Worlds Enough and Time (29 page)

Read Worlds Enough and Time Online

Authors: Joe Haldeman

Only Daniel was against it. He didn’t like the idea of the nature of their family life being dictated by some doctors’ schedules—by some doctors’ advance

perceptions

of their schedules, that could be wildly inaccurate. But Evy had the greatest stake in the question, since she was the only one planning to stay aboard ’Home after orbit, and she wanted to give the surgeons the go-ahead.

O’Hara was on the fence, nervous about okaying a life-threatening procedure, wanting the best for John, and selfishly wanting the whole mess to be settled one way or the other. How many husbands did she actually have—one, two, or one-and-a-fraction?

All three of them did agree that John’s attitude had been unambiguous. He would rather die than hang on alive but bound in the straitjacket of dumb paralysis.

O’Hara finally cast her vote with Evy, and they brought John out. At first it looked bad. His eyes opened, but he made no sign of recognizing his family, or anybody. The third morning, though, his eyes tracked O’Hara. She explained the situation to him and he nodded.

The operation took nine hours. Evy was not a surgical nurse, but she was allowed to attend as a supernumerary fetch-and-carry. She told O’Hara about an odd minute when she had to crouch under the table and hold a urinal for the senior surgeon, young enough to be her granddaughter, to straddle. It was scary: that child is trying to concentrate on brain surgery, my husband’s life literally in her hands, and at the same time convince her urogenital sphincter to overcome a lifetime of training and habit. But brain surgeons are used to long operations, even if Evy was not.

They had been warned that the results of the operation might not be apparent for some time, so nobody was alarmed when John didn’t show any immediate improvement. Within a week he had his yes-no-shit vocabulary back, and could also count up to ten. He was able to leave the hospital for his quarter-gee sickroom.

But he stayed at that level of verbal ability. After a month, the doctors conducted a series of tests and had to admit that the operation probably wasn’t going to make any difference. His brain was getting plenty of oxygen. It just wasn’t doing any good.

Age 55.43 [11 Theresa 428]—Actually, this starts about ten days ago. Too busy to write, molding young minds, perverting the will of die people, whatever.

They’ve put me in charge of the Induction section—Aptitude Induction Through Voluntary Hypnotic Immersion—on the reasonable basis that nobody else wants to touch it. Also, I was in charge of it back in Earth orbit, and actually went through the first half of the procedure myself, in the process of creating Prime.

That was 26 years ago, though, by my personal reckoning, and 66 years “real” time, or 147 Epsilon years. Most of half my lifetime, anyhow. I recall the process as sort of a vague bad dream; the administration of it, a waking nightmare.

But that’s not the problem now. There are a lot fewer people and I’m a better administrator than I was then. One problem is that more than three quarters of the Induction files are gone. Nine tenths were destroyed by New New’s information sabotage, and only a few replaced. Another problem is a lack of motivation.

Which is putting it mildly. It’s more like a consensus of rebellion. Induction is most effective on the young, and of course the best candidates are people who haven’t yet demonstrated a lot of talent in any useful field. So when you offer Induction to them, they get defensive. “I don’t want to be a welder, I want to be Myself!” Even though the only skill so far exhibited by Myself has been turning rations into compost.

One person who was not a problem, to my considerable relief, was Sandra’s husband Jakob. He doesn’t have any skills particularly useful for a primary settler—perfect pitch being irrelevant for the time being—so I showed him a list and he said plumbing looked interesting. He finished breakfast and kissed us both goodbye and went down to get reamed by the AI monster for two weeks.

Then there’s the problem of the Nowers, who actually

are

just compost machines. You could probably take one by the hand and wander along off to the machine, and he or she would smilingly obey, since everything is just now happening and is an expression of God’s will. But even those lumps have civil rights. The psychometricos call it “profound volitional incompetence,” which I think is a profound euphemism for lump. If they went through Induction, they might be able to rejoin the human race. But it’s more important, at least to some people, that they be allowed to worship in the quagmire of their choice.

Kamal Muhammed, the opinion engineer who helped us convince people to accept cryptobiosis for the common good, didn’t himself go into the can. He’s been in retirement for a long time, aged 105 in old years (233, Epsilon), but he still helps out now and then. I went to him for advice.

He must have one of the oddest-looking rooms in ’Home. For decades he has immersed himself in oriental arts and crafts. There are about fifty potted dwarf trees, bonsai, in a miniature forest that takes up all of the floor space except for narrow paths. The bunk where Muhammed sat was littered with worn paper folded and refolded into origami shapes. Set in the wall where most people would have a console and cube, he had an open square painted solid white. A vase with four flowers stood artfully offcenter, balanced in the space by a smooth stone, the size of a fist, mottled pink and gray.

“It’s beautiful,” I said. “The stone’s from Earth?”

He nodded. “Very perceptive. Japan. A friend has loaned it to me.” The rocks we used for landscaping in the park were from a carbonaceous chondrite asteroid; I didn’t remember ever seeing a pink one. “Let me demonstrate my own prescience: you have come to me because people are quite reasonably not doing what you want them to do. You want my skills to help you subvert them. For the good of the community of course.”

“Yes. But I would have come to you to see the trees, if I’d known about them.”

“You’ve been in crypto, or you would have known.” He pointed. “I place you. You served a term as Policy Coordinator.”

“Just shy of a hundred years ago. Epsilon years.”

“Of course.” He nodded thoughtfully. “And before that, in New New York, you were some sort of

enfant terrible

in Project Start-up. O’Casey, no, O’Hara, Marianne. You wrote a book. They put you in charge of Demographics for

Newhome

, a female Saint Peter at the Gate. Deciding who will ascend to the heavens.”

“You have a remarkable memory. I didn’t have the only say in Demographics, of course.”

“And you also worked with that terrible personality template machine. The one that puts wires through the eyeballs.”

“Not wires. Little sensors you can hardly feel.”

“And a tiny little probe up the rectum, one can hardly feel, I’m sure. Cozy catheters. And a comfortable tube down one’s throat. Exquisitely pleasing needles stuck in the arms. I have a feeling that this is what you want me to help you sell.”

“At least I’m not asking you to volunteer for the process yourself. Though I’m not sure whether we have templates for bonsai and origami.”

“There are books.”

“We’re mostly interested in less subtle talents, anyhow. Running heavy machinery, masonry, carpentry, metalworking. Skills that will condemn a person to a lifetime of hard labor on Epsilon.”

“Ah. ‘Skills that will reward a person with a lifetime of solid satisfaction, rebuilding civilization from the ground up.’ Or ‘Let the lazybones who stay in orbit live out their lives in a four-walled prison—give yourself a job that will give you freedom!’”

I had to laugh. “Did you just make those up?”

“It is a skill.” He smiled slightly. “One that guarantees I will spend all my days in a four-walled prison, which is what I vastly prefer.” He picked squares of paper off the bunk and stacked them neatly on a clear patch of floor. “Please sit. Let us investigate this problem.”

He was very helpful. The basic procedure for motivating somebody to do something unpleasant or dangerous was to separate out the various ways a person would benefit from doing it—sexual appeal, enhanced self-image, prospect of future comfort or security… all the way up to purely altruistic benefits such as the approval of God or to serve you generations yet unborn. He wrote down twenty-three separate areas of reward. The basic technique of opinion engineering was to figure out which of these areas would be most effective for your target population, and pack as many of them as practical into a single memorable statement. Pictorial associations at least as much as words; we’re not working with logic here.

I made a series of recorded appeals, using sexy young things of both and indeterminate genders, for lumberjacking and welding and so forth, which went on the Random Walk cube. But the “advertisements” weren’t scheduled at random.

People tend to watch cube at the same time each day, if they watch it. Most of the people I was seeking were more or less addicted to it. So I set them up several days in a row before each ad. I “primed” them, using Prime to help me search through the millions of small scenes in the Random Walk library. We came up with hundreds of pretty specific episodes extolling the pleasures of physical labor in the good old outdoors. Almost all of them in good weather. Maybe Epsilon does have good weather all the time.

None of the kids I’m after has ever experienced weather. Better remind them to take hats.

I should feel guilty about all this. But it’s fun, and ultimately to everyone’s benefit. As whoever invented television probably said.

PRIME

O’Hara talked it over with Evy and agreed that she would do most of John’s care-and-feeding during the months remaining until Epsilon. Evy would have him for years or decades after that. (Daniel was willing to help, but John resisted, sometimes violently; he obviously didn’t want another man to minister to him.)

She tried not to resent it as John eroded her time, assaulted her emotions. Moods were one thing he could communicate: for days he would alternate between rage and depression, and then there would be days of contrition, weeks of cooperation. Sometimes, in bittersweet silent communion, she felt she loved him as much as she ever had; other times—as she told me but not her diary—enslaved by his vulnerability, she helplessly wanted him to die. Years before, he had asked her to spare him a lingering painful death by providing him some means to end it. A handful of CNS depressants and a liter of boo; an intravenous pop of potassium chloride. She agreed in principle but, even then, wasn’t sure she would have the courage to do it.

She confessed to me that she thought of that sometimes, but he wasn’t in actual pain, and besides, if a quick death was what he wanted, he communicated well enough with expression and gesture to get across that simple idea. Maybe he felt that even a dim spark of life was worth living. Maybe he just wanted to spare her the awful decision.

Dr. Shawn suggested to her that John might be enjoying his enforced freedom from responsibility, and might even be feeling less physical pain than he had suffered all his life. Elderly patients with degenerative bone diseases often reported less pain, or even a complete cessation of pain, after a stroke or accident caused paralysis. It might not be a trade-off anyone would choose, but it was some compensation.

John had some use of his left hand, though all his life he’d been clumsy with it. He could manipulate the cube remote, but refused to have anything to do with the keyboard or any of the rehabilitative crafts projects that O’Hara brought him. He could read, but very slowly, and seemed to have a limited span of attention. He gave up on technical papers, with one exception: at the time of his stroke, John had almost finished writing his book-length history of the Deucalion project,

Sons of Prometheus

. O’Hara fleshed out his notes to complete the last two chapters, with John looking over her shoulder, sentence by sentence.

She found out that you could do a lot of editing with three words, if they were yes, no, and shit.

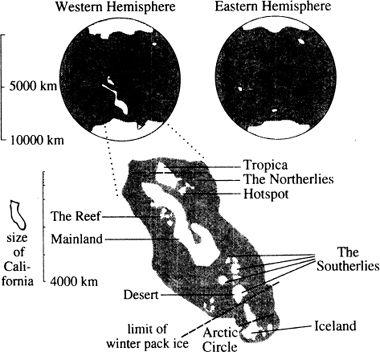

Three weeks out, they had the first fairly accurate chart of their water world. The Planetfall Committee released this map and sketchy description:

Better pictures are going to be available almost hourly, but this seems like a good time to start.

The smallest details we can see here are about ten kilometers wide; the tiniest island visible in the Reef is bigger than all of ’Home’s floor levels put together. The Mainland’s central lake has a greater area than Earth’s Lake Chad or Lake Superior.

The atmosphere is slightly less dense than Earth’s but richer in oxygen, which argues for a lot of plant life, if only phytoplankton. Nitrogen is the main inert element. There is a puzzling concentration of helium, over a thousand times the terran trace, but that shouldn’t have any effect on daily life, other than making balloon travel easy.

(Hotspot has a large active volcano, which could be a source of helium, though there’s no analog on Earth.)