Writing the Breakout Novel Workbook (21 page)

Read Writing the Breakout Novel Workbook Online

Authors: Donald Maass

Also in the last chapter, I mentioned Nora Roberts's very different novel,

Carolina Moon.

As we know, in this story Roberts creates five plot layers— that is, big problems—for her heroine, gift store owner Tory Bodeen, to overcome: (1) the crippling memory of the brutal beatings her father administered to Tory as a child; (2) the unsolved rape and murder of Tory's childhood friend Hope Lavelle; (3) the second sight that plagues Tory with painful visions of the suffering of others; (4) Hope's killer still at large, killing others, and now after Tory; (5) a love interest who is unwanted by Tory.

How does Roberts weave these plot layers together? Principally by having characters cross from one storyline to another. For instance, Tory's murdered childhood friend had an older brother, Cade Lavelle. Whom do you think falls in love with the adult Tory when she returns to her hometown? Bingo. Cade draws together the murder in Tory's past and the problem of her resistance to men.

A further node of conjunction is that Cade's mother, Margaret, and Hope's surviving twin sister, Faith, are not at all pleased by Tory's return to the town of Progress; indeed, they blame Tory for Hope's death, since it was a nighttime adventure jointly planned by Tory and Hope that drew Hope to the woods where she was murdered. In the present, Faith takes her hatred of Tory so far as to try to sabotage Tory's effort to heal from the beatings her father inflicted (layer one), as we see the first time Faith confronts Tory:

"You believe in fresh starts and second chances, Tory?"

"Yes, I do."

"I don't. And I'll tell you why." She took a cigarette out of her purse, lighted it. After taking a drag she waved it. "Nobody wants to start over. Those who say they do are liars or delusional, but mostly liars. People just want to pick up where they left off, wherever things went wrong, and start off in a new direction without any of the baggage. Those who manage it are the lucky ones because somehow they're able to shrug off all those pesky weights like guilt and consequences."

She took another drag, giving Tory a contemplative stare. "You don't look that lucky to me."

Yet another node of conjunction occurs when Tory's father, the physical abuser whose memory cripples Tory in the present, returns to Progress and becomes the prime suspect in the murder of Hope—and in the later murders linked to it.

These storyline-crossing characters give Roberts a way to weave together Tory's plot layers. Some might find these connections forced. I say they are effective, giving

Carolina Moon

a rich connectedness that makes the novel feel complex and engrossing. Roberts's legions of fans obviously agree.

Count the nodes of conjunction that weave together the layers in your novel. How many are there? Why not search for more? That is what the exercise in chapter fourteen is there to help you do. A tightly woven novel is one that your readers will be able to wrap around themselves luxuriously as they curl up in their favorite chairs with a cup of tea. (They are trying to relax, but you are keeping them tense on every page, right?)

_____________EXERCISE

Weaving Plot Layers Together

Step 1:

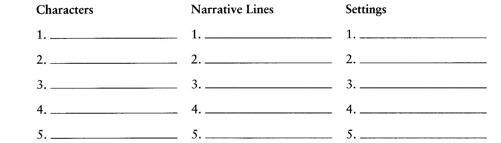

On a single sheet of paper, make three columns. In the first column list your novel's major and secondary characters. In the middle column, list the principle narrative lines: main problem, extra plot layers, subplots, minor narrative threads, questions to be answered in the course of the story, etc. In the right-hand column, list the novel's principle places; i.e., major settings.

Step 2: |

|

Follow-up work: |

|

Conclusion:

Three hundred pages into a manuscript, your story can feel out of control. The elements can swim together in a sea of confusion. This panic is normal. Your novel will come out okay. Trust the process. If you have set a strong central problem, added layers, and found ways to weave them together, then the whole will come together in the end.

Weaving a Story

105

Subplots

P

lot layers are the several narrative lines experienced by a novel's protagonist; subplots are the narrative lines experienced by other characters. What constitutes a narrative line? Problems that require more than one step to resolve; in other words, that grow more complicated.

Now that we've got our terms straight, what is the best way to go: layers or subplots? Today, the term subplot has an almost old-fashioned ring. It makes us think of sprawling sagas of the type written by Victor Hugo and Charles Dickens. Subplots are found throughout twentieth-century literature, of course, and in contemporary novels, too.

Yet what is striking about recent fiction is its intimacy. Authorial and objective third-person points of view have been almost entirely replaced by first-person, and close or intimate third-person points of view. The rich woven texture of breakout-scale novels comes more often from the tight weaving of plot layers than from the broad canvas sprawl of subplots.

But that is not to say that subplots have no place in breakout novels. Far from it. Examples of extensive use of subplots abound on the best-seller lists. Many of the novels discussed in this workbook employ subplots as well as plot layers.

Even Dickensian sprawl can be found. Michel Faber's Victorian morality tale

The Crimson Petal and the White

was, in fact, compared by reviewers to Dickens, and it is true that Faber's narrative voice is intrusive and authorial in the manner of nineteenth-century novelists. He frequently addresses his readers directly, as we see in this early passage in which Faber takes pity on the reader following a long section detailing the introspection of the novel's main character:

So there you have it: the thoughts (somewhat pruned of repetition) of William Rackham as he sits on his bench in St. James Park. If you are bored beyond endurance, I can offer only my promise that there will be fucking in the very near future, not to mention madness, abduction, and violent death.

Well okay, then! Faber goes on to spin out a number of subplots. Rackham is under pressure as his annual stipend is slowly reduced in order to coerce him into assuming directorship of his family's business bottling perfumes and toiletries. Longing for artistic expression but burdened with an invalid wife and child, he seeks release with prostitutes, advised by his jolly friends Bodley and Ashwell and their bible, a slim guidebook called

More Sprees in London.

It is this somewhat inaccurate booklet that brings Rackham to Sugar, a high-priced prostitute of unusual beauty, attentiveness, education, and sexual versatility. Sugar is all that he desires. She is even writing a novel; one, we discover, that is mostly about the mutilation of men.

Sugar herself carries a substantial amount of the story. When first we meet her, she is employed by the sour madam Mrs. Castaway, who may or may not be Sugar's mother. Either because he is rich and easy or because she is won by his genuine affection for her, Sugar agrees to become Rackham's exclusive mistress. She moves into a house that he provides for her.

Meanwhile, Rackham's brother, Henry, a minister, haltingly pursues a charitable widow, Mrs. Emmeline Fox, who runs a Rescue Society for prostitutes. (You can see already that Faber will weave his many subplots together.) Henry's courtship inches forward until consummation, after which, unfortunately, he perishes in a fire in his paper-cluttered cottage.

At the Rackham home, Rackham's bedridden wife, Agnes, preoccupies their dwindling household staff with her hypochondria. She fears she is going mad (and in fact is). She longs for relief and begs Mrs. Fox to direct her to the "convent" where she may find "eternal life." She buries her diaries in the backyard.

Unable to stand being apart from Sugar, Rackham (at Sugar's suggestion) hires her as a nanny to his bed-wetting daughter, Sophie. Sugar enters the Rackham household, but as soon as she does Rackham begins to grow distant. It slowly emerges that Sugar appeals to him as a prostitute, not as a companion. Sugar, in contrast, is drawn to the stability of domestic life. She befriends Sophie with kindness and cures her of her bed-wetting. She digs up Agnes's diaries and reads them, gaining understanding of Agnes's pain.

The climactic events of all these subplots take 200 pages or so to play out. What a saga! Faber's novel in its U.S. hardcover edition clocks in at 834 pages. It's a novel to wander in, and one feels sorry when it is over.

And yet to achieve the tapestry effect of multiple subplots, it is by no means necessary to write at such length. Cecily von Ziegesar's zingy young adult novel

Gossip Girl,

discussed in earlier chapters of this workbook, has just as many subplots but delivers them in a breezy 199 pages. How does she do it?

Gossip Girl

first introduces New York private school girl Blair Waldorf, a too-rich, too-busy, and under-supervised seventeen-year-old who wants to lose her virginity with her boyfriend, Nate Archibald. Her various setbacks away from that goal form the principle plotline in the novel.

The main obstacle to Blair's ambition is her former friend, the stunningly gorgeous but troubled Serena van der Woodsen. Serena's return to New York, her abandonment by her former friends, her failure to fire Nate out of his

ambivalence, her discovery of avant-garde art (a blurred picture of her eye— or maybe her belly button or possibly a more intimate body part—appears in ads all over the city), and her discovery of filmmaking and a more interesting boy than Nate, occupies a significant portion of the remaining novel.

But there are other subplots, too. Serena's love interest, Dan Humphrey, finds Serena, loses her, and finds her again. Student filmmaker Vanessa Abrams has a crush on Dan, but finds a more interesting possibility in a Brooklyn bartender. Dan's little sister, Jenny, worships Serena, volunteers to work on a film Serena never even scripts, and, to be near Serena, she even crashes a charity fundraiser called "Kiss on the Lips" that raises money for Central Park falcons. (Why do falcons need money, you ask? No one really knows.) Meanwhile, preppy lecher Chuck Bass hits on every girl in sight, including Serena, and winds up with Jenny, whom he molests in a ladies' room stall at the "Kiss on the Lips" party.