Would You Kill the Fat Man (17 page)

Read Would You Kill the Fat Man Online

Authors: David Edmonds

In the 1970s there was a running gag in

Morecambe and Wise

, then Britain’s most popular comedy television program. Eric Morecambe and Ernie Wise would perform a series of sketches, but then, right at the end, having played no previous part in the show, a large woman called Janet would stroll onto the stage wearing a ball gown. She would shove Eric and Ernie out of the way and announce, “I’d like to thank you for watching me and my little show.” Jonathan Haidt sees reason as taking the role of Janet. It enters at the last minute, having done none of the work, and claims all the credit.

But, while Haidt believes that the emotions reign, others are not so sure: they view the clash between reason and emotion as a genuine tug of war.

CHAPTER 13

Wrestling with Neurons

The heart has its reasons, of which reason knows nothing.

—Pascal

Act that your principle of action might safely be made a law for the whole world.

—Immanuel Kant

“YOU STAND HERE in the dock, accused of killing a fat man. How do you plead?”

“Guilty, m’Lord. But in mitigation, my choice, my action, was determined by my brain, not by me.”

“Your brain decides nothing. You decide. I sentence you to impudence and ten years of hard philosophy.”

Lighting Up

In the past decade there has been an explosion of research into all aspects of the brain, driven by improvements in scanning technology. MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) scans have yielded intriguing results. The scanners work by detecting minute

variations in blood flow: when a particular part of the brain is engaged in more activity than in the so-called resting state it is shown, as neuroscientists put it, “lighting up.” Research is in its infancy, but the evidence is becoming overwhelming that particular bits of the brain are of particular use for particular functions. Subjects lie inside the large (and noisy) tubes and scans are taken while, for example, they listen to music or use language or navigate maps or imagine themselves engaged in various physical activities, or observe faces or artworks or disgusting creatures and objects like cockroaches and feces.

What happens in the brain when we make moral decisions is also under investigation—and because the trolley dilemmas give rise to such competing intuitive tugs, they’ve proved among the most popular of case studies. The preeminent superstar in this area is Harvard psychologist and neuroscientist Joshua Greene.

Greene was a debater at school, one who was instinctively attracted to utilitarianism. When a discussion hinged on the relative significance of individual rights compared to the greater good, he’d adopt the Benthamite rather than the Kantian line. The consequences were what mattered. But he was flummoxed when first confronted with the transplant scenario: surely it couldn’t be right to kill a healthy young man for use of his organs, even if this saved five lives. His utilitarian faith was shaken.

As a Harvard undergraduate he was introduced to the trolley problem—another baffling puzzle for a person of utilitarian persuasion. But, he says, it was only when he came across the peculiar case of Phineas P. Gage that he had his eureka moment. He was in Israel for his sister’s bat mitzvah, reading a book in his hotel room.

The Crowbar Case

Phineas Gage was a twenty-five-year-old construction foreman who would become a real, rather than hypothetical, victim of the railways. His job was to coordinate a group of workers who were building a railway track across Vermont. To make the route as direct as possible, the team would on occasion have to force an opening through rock. At 4:30 one summer afternoon there was a catastrophic accident. A fuse was lit prematurely. There was a massive blast, and the iron rod used to cram down the explosive powder shot into Gage’s cheek, went through the front of his brain, and exited via the top of his head.

That Gage was not killed instantly was miraculous. More miraculous still was that within a couple of months he seemed to be physically almost back to normal. His limbs functioned and he could see, feel, and talk. But it’s what happened next that transformed him from a medical curiosity into an academic case study. Although he was physically able to operate much as before, it became apparent that his character had been transformed—for the worse. Where he had once been responsible and self-controlled, now he was impulsive, capricious, and unreliable. It’s difficult to separate myth from reality, but one report says his tongue became so vulgar that the fairer and more delicate sex were strongly urged to avoid his company.

In his book,

Descartes’ Error

, the neuroscientist Antonio Damasio says Gage could know but not feel.

1

“This is it!” thought Greene, in his hotel room. “That’s what’s happening in the Footbridge and transplant cases. We

feel

that we shouldn’t push the fat man. But we

think

it better to save five rather than one life. And the feeling and the thought are distinct.”

Trained in both philosophy and psychology, Greene was the first person to throw neuroscience into the trolley mix. He began to scan subjects while they were presented with trolley problems: the scanners picked up where blips in the resulting brain activity took place.

Greene describes the trolley cases as triggering a furious bout of neural wrestling between the calculating and emotional bits of the brain. It’s a much more evenly fought tussle than that described by Haidt. Presented with the Fat Man dilemma, and the option of killing with your bare hands, parts of the brain situated just behind the eyes and thought to be crucial to feelings such as compassion (the amygdala, the posterior cingulate cortex, and the medial prefrontal cortex), move into overdrive. The idea of pushing the fat man “sets off an emotional alarm bell in your brain that makes you say ‘no, that’s wrong’.”

2

Without that metaphorical alarm, we default to a utilitarian calculus: the calculating part of the brain (the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and inferior parietal lobe) assesses costs and benefits of various kinds, not just moral costs and benefits. In Spur, the equation is not complicated: at the cost of one life we can benefit five.

A camera provides the basis for another helpful Greene metaphor. A camera has automatic settings—a setting for landscapes, say. That’s useful because it saves time. We see something we want to photograph and we press a button. But sometimes we want to mess around, try something fresh and unusual, be a bit arty and avant-garde. Perhaps we want the central image to be fuzzy. The only way we can achieve that effect is to switch to manual (calculating) mode. “Emotional responses are like the automatic responses on your camera. The flexible kind of action planning, that’s manual mode.”

3

The emotional parts of the brain are believed to have evolved long before the brain regions responsible for analysis and planning. In a moral dilemma one might therefore expect emotion to race more quickly to a conclusion than reason. Studies have shown that forcing people to go fast makes them less utilitarian.

4

That there appears to be a fight between two settings is nicely corroborated by a study involving what researchers call “cognitive load.” While subjects were considering the trolley problems, their cognitive processes were simultaneously engaged in another task—typically looking at (or adding) numbers that flash up on a screen. Under such conditions, subjects were slower to give the utilitarian answer, to kill the one to save the five in Spur (when the cognitive processes are engaged), but the task made no difference in the Fat Man dilemma, which principally engages the emotions.

The emotional recoiling that typically occurs when people contemplate killing the fat man is made up, Greene says, of two components. The first is an up-close-and-personal effect: there is something about the physicality of pushing, the direct impacting of another person with one’s muscles, that makes us flinch. The evidence suggests that this is even the case if the pushing doesn’t directly require contact with hands, but is achieved with a long pole that nonetheless uses similar muscles. The effect can be tested in the Trap Door case.

In the Trap Door scenario, we can stop the train and save the five lives by turning a switch (much like the switch in Spur). This switch opens a trap door on which the fat man happens to be standing. Now, while the most casuistically minded lawyer would be unable to identify any substantial moral distinction between killing with a switch and killing with a push, subjects asked about the trolley cases are more willing to send the fat man to his death when it involves the former rather than the latter. Still, whether it requires a switch or a push, most people still believe that killing the fat man is worse than changing the train’s direction in Spur.

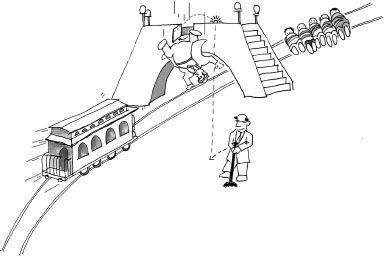

Figure 10

.

The Trap Door.

The runaway trolley is heading toward five people. You are standing by the side of the track. The only way to stop the trolley killing the five is to pull a lever which opens a trap door on which a fat man happens to be standing. The fat man would plummet to the ground and die, but his body would stop the trolley. Should you open the trap door?

Which means there must be something else going on too …

The second factor, says Greene, syncs nicely with the Doctrine of Double Effect. We are more reluctant to harm someone intentionally, as a means to a desired end, than to harm them merely as a side effect. These two factors—physical contact

and intent to harm—”have no or little impact separately, but when you combine them they produce an effect that’s much bigger than the sum of the separate effects. It’s like a drug interaction, where if you take Drug A you’re fine, and if you take Drug B you’re fine, but take them both together and BAM!”

5

Pushing the fat man, which combines a physical act with an intention to harm, produces this emotional BAM!

Evolutionary Errors

Greene has a compelling, if speculative, evolutionary explanation for the strange moral distinction people subconsciously draw between engaging muscles and turning switches. We have a particular revulsion to harms that could have been inflicted in the environment of our evolutionary adaptation. We evolved in environments in which we interacted directly with other human beings—force had to come from one’s own muscles. Using muscles to shove another person is a cue that there’s violence involved and for obvious reasons violence is generally best avoided.

These experiments focus on moral judgment, rather than behavior, on how people actually act. However, judgment and behavior are linked. And whether or not we buy into Greene’s evolutionary story, the psychology of killing has profound significance beyond the academic realm of trolleyology. The skies over Pakistan and Afghanistan are regularly crisscrossed by unmanned U.S. aircraft, drones, operated from thousands of miles away in the United States, usually by relatively young men. Up to 2,680 people may have been killed by U.S. drones in Pakistan alone in the seven years prior to 2011.

6

Drones represent the future of warfare: currently some drones are used for reconnaissance, while others target people and buildings. Whether we find it easier to kill by moving a joystick or by puncturing a throat with a bayonet is by itself a morally neutral discovery. After all, if we face a deadly enemy we may want our soldiers to feel less compunction about killing. But if it’s true, as it seems to be, that we can more easily kill by flicking a switch than by thrusting with a bayonet, then that’s something we need to know about.

This debate fits into a wider discussion about how well (or badly) evolution has equipped us ethically for the modern age. Philosophers, particularly of a utilitarian persuasion, have highlighted the following apparent inconsistency. If we walked past a shallow pond and saw a young child drowning, most of us would instinctively jump straight in to rescue her. We would do so even if we were wearing expensive clothes. We would be outraged by an observer who stood idly by as the child thrashed about and who later explained that she couldn’t possibly have plunged in because she was wearing her favorite Versace skirt that had cost $500. Yet few of us respond to letters from charities who point out that similar amounts of money could save lives on the far side of the world.

There doesn’t seem to be an obvious ethical difference between saving a stranger in front of us and saving one far away. But there’s a plausible evolutionary explanation for our contrasting reactions. The modern human brain evolved when humans were hunter-gatherers, living in small groups of between 100 and 150. It was of benefit (in evolutionary terms) to care for our offspring and the few others with whom we cooperated. We didn’t want or need to know about what was happening on the far side of the mountain, valley, or lake. Technology now brings us instant news of catastrophes elsewhere in the world. That we’re so uncharitable in responding to such events

is hardly surprising—even if it’s morally indefensible. Peter Singer gives the following trolleyesque example: