Writing the Breakout Novel Workbook (37 page)

Read Writing the Breakout Novel Workbook Online

Authors: Donald Maass

Eugenides does not slip us inside anyone's head. He achieves his delineations by sheer force of objective observation, as in this early scene when the narrator attends the one and only party that the sisters are allowed to throw. As "we" (as I mentioned, the narrator speaks for an entire Michigan town) enter the downstairs rec room where the party is underway, "we" realize for the first time that the pretty Lisbon girls are all different people:

We saw at once that Bonnie, who introduced herself now as Bonaventure, had the sallow complexion and sharp nose of a nun. Her eyes watered and she was a foot taller than any of her sisters, mostly because the length of her neck which would one day hang from the end of a rope. Therese Lisbon had a heavier face, the cheeks and eyes of a cow, and she came forward to greet us on two left feet. Mary Lisbon's hair was darker; she had a widow's peak and fuzz above her upper lip that suggested her mother had found her depilatory wax. Lux Lisbon was the only one who accorded with our image of the Lisbon girls. She radiated health and mischief. Her dress fit tightly, and when she came forward to shake our hands, she secretly moved one finger to tickle our palms, giving off at the same time a strange gruff laugh. Cecilia was wearing, as usual, the wedding dress with the short hem. The dress was vintage 1920's. It had sequins on the bust she didn't fill out, and someone, either Cecilia herself or the owner of the used clothing store, had cut off the bottom of the dress with a jagged stroke so that it ended above Cecilia's chafed knees. She sat on a barstool, staring into her punch glass, and the shapeless bag of a dress fell over her. She had colored her lips with red crayon, which gave her face a deranged harlot look, but she acted as though no one were there.

No one is going to mix up the sisters after such sharp, detailed descriptions— especially not Cecelia, who kills herself during the party by throwing herself on the spikes of the fence that surround their yard. Gradually, the narrator's review of later-available evidence, his "interviews" with those who knew the girls, and his close observation of the events of the "year of the suicides" further separates the sisters—and the very different reasons for their deaths.

In a way, you almost cannot pile on too many details that make one character distinct from another. Michael Chabon's third novel,

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay,

which won a Pulitzer Prize, tells the story of two cousins who ride the crest of popularity of comic books before, during, and after World

War II. At the novel's opening, Chabon introduces one of them, Sam Klayman in a passage that piles detail upon detail to bring alive an uniquely Brooklyn adolescent, even before Sam has spoken or done a single thing:

Houdini was a hero to little men, city boys and Jews; Samuel Louis Klayman was all three. He was seventeen when the adventures began: bigmouthed, perhaps not quite as quick on his feet as he liked to imagine, and tending to be, like many optimists, a little excitable. He was not, in any conventional way, handsome. His face was an inverted triangle, brow large, chin pointed, with pouting lips and a blunt, quarrelsome nose. He slouched, and wore clothes badly; he always looked as though he had just been jumped for his lunch money. He went forward in the morning with a hairless cheek of innocence itself, but by noon a clean shave was no more than a memory, a hoboish penumbra on the jaw not quite sufficient to make him look tough. He thought of himself as ugly, but this was because he had never seen his face in repose. He had delivered the

Eagle

for most of 1931 in order to afford a set of dumbbells, which he had hefted every morning for the next eight years until his arms, chest and shoulders were ropy and strong; polio had left him with the legs of a delicate boy. He stood, in his socks, five feet five inches tall. Like all of his friends, he considered it a compliment when somebody called him a wiseass. He possessed an incorrect but fervent understanding of the workings of television, atom power, and antigravity, and harbored the ambition—one of a thousand—of ending his days on the warm sunny beaches of the Great Polar Ocean of Venus. An omnivorous reader with a self-improving streak, cozy with Stevenson, London, and Wells, dutiful about Wolfe, Dreiser, and Passos, idolatrous of S.J. Perelman, his self-improvement regime masked the usual guilty appetite. In his case the covert passion—one of them, at any rate—was for those two-bit argosies of blood and wonder, the pulps. He had tracked down and read every biweekly issue of

The Shadow

going back to 1933, and he was well on his way to amassing complete runs of

The Avenger

and

Doc Savage.

It is as if Chabon filled in several delineation charts and dumped their entire contents into his second paragraph!

How are your characters different from one another? In your mind, I am sure they are all quite different—but how is that specifically conveyed to your readers? Use charts to create separate vocabularies, traits, actions, and more for your characters. You will be surprised how much more individual they become.

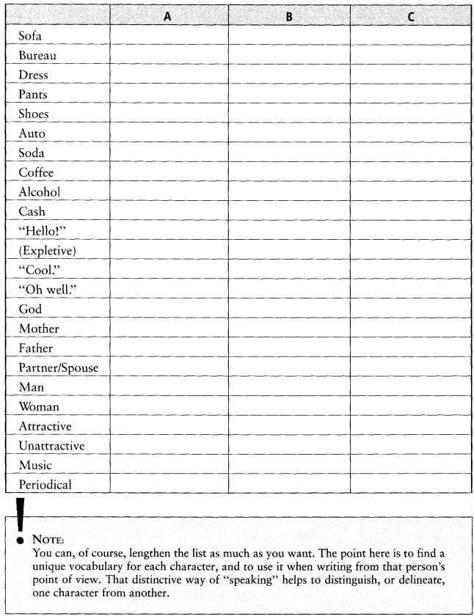

_____________EXERCISE

Improving Character Delineation

Step 1: In the following chart the columns A, B, and C are for different point-of-view characters in your story. (You can add more columns.) For each character, work down the list of common words on the left and

write in the word that character A, B, or C would use instead.

