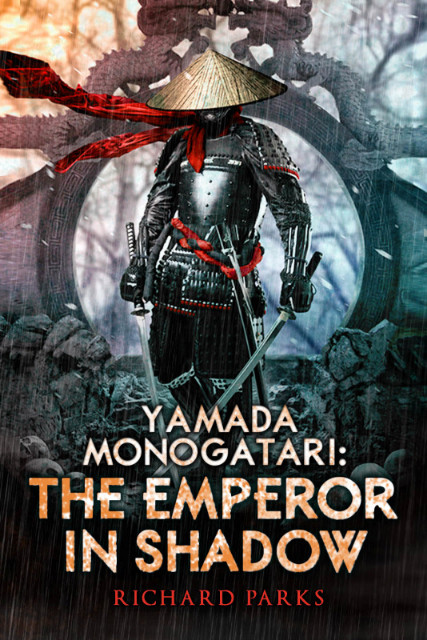

Yamada Monogatori: The Emperor in Shadow

YAMADA MONOGATARI:

THE EMPEROR IN SHADOW

RICHARD PARKS

To the Memory of Fritz Leiber

Copyright © 2016 by Richard Parks.

Cover art by Alegion.

Cover design by Sherin Nicole.

Ebook design by Neil Clarke.

ISBN: 978-1-60701-481-2 (ebook)

ISBN: 978-1-60701-473-7 (trade paperback)

PRIME BOOKS

Germantown, MD

www.prime-books.com

No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means, mechanical, electronic, or otherwise, without first obtaining the permission of the copyright holder.

For more information, contact Prime Books at [email protected].

CHAPTER ONE

“Yamada-sama, this is a waste of time.”

Kenji and I were on our way to the Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Shrine for a festival, albeit Kenji went somewhat reluctantly. Any dealings relating to the Way of the Gods versus the Eight-Fold Path made him uncomfortable, especially considering his position as the abbot of a prominent, although small, local temple. He judged his attendance at a shrine

matsuri

as inappropriate. I considered his habit of flirting with any woman even remotely open to his advances more unseemly, but I knew Kenji’s piety was real, even if it was his own and no one else’s.

“A

youkai

has been reported in the vicinity, and I was asked to investigate. Since I may need your help, I asked you to attend. Are you afraid someone will see you?”

“I should ask you the same,” he replied dryly. “Great Lord Yamada, wandering through a festival crowd like some unwashed farmer? Besides, Hachimangu is the Minamoto clan shrine. Let them see to its security.”

“They did. Lord Yoriyoshi was the one who requested I investigate, and it was under his authority I brought you along.”

“Oh.”

This fact altered Kenji’s attitude considerably. We were present at the request of the chief of the Seiwa Genji. I hadn’t informed Kenji ahead of time. I expected grumbling—and was not disappointed—but I knew he would come along, and so it proved. I also hadn’t told him I had resolved to investigate the shrine even before Lord Yoriyoshi’s command.

Unlike Kenji, over the years I had become rather fond of

matsuri

, and the possible

youkai

was just a convenient excuse. Assuming, of course, the

youkai

was only a rumor. If it were real, this would be an entirely different situation. All

youkai

were monsters, but not all monsters were the same. Some

youkai

were frightening but harmless, some merely annoying, and some were deadly in the extreme. It was my responsibility to discover the true situation at the shrine and Kenji’s to assist me, however he might feel about frivolous shrine festivals.

We walked through the crowd. Everyone was wearing their best clothes except for Kenji and me. I was trying to avoid attention, and Kenji wore the robes of a common priest almost out of habit. As it was, he drew more glances than I did, simply by his presence at a shrine festival. He ignored them, but I realized there was another dimension to his discomfort I hadn’t previously considered.

“So you really are afraid someone will see you. I was merely joking before. You know shrine and temple functions are combined here, as elsewhere. It’s not as if they’ve never seen a priest of your order.”

Kenji scowled. “Exactly, and it’s a temple to which I feel a certain rivalry, if you will. If one of the shrine or temple priests recognizes me, I’ll never hear the end of it.”

I hid a smile. “We’ll try to avoid them—”

I stopped, but Kenji already had a ward in his hand. “You felt it, too,” he said.

“Something . . . ” I wasn’t quite as sensitive as Kenji, but the presence of a

youkai

did tend to make my skin prickle, and I had learned not to ignore the sensation. “That way, I think.”

We made our way through the crowd as quickly as we could without knocking anyone down. We crossed the main avenue leading to the shrine, past the bright red torii gate just in time to see what appeared to be a young woman dressed as a shrine dancer disappear into the trees lining the avenue.

“She’s the one,” Kenji said. “I’m sure of it, but I don’t know what she is.”

“Then we’d better follow and find out.”

“You do have your dagger concealed in your sleeve, yes?” Kenji asked.

“Always.”

“Good. By the time I know what we’re dealing with, it may be too late to find the right ward. If that happens, I trust you will keep the creature occupied until I find it.”

“You’d better hope I can do so, if it comes to it,” I said. I kept my voice low, as we were already slipping through the maple trees lining the main approach to the shrine. Soon we were into deeper woods, which had been left untouched by the construction of the shrine less than five years before. While the Hachimangu had its

kami

in residence, the forest itself was much older and likely to have its own gods, not to mention other residents might not be favorably disposed toward human beings. We went with caution, but the waning moon was a week past full, and its light cast more shadows than it illuminated.

There was a patch of red less than a bowshot away from us, which I realized was the

hakama

of the dancer, caught for the briefest moment in the moonlight.

“This way,” I said, and Kenji fell in behind me.

“It really would help,” he said, fumbling with a handful of spirit wards, “if I knew what sort of creature we were dealing with before we catch up to her. Are you sure you have no impression of her?”

“An educated guess only and not to be relied upon. Perhaps you would prefer our quarry to appear before us and humbly introduce herself?”

“Actually, this would be helpful,” Kenji said. “Since that courtesy is not going to happen, I suggest we keep our voices down and our wits about us.”

That was reasonable. Until we knew what was waiting for us in the woods around Hachimangu, my casual attitude so far had been more than reckless. I resolved to move more carefully, listening to the sounds of the night around us, and, for a bit, I spoke not at all. Kenji, did the same, but it was not in the priest’s nature to be silent for long; he was the first to break the silence.

“So, what is your guess?” he whispered. “You never said.”

“Because I’d rather not. If you or I put too much faith in speculation, it could get us both killed. I would not like that.”

Kenji sighed. “Fair enough . . . I think we’re getting closer.”

It wasn’t so much that Kenji and I were making good progress through the trees but rather that our quarry had stopped moving. We emerged into a small clearing and there she stood, her back against an ancient

kusunoki

fifteen paces around the trunk. It was the largest camphor tree I had ever seen.

My first glimpse of her was confirmed now. She wore the clothing of a temple dancer and appeared to be about sixteen, but even from across the clearing, no more than thirty paces or so, I could see the darkness in her eyes and understood she was much, much older.

Kenji glanced at the figure, then again at his wards. “I still don’t—”

“Put them away, Kenji, unless you want us to risk being cursed. They aren’t needed.”

Kenji frowned, looking at the girl and the tree. “A

kodama

?”

“That was my guess. In this forest, it did seem likely.”

Kodama

were generally harmless, provided you didn’t attack them or try to cut down the tree, which in essence was the

kodama

itself. There was some debate among scholars as to whether a

kodama

was merely a spirit of the forest or an actual

kami

, a forest god. Whatever their true nature, they were powerful but generally minded their own business, except for this one who appeared and attended a shrine festival in human form. That was something unusual. I would have spoken to her then, but it was clear she wanted nothing to do with us. In another moment she stepped back, the tree enfolded itself around her, and she was gone.

“Let’s go to the shrine,” I said, and Kenji fell in behind me.

“Why do you think she took human form?” Kenji asked.

“Curiosity, perhaps. Or . . . ”

Kenji grinned. “Say it.”

It was my turn to sigh. “Fine. Perhaps she was meeting a human lover. It has been known to happen. But she’s no threat to anyone. Except, perhaps, her paramour, if he treats her badly. If I knew who he was, I would advise him to tread lightly. Or not. One can only make one’s own mistakes in matters of the heart. I know.”

Kenji scoffed. “And you think I’m a romantic.”

“No, I think you’re a reprobate priest—pardon me, abbot—who shows far too much interest in the pleasures of this world.”

Kenji grunted. “Just so. I fear you’re the romantic one, Lord Yamada. In your own strange fashion.”

Perhaps Kenji had been right about that, once, years ago. Princess Teiko took those notions with her to the grave, and I had not been burdened with them since . . . mostly.

We emerged into the broad pathway leading up to Hachimangu and were once more on the edge of the shrine festival crowd. Evening was falling now and bright red and yellow paper lanterns hung from posts and the trees scattered through the grounds.

“Has our obligation to Lord Yoriyoshi been discharged?” Kenji asked.

“It’s possible there are other

youkai

about, but it seems more likely the

kodama

’s presence within the shrine boundaries is responsible for the rumors. It would certainly explain why no one had been harmed. I’ll send word to Yoriyoshi-sama.”

“Good. Now, if you’ll pardon me, there is a situation I must attend to personally.”

I smiled. “Who is she?”

I didn’t need the slight flush creeping up from his cheeks to his badly shaven head to tell me I’d judged correctly.

“Lord Yamada, really . . . ”

“It’s not my fault you are so predictable. Yet I will respect the lady’s privacy, even if I sometimes invade yours.”

Kenji spared me a glance of annoyance. “I live for the day your heart returns to you, Lord Yamada. I promise to gloat for no more than a year, possibly two.” With that he turned into the crowd and was soon out of sight.

I stood there, leaning against one of the lantern poles as I watched the festival crowd. I had often wondered why the sight, sound, and smells of a shrine festival attracted me so, and in that moment, triggered by something Kenji had said, I began to see a glimmer of an explanation. Festivals were happy events, with men and women and children all out and enjoying themselves. I had known happiness myself. Once with Princess Teiko, and then again when my adopted daughter Mai was married and presented me with my first grandchild. But now Mai and little Akiko were with Mai’s husband at his post as the newly appointed Governor of Tosa, far to the southwest. As for my adopted son Taro, he was leading a delegation to buy horses in Mino and wouldn’t be back for weeks. At once I was both proud of them and yet sad they were not with me, and in Mai’s case likely never would be again. Having not so long ago been reminded of what it was like to have a family, now I was being equally reminded of what it felt like to lose one. Festivals helped me remember what it looked and felt like to be happy.