiting in line; so much for secrecy.

• • •

The year 2103 was the beginning of a two-year “Japanese takeover”; the Coordinators were Ito Nagasaki (Criminal Law) and Takashi Sato (Propulsion). They came into Room 4004 together, late, serious, and silent, looking tired. When the last Cabinet member had entered and found a seat, and the door hissed shut, Sato began without preamble:

“As most of you know, our rice production has been down for several months because of a persistent rust that has invaded all varieties. The ag people synthesized a virus specific to the rust, tested it in isolation for a few weeks, and it worked. So they inoculated the crop with it. That’s been a standard farming procedure for over a century.”

“Oh shit,” Eliot Smith said. “We’ve lost all the rice.”

“I’m afraid it’s worse than that, Eliot. Everything that photosynthesizes. Everything more complicated than a mushroom.”

There was a second of shocked silence. “We’re dead, then?” Anke Seven said.

“Not if we act quickly,” Nagasaki said. “Dr. Mandell?”

Maria Mandell rose. “We haven’t pinned down what happened. Some synergistic mutagen that was present in the crop but not in the lab. What happened is less important than what we’re going to do about it. I have every work crew from 0800 on, and every competent GP I can draft, at work harvesting and storing.”

“So by the time we leave this room,” Taylor Harrison said, “everybody aboard will know that the shit has hit the fan.”

“That’s right,” Mandell said. “They’d know before noon anyhow, with everything wilting.”

“What are the numbers?” Ogelby asked. “I know the yeast vats can’t keep the show going.”

“If all we had was this crop and what’s in storage, we’d have about a hundred and sixty kilo-man-days of vegetable food. That would keep the population going for eighteen days on reduced rations. Two months, on a starvation diet. There’s probably a similar amount of calories tied up in farm animals, if we slaughtered them all.

“The yeast vats produce enough food to keep about two thousand people alive indefinitely. If we could wave a magic wand and build eight more yeast vats, then the only problem would be that everyone would have to eat yeast derivatives until we were able to get the crops reestablished. But we can’t, of course. If we had the blueprints and the trained workers and the building materials all stacked up, it would be a matter of a few weeks. We don’t have any of those things.

“And we can’t be sure how long it will take to get things growing and harvested again. Everything we grow, and a few thousand other plants, exist in the form of genetic information, sealed away against any possible catastrophe, for Epsilon. But we haven’t yet reclaimed the knowledge to go from there to an actual plant.

“Food isn’t the only problem, of course. Breathing. The virus is also going to kill every plant in the park. No photosynthesis, no new oxygen, except what we manufacture ourselves. We can do it—we

have

to, in the process of turning carbon dioxide into nutrient solution for the yeast—but we can’t do it on a scale adequate for the whole population.

“We do have reference seeds for all of our food crops. Once we have the hydroponic beds cleaned out, the virus sterilized, we can start over on a small scale. But it will be more than two years, probably three years, before we’re back to anything like normal production.

“So about seven thousand of us have to volunteer for suspended animation. Perhaps I shouldn’t say ‘volunteer.’ There will be some people who will have to stay on to keep things going smoothly, or at all. First, though, about the suspended animation. Cryptobiosis. Sylvine?”

Sylvine Hagen stood up slowly. “Uh… I wasn’t prepped for this”

“Sorry,” Nagasaki said. “No time.”

“Well… I gave a presentation a couple of years ago; not much has changed since. It’s on a crystal; I’ll edit it and put it on everybody’s queue, code ‘crypto.’

“Here’s the basic fact: we have plenty of room for seven thousand people, but the recovery rate is not wonderful; seventy-five to eighty percent. We don’t have a lot of experimental data, but it looks as if the recovery rate is highest for people from their mid-twenties to their mid-forties. It rapidly declines after about sixty. It would probably kill anybody over eighty, eighty-five, and would definitely be fatal to anybody under nineteen or twenty; anybody still growing.

“Once you go in the box, you won’t come out for at least forty-eight years, which is about ten years before we arrive at Epsilon, of course.”

“There’s no way to hurry the process, or interrupt it?” Sato asked. “Assuming we can get the farms operating again.”

“Not that we know of. We’ll continue researching it.”

“‘We’? You don’t want to do it yourself?” Mandell said.

She reddened. “I

do

want to. I’m curious about it. And I’m fifty; I don’t want to put it off for too long. But I should stick around for a few years.”

“That’s a point,” Eliot said. “We

have

got some flexibility. How long does it take to get those coffins warmed up, cooled down, whatever?”

“Just hours. It’s an emergency facility.”

“So say we take everybody who’s somewhere between marginally helpful and certifiably useless, say five thousand people, and tuck them away this afternoon. We got enough yeast to feed half the rest. That leaves two thousand who have to go into the box sooner or later, basically living on the 160 to 321 kilo-man-days Mandell says we got. If they all ate regular rations, they could stick around for 80 to 160 days. That’s sayin’—to simplify the numbers—that the two thousand who aren’t goin’ in those coffins start eatin’ yeast tonight.

“But what we really got is like a decay function, exponential decay. I mean, say, half those people get their shit wrapped up in a week, go in the can. That leaves a thousand people to munch on what’s left. If I can do arithmetic, that means

they’ve

got 146 to 306 days’ worth. Then after a month, half of them go in. The five hundred left have got 232 to 552 days. And so on. Not like those numbers are that exact, but you get the picture.”

“Well put, Eliot,” Sato said. “A few people could stay for as long as ten years before going into cryptobiosis.”

“It may be moot,” Nagasaki said. “We may be hard pressed to find two thousand who wish to stay awake. To what extent do we make it voluntary? As Dr. Mandell said, certain people

must

stay, to keep the ship running smoothly and safely.”

“They have to stay at least long enough to train replacements,” Sato said. “Morales, this might be your domain. It falls somewhere between public health and propaganda. You see what I mean?”

Indicio Morales was in charge of Health Care. “I think so. You’ve got these two classes of people—the ones we want to go and the ones we want to keep awake. But each class is divided into those who themselves want to go or stay. So you want us to come up with some approach whereby everybody thinks they’re being heroes by doing what we want them to do. To sleep or not to sleep.”

“Exactly.”

“Well, we have psychologists. People who know about motivation, people who know about crowd psychology. But if anybody has propagandists, it’s Kamal.”

“We don’t have any propagandists,” Kamal Muhammed said. He was in charge of Interior Communications. “We have ‘public opinion engineers.’” Some people did laugh. “You get your shrinks together and I’ll get my manipulators and let’s meet for lunch.” He checked his watch. “Studio One, eleven-thirty?” Morales nodded.

“Good,” Nagasaki said. “In the meantime—right now, I guess—you take Mandell and Hagen down to prepare a brief public explanation. Just the plain truth about the crops and the need for swift action. Sato and I will be along in a few minutes.”

The three of them went to the door, which opened on a small murmuring crowd, including two police officers and two of Muhammed’s reporters. He made shooing motions. “Later, boys. Public statement down in One.”

The door closed on eerie quiet. “Well,” Sato said, “we have to come up with criteria, go or stay. Within our own specialties and in general.”

O’Hara spoke up. “Women with children should be allowed to stay. Men, too. The idea of waking up and having your child suddenly older than you are—it’s grotesque.” Daniel looked at her and nodded slowly, perhaps deciding.

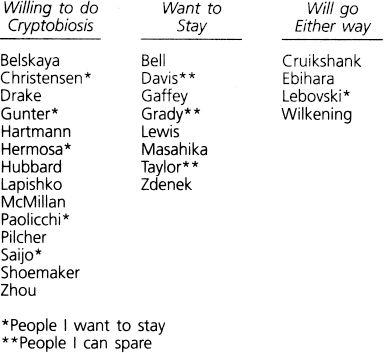

10 September 2103 [9 Confucius 304]—So ends one of the most hectic days of my life, of everyone’s life. I had until noon today to divide my staff into sleepers and wakers, trying for a four-to-one ratio. I canvassed them yesterday morning, and this is what I got (I’ll just copy in the memo):

Intercabinet Memo

Marianne O’Hara, Entertainment

10: 36, 10 Sept 03 (9 Confucius 304)

TO: Sylvine

RE: The list

Okay, you said you wanted a preliminary list. Mine is nothing but trouble. This is what I have for raw material—