Follow |

|

Conclusion:

Have you ever read a novel in which all the characters talk alike and seem alike? That is weak point-of-view writing. Strong point of view is more than just the words a character uses. It is her whole way of feeling, thinking, speaking, acting, and believing. Each will feed into the point of view. One character's cadence and sentence structures will be different from another's. So will his words, so will his thoughts, so will his actions and reactions. Make your characters different from each other, just as are people in life. That way, your novel will have the variety and resonance of real life, too.

Theme

T

here are so many different ways to discover and develop the themes in your novel. Themes can be motifs, recurring patterns, outlooks, messages, morals—any number of deliberate elements that make your manuscript more than just a story; indeed, that makes it a novel with something to say.

As I discussed in previous chapters, a major secondary character in Mary Alice Monroe's

Skyward

is teenager Brady Simmons. Brady comes from a poor South Carolina low country family. When his father shoots an eagle near the bird of prey rescue clinic that is the focus of the novel's action, Brady takes the rap because the fine will be less for a juvenile. Brady also is sentenced to community service—at the clinic for birds of prey. Angry about everything, he arrives at the clinic vowing to make everyone at this "rehab joint" as miserable as him.

That is not quite how things go. The clinic becomes the vehicle for Brady's salvation. The clinic's head and the novel's protagonist, Harris Henderson, unaware that Brady did not shoot the eagle, grudgingly gives him a chance, but only the slimmest:

Brady's head shot up. "I thought I was going to be working with the birds."

Harris's eyes flashed. He wanted to tell him hell would freeze over before he'd let him touch his birds. He took a moment to rein in his anger at the kid's arrogance before saying in a level voice, "Let's get this understood right from the start. No one gets to care for the birds without approval. Not any volunteer. And you, Brady Simmons, are not a volunteer. You're going to have to work extra long and extra hard to earn that approval from me. We're all here to serve those birds. It's not the other way around." . . .

Brady shot the man a wary glance.

"You'll start by working with a by-product of birds. See that bottled soap over there? And those scrub brushes? And that

hose? Lijah here's going to show you how to use all that stuff along with some of that muscle power you've got to scrub clean every one of those kennels."

Brady is going to clean out the bird's cages—all for a crime he did not commit. This kid's got problems, not the least of which is his attitude. He needs a break. He needs a friend. He needs a girlfriend. He needs a real father. Most of all, he needs self-respect and a new outlook on the world.

Can he get these things? At first Brady doesn't even know he wants them, but soon enough he yearns for change, though the level of his hope is limited. He'll settle for getting by. Finding a friend is beyond his vision. Getting a girl is pretty much out of the question, given his conviction. His father is a hopeless, violent redneck. As for working directly with the birds of prey—that is too much to hope for.

Here's what happens: Elijah Cooper, a wise old

griot

(African-American oral historian) who works at the clinic, patiently takes Brady under his wing. Slowly, Brady begins to change. He does his work without complaint and earns the respect of the other volunteers and, eventually, even of Harris Henderson.

More than friends, he finds supporters and cheerleaders, among them a brainy and beautiful African-American teenager, Clarice Gaillard, who volunteers at the clinic. Clarice warms to Brady, encourages him, and helps him study. Eventually their relationship even gets a bit physical. Brady's opinion of himself changes, his grades improve, and he begins to think about applying to colleges.

Most of all, Brady begins to discover his affinity for the birds, and to understand the relationship between falcons and humans. His transformation begins one day as he watches Harris retrain a convalescing hawk to hunt. Brady thinks it looks easy; that the hawk is following its instincts, nothing more. Also on hand is a resident bird, Risk, who is not on a tether and yet does not fly away. Brady asks Elijah why:

"They

choose

to stay."

When Brady looked back, puzzled, Lijah shook his head. "That's what I mean exactly. Birds of prey ain't the same as the rest of the birds. You can't just train raptors. They ain't like dogs neither. Those animals want to please. Not raptors. They be proud and independent. That being their nature, you can't go demanding obedience from them. Can't do that with a child, neither. All you can do is ask."

Brady listened, feeling the words take root in his heart. At sixteen years old, he'd had enough of people making him jump when they said jump.

"That's why," Lijah concluded, "to work with raptors, you first have to be humble."

"Humble?" he asked, confused.

"That's the truth," Lijah confirmed with a solemn nod. "And

that be a hard, hard lesson for a man to learn. With a raptor, you're never the master. You're the student. You have to learn the ways of the hawk. To learn the spirit of the hawk."

Having learned the lesson of humility, even Harris recognizes that Brady has something special, and offers to train him as a falconer. This is more than Brady ever dreamed he could get, but even better than winning the chance to work with the birds, for Brady, is the winning the respect of Harris: