Would You Kill the Fat Man (9 page)

Read Would You Kill the Fat Man Online

Authors: David Edmonds

Anscombe set about minutely dissecting the ways we use intentionality in language: for example as an adverb (“the man is pushing intentionally”), a noun (“the man is pushing the fat man with the intention of toppling him over the bridge”), and

verb (“the man intends to push the fat man”). Most of Anscombe’s complications need not concern us, but she was the first to point out that an action can be intentional under one description yet not under another. The action of the person who sends the fat man hurtling off the bridge can be intentional under the description “pushing the fat man,” but not under the description “stretching his triceps.” Of course, the pusher of the fat man does stretch his triceps, but it would sound peculiar to say that he

intended

to do so. If you asked him for an explanation of his action he would be unlikely to respond, “I did it to stretch my triceps.”

So did soldiers mean to kill the Pullman rioters? No soldier was ever held responsible for doing so. The tone of the commission report is hardly sympathetic to the victims. The mobs that took possession of the railroad yards and tracks were, it states, “composed generally of hoodlums, women, a low class of foreigners and recruits from the criminal classes.”

6

Those hauled in to give testimony to the commission describe the troops as meaning to “protect property,” or meaning to “preserve the law.” No doubt that is how the individual soldiers would have responded if asked why they used their weapons: “I meant to keep the peace,” “I intended to stop the riot,” “I meant to prevent interference in interstate trade.” But how can you fire into a crowd and not intend to kill? Did they merely intend to wound? Was the killing foreseen but not intended?

There is a deep problem here, which Cleveland’s granddaughter, Philippa Foot, raises in her original trolley article. She calls it the problem of “closeness”—and refers to the cave case. Recall that in the cave the waters are rising, the fat man is blocking your escape, and you have a stick of dynamite that would clear a route for you and others but obviously end the fat

man’s life. Suppose you used this dynamite and afterward declared in court that you’d had no intention of killing the fat man, merely of blowing him into a thousand small pieces. That, says Foot, would be “ridiculous.”

7

Blowing a man into a thousand pieces and killing him are one and the same: drawing a distinction between them would be risible. But then we require an account of “closeness” to ensure that such excuses are indeed laughed out of court—and it has proved notoriously tricky to provide one. After all, if talented surgeons were to arrive on the scene and declare that they could somehow stitch the fat man back together, you would be delighted. So it must be true, in this strange sense, that you really don’t want the fat man to die.

This is similar to the situation in Loop. It could be said that in turning the train we don’t strictly speaking intend to kill the man on the loop. Our intention is merely that he be hit and that the train stop: if the train came to a halt after contact with the man, but he miraculously survived, and then wandered off without so much as a sprained thumb, we wouldn’t chase after him with a club in order to beat him to death. We wanted the man to obstruct the train, not to die.

However, as Philippa Foot points out, in practice being hit by a train is a death sentence: to draw a distinction between colliding with and killing a person feels sophistical.

Extra Push

Putting aside the problem of closeness, intentionality, as we’ve seen, can draw a distinction between Spur and Loop. In

The View from Nowhere

, Thomas Nagel describes certain types of action as being “guided by evil.”

8

One way to make sense of this is to think counterfactually—about “what ifs.” What if the man on the Loop were to run away, for example? Nagel writes that if one is guided by an evil goal, “action aimed at it must follow it and be prepared to adjust its pursuit if deflected by altered circumstances.”

9

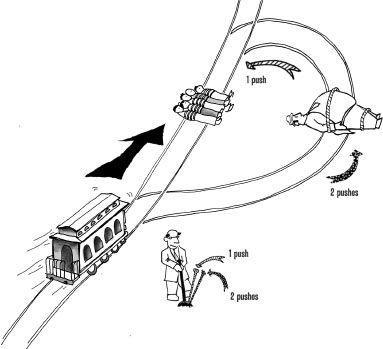

Figure 6

.

Extra Push.

The trolley is heading toward the five men who will die if you do nothing. You can turn the trolley onto a loop away from the five men. On this loop is a single man. But the trolley is traveling at such a pace that it would jump over the one man on the side track unless given an extra push. If it jumped over this man, it would loop back and kill the five. The only way to guarantee that it crashes into the man is to give it an extra push. Should you turn the trolley, and should you also give it the extra push?

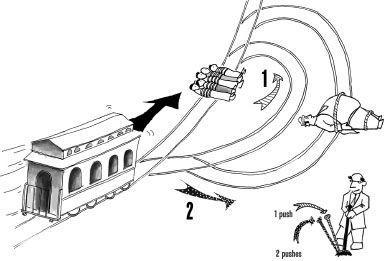

Figure 7

.

Two Loop.

The trolley is heading toward five men who will die if you do nothing. You can redirect the trolley onto an empty loop. If you took no further action, the trolley would rattle around this loop and kill the five. However, you could redirect the trolley a second time down a second loop that does have one person on it. This would kill the person on the track but save the five lives. Should you redirect the trolley, not once, but twice?

The “what if” question helps us think about intentionality. For example, take the Extra Push

10

case.

In Extra Push, you can turn the train onto the loop away from the five men, but the train is traveling at such a pace that it would jump over the one man on the side track unless given an extra push. If it jumped over this man, it would loop back and kill the five. The only way to guarantee that it crashes into

the man is to give it this extra push. If you give the train this extra push, it seems clear that you would be aiming to hit the single man. Similarly, in the Two Loop case.

In Two Loop you can redirect the trolley onto an empty loop. If you then took no further action, the trolley would rattle around this loop and kill the five. However, you could redirect the trolley a second time down a second loop which does have one person on it. This would kill the person on the track but save the five lives.

Were you to redirect the trolley not once, but twice, to guarantee its collision with the single man on the track, it would surely be preposterous to claim that you didn’t

intend

to hit him.

11

The Knobe Effect

There is one final complication with the concept of intention, unearthed by a new philosophical movement, called “experimental philosophy” or “x-phi” for short, of which more soon. If we’re trying to work out whether somebody

intended

to produce a particular effect, we might think that essentially all we needed to do was establish that person’s mental state, what the person wanted or believed. But a young philosopher and psychologist, Joshua Knobe, asked subjects about the following two cases—and came up with a surprising result, now known as the Knobe Effect.

• CASE 1: A vice president of a company goes to the chairman of a board and says, “We’ve got a new project. It’s going to make oodles of money for our company, but it’s also going to harm the environment.” The chairman

of the board says, “I realize the project’s going to harm the environment. I don’t care at all about that. All I care about is making as much money as possible. So start the project.” The project starts, and sure enough, the environment suffers.

• CASE 2: A vice president of a company goes to the chairman of a board and says, “We’ve got a new project. It’s going to make oodles of money for our company. It’s also going to have a beneficial impact on the environment.” The chairman of the board says, “I realize the project’s going to benefit the environment. I don’t care at all about that. All I care about is making as much money as possible. So start the project.” The project starts, and sure enough, there is a beneficial impact on the environment.

The question subjects were asked was whether in each case the chairman

intended

the effect on the environment. And here’s the curious part. When asked about the first scenario, most people say “yes, the harm was intentional.” But did the chairman in the second scenario intentionally help the environment in the second scenario? Most people thought not.

This is odd, since the two cases seem almost identical. The only difference is that in the first case the chairman has done something bad, and in the second case he has done something good. Knobe believes this shows that the concept of intention is inextricably bound up with moral judgments. More generally, he maintains that such results suggest we should radically rethink how we regard ourselves. We do not function like the ideal scientist, who tries to make sense of the world from an entirely detached perspective. Instead, our way of understanding what goes on is “suffused with moral consideration”

1

: we see the world through a moral lens.

If after all this the concept of intention is enough to make your head spin like a lazy Susan, then take comfort in the fact that one branch of philosophy has no truck with any of these nuanced distinctions between acts and omissions, positive and negative duties, intended and merely foreseen effects. It takes its inspiration from a figure whose skeleton, bulked up with hay and straw and cotton and lavender (to keep the moths away) and dressed in a jacket and white ruched shirt, sits in a glass-fronted case off Gower Street in the heart of London. A walking stick, which was given a pet name, Dapple, rests in the case too. If the body were to spring to life, it could provide an instant response to the Fat Man puzzle. There would be no agonizing, no grappling with conscience. For the founder of utilitarianism, the appropriate action would be self-evident.

CHAPTER 8

Morals by Numbers

It is the greatest good to the greatest number of people which is the measure of right and wrong.

—Jeremy Bentham

He was not a great philosopher, but he was a great reformer in philosophy.

—John Stuart Mill on Bentham

JEREMY BENTHAM (1748–1832) requested in his will that his cadaver be dissected for scientific research. He was friendly with many of the founders of University College, part of London University, where his Auto-Icon, as he called it, can still be seen. His skeleton was preserved. The stuffed body has a wax head with piercing blue eyes, crowned with a fetching wide-brimmed hat: the real head, which kept being pinched by student pranksters, is now under lock and key. One legend, that in the past the Auto-Icon was wheeled out for college governing meetings, where it was registered as “present but not voting,” appears, alas, not to be true.

Bentham’s strange afterlife befitted his eccentric life. His oddness was manifest in his idiosyncratic use of language. Rather than go for a walk before breakfast, he would announce

his intention to have an antejentacular circumgyration. He was devoted to a senescent cat, whom he’d named the Reverend Dr. John Langborn.

In what is surely the most curious family linkage in the history of philosophy, Jeremy Bentham had a close friend James Mill, and acted as a guardian figure for Mill’s son, who himself would become an acclaimed philosopher, John Stuart Mill. John Stuart Mill had a godson who was one of the most important philosophers of the twentieth century, Bertrand Russell. Mill had reservations about Bentham’s philosophy, but nonetheless described him, in what was intended as a compliment, as the “chief subversive thinker of his age.”

1

And Russell was a fan of Bentham’s too. He gave him credit for many of the more enlightened reforms undertaken in Victorian England. “There can be no doubt that nine-tenths of the people living in England in the latter part of last [the nineteenth] century were happier than they would have been if he had never lived,” Russell wrote, before adding a characteristic quip: “So shallow was his philosophy that he would have regarded this as a vindication of his activities. We, in our more enlightened age, can see that such a view is preposterous.”

2