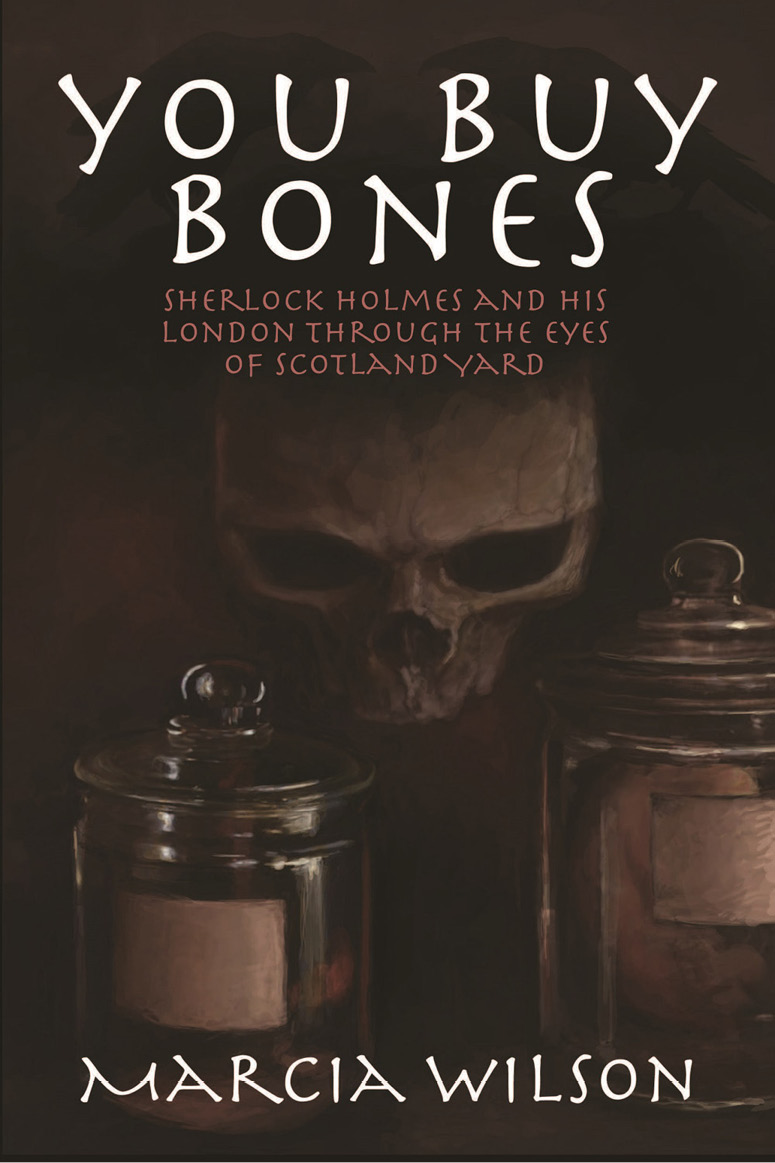

You Buy Bones

Authors: Marcia Wilson

Tags: #Sherlock Holmes, #mystery, #crime, #british crime, #sherlock holmes novels, #sherlock holmes fiction

Title Page

YOU BUY BONES

Sherlock Holmes and his London Through the Eyes of Scotland Yard

Marcia Wilson

Publisher Information

First edition published in 2015 by MX Publishing

335 Princess Park Manor, Royal Drive, London, N11 3GX

Digital edition converted and distributed by

Andrews UK Limited 2015

© Copyright 2015 Marcia Wilson

The right of Marcia Wilson to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1998.

All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without express prior written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted except with express prior written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1956 (as amended). Any person who commits any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damage.

All characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and not of MX Publishing.

Cover layout and construction by

www.staunch.com

Prelude

Somewhere on the Cornish Coast

The two men huddling around the lonely camp-fire against the gloom were similar in height and build if years apart in age. In a particular-ness of dress and demeanor they might have been father and son within the demands of their duties - if the father had lived much harder than the son. Tonight they were united in the garb of common labourers in threadbare greatcoats over slops,

[1]

grey-blue shirts over corduroy trousers tied at the ankles with packing twine, and coarse cowhide boots better fit for trapping the cold against the foot than keeping it warm. Fitting to their temporary identities, they were no credit to the nose.

“Is it supposed to have those green bits?”

The elder never looked up from stirring the

coals about the cooking-trivet that had begun its life long ago as an iron

waggon-wheel. “Those “green bits” are leaf celery and beetroot-tops.” He

tapped the pot with his stick; sparks showered up.

“You should remember, Hopkins,” he said pointedly with a flash of those

too-dark eyes. âYou helped pinch them this morning.”

Stanley Hopkins (also a Yarder but far from being as long in the tooth

as his supper companion) didn't want to remember. The

theft was from a long-abandoned garden but it was still

someone's

private

land and policemen - even policemen out of twig

[2]

were really supposed to

be above that sort of thing.

Still, all other considerations failed at the sight of what Lestrade had

(with apparent optimism), termed

supper

. He couldn't positively identify

what their oven had once been, but it was never meant for culinary

practicality. It was thin cast-iron; he saw that much. Lestrade had

arranged the tinfoil-wrapped vegetables in the bed of coals and covered

them with ash; after that, the mysterious round metal sheet, and on top,

the small cooking-pot. There was something about it that made the young

man think of the Great Western Railway. He hoped he was wrong... but he doubted it.

Night crept over Cornwall from behind. Despite the gloom lurking in

the celestial backdrop, Hopkins found his attention increasingly drawn to

the soft smears of colour tinting the delicate line between ocean and

the sky. It was a compelling view and better than the jumbled lumps of

dank stone remains across the lonely moor at their backs. They reminded

him of alleyway thugs, drunkenly lurching their way to an even drunker victim. Hopkins didn't like the old Neolithic huts at first

chalk; with the fading of the day, the place was even worse. Nightmarish.

Positively gruesome and disturbing and...

threatening

in ways the London rookeries weren't.

He wasn't superstitious; he didn't believe in ghosts, but Hopkins could well

believe the land had forgotten to tell the residents that the Ages had

moved on without them. Images of wild savages in skins with murderous

spears were leaking into the young man's brain. Ghosts would be

preferable.

“Hopkins, you've been jittery all day. You've been in

disguise before; what is it?”

Hopkins breathed out, grateful that Lestrade only looked puzzled and

concerned rather than impatient. “I suppose part of it's because I haven't

been out in the open in a few years,” he began slowly. “But also, it's quite

an ugly case we're on! When was the last time the Home Office had to

pull in so many different Inspectors and Sergeants for a single job?”

“1891.” Lestrade answered promptly. “Twelve Inspectors, three

sergeants, and I believe the total of PCs and Chief Constables came to... 39.

I might be wrong about that one... did Bow Street use both of the Irish

Twins, or just one?”

“Who's to know?” Hopkins wondered, and for the first time that

evening, the two men laughed. Humour in the face of a crawling wet mist

wasn't an easy thing to come by. “You're thinking of the Docks Case,”

Hopkins mused. “Lord, what a mess that was.” He sighed and touched

his leg with a sudden mischievous expression. “My first true battle-scars.”

“Dear me. I couldn't tell you how many I picked up on that one,”

Lestrade grimaced. “I think I lost count after they stuffed me into that

barrel. Some of the details are a blur.”

Hopkins shuddered. “I don't mind telling you, I never regret the

conclusion of a case, but there are times when we're working on one that

I fear we aren't doing any good.”

“Get used to that.” Lestrade gave the pot a

tap. More sparks took wing. “Right. Just a bit longer and we'll have supper... the Great Way Round.” (This sadly confirmed Hopkins' reluctant identification as to the scrap metal cookery).

[3]

“I suppose what really makes it hard for me is the knowing there're

so

many

deaths on this case already.” Hopkins sighed and stuffed his hands

into the deep pockets of his rag-shop slops. The man he was

impersonating had been of the unwashed sort and Lestrade had said

bluntly there was no need to don his

exact

clothing unless they were likely

to be smelt from the ocean - not when he had to work with him, thank

you. “Fourteen poor tinners

[4]

murdered... all for being in the wrong place

in the wrong time. Who would bother killing

miners

, I ask you? Their lifespan

is chancy enough!”

“You're asking the wrong person. Relics and professional degrees mean

this

-!” Lestrade snapped his fingers; it made a cracking sound across the

plain, “-against a man's life. I don't care how many years are spent in

their education, how many strings they had to pull, favours to cull,

patrons to worry. Bone-hunters are a queer lot. They're not murdering

each other for

survival

; they're murdering for their

reputation

.” Lestrade

finished by tapping his forehead to indicate insanity. “When it comes

to the landed folk, I swear to you, the lot's barmy as the Queensbury's Third Marquis.”

Hopkins shuddered. The cannibal Marquis was not a nice image

for one who was all but alone, in unfamiliar territory, with equally

unfamiliar nourishment... in front of a cook-fire no less. “Reputation... It's a

small thing in the whole scheme.” He said thoughtfully. “Too small to be

worth triggering a mine's collapse so you don't have to pay some hungry

miners a few bob for helping you smuggle out Stone Age treasures!” A part of him was still sour because this was all doomed to wrack and ruin, and they had only been called in because the local police might be lynched if they dared bring the local perpetrators to justice.

“It

is

a small thing.” the older Yarder agreed as he threw in a lump of

soft-coal he'd harvested at the shoreline. Sparks fountained into the night. Wisps of oily smoke curled up

around the edges and Lestrade wiped his hand fastidiously on the damp

grass. Bituminous was like that; it put a layer of grime on you before and

after it was burnt. “You'd be surprised how many people have been

murdered here, Hopkins. Not just for silly potsherds and stone bits and

pretty stones. I would say this has been going on since before the

Romans.”

“How can you be so sure?” Hopkins wondered, more curious than

challenging. That was his great strength although he wasn't aware of it.

His burning need to know touched the hardened oldsters at the

Yard - even the Bow Street crowd, who remembered something of their

young selves in the newcomer. “There's not that many records after the

Romans left, and most of those are mouldering church records.”

Lestrade merely shrugged. “First of all,” he began, drawing orange letters in the

air with the glowing end of his stick: ONE. “This is

Cornwall

. People have

been mining it since they found out about bronze. Tin was valued, so

naturally no one was just going to up and tell the powerful trading partners

across the seas where they were and how they were doing. If

your teachers were anything as brutal as mine, they would have mentioned

something about the role of tin in the Roman Invasion.” He shrugged.

“The Greeks believed in a mythical Cassiterides - Tin Islands - west of

Europe, so this place is as good as any to be a point of mythological

misdirection.”

Hopkins made a musing sound and picked up his tiny teapot. “I remember my teachers saying the Tin Islands had to exist somewhere in the ocean, or they wouldn't be called

islands

.”

“Academics.” Lestrade scoffed. “No comparison to honest work. Islands

also

mean lumps of earth that rise up... I learnt that from a

real

teacher, name of Mortimer.

[5]

A tin seam

is

an island, Hopkins. Mines are just the means to extract the stuff hiding in the ground. And as long as there's something worth having, the neighbour sees it as something worth getting.” He took his own cup and knocked half the portion down. “Been that way a long, long time.”

Hopkins was thinking back. “Most people don't refer to the Romans as invaders,” he pointed out. “More like improvers. Saviours of culture and all that.” He stopped talking as Lestrade's too-dark eyes sank into his chest, threatening to rip the heart-roots right out of the ribs.

But the little man only smiled; his sharp, swarthy Briton features bent in that way that Hopkins never - quite - accepted without a little shiver. “So they don't. I tend to forget some small details from time to time...” His lignite-coloured eyes reflected the fire-light. Lestrade's mark had been a man close to his size and colouring... but with a sense of dress best described as Gipsyish. A loose rag draped about his neck the same bright blue as the patches at his elbows. From across the flames, Hopkins thought his normally fastidious officer-in-charge looked like one of the little Tinkers they were frequently running off Hyde Park. The small man's uncombed hair and grease-smeared face only added to the sense of an altered reality.

Hopkins sighed and held out his battered tin bowl with good grace. Lestrade dropped a ladleful of smoking broth inside. At least he could identify the bacon - he had brought it along. The rest was a mangel-wurzel

[6]

of admirable size. Lestrade had briskly alleviated the abandoned garden of its presence, briskly trimming it for the pot and burying the incriminating evidence with a casual skill that still worried his companion.

“How much longer until time?” Now that the sunset had vanished in the western gloom, Hopkins was beginning to stir with the restless worry of doing his job.

“Just a moment...” Lestrade fished in the folds of ragged scarf and pulled out an iron chain. “Where'd that blessed Pole Star get to?” He muttered to himself.

Hopkins grinned; it was most unlikely the Axis had gone anywhere. He watched as Lestrade set the tiny nocturnal dial on the month, and eyed the little metal disk until it lined up with Polaris. Unlike the fixed arm of a sundial, a star dial had to move. Lestrade adjusted it until the arm lined up with the uppermost star of the Big Dipper. “Half-hour.” He pronounced, and popped the dial back around his neck.

“Half an hour's all my nerves have left.” Hopkins muttered.

“You'll do fine.” Lestrade was drinking the broth out of his bowl first. “Granted, I'm sure you'd have more of an exciting time with Mr. Holmes right now, but let's stick to the plan, shall we?”

“I doubt Mr. Holmes wants to see much of me anyway.” Hopkins grunted.

Lestrade only laughed. “You're in a large club, Hopkins. The Holmes Club. No weekly fees required. Don't let it worry you.”

“Things were fine for a long time, and then I made those mistakes.” Hopkins persisted. “It was like... I'd disappointed him beyond measure.” The hurt still echoed a bit, despite his shame.

Lestrade lifted his eyebrows. “He's not like us, Hopkins. He's not one of us. Don't think of him as anything less than an amateur. I know that seems like it's an insult, but

we're

the professionals. We take the lumps and we take the blame for a bad job. Mr. Holmes is a private detective because he's good at what he does, and he doesn't have to follow our rules.” He shook his head. “We can't be like him. He doesn't work all the way within the law and that's not something we can just

do

.” Lestrade freshened his tea. “Professionals are career-men; amateurs are in for it because they love their craft. He can pick and choose his cases; we can't. There's a world of difference between the two and we can't imitate his daft ways of solving cases.”

“I know,” Hopkins admitted. “And I understand that. But I swear to you, every time I work with him, we have to... re-affirm some rule of behaviour.”

Lestrade barked. “Too true! You should have seen him before Watson. The doctor is a calming sort.” He laughed again at the expression on the other's face. “Just because Watson can shoot the eye out of a bloody crow at a hundred yards and is usually the first one to hit the scene of an attack doesn't mean he's not a stable sort. I'll trust his gun any day; Mr. Holmes rarely if ever touches the things, which is just as well. Everyone needs some sort of limitation.” He started into his dinner with hasty enthusiasm, dunking it with some of the rock-hard bread the miners kept in their pockets. “As hard as he is on you, Hopkins, he's even harder on himself. He's a smart one, and that's true. But there's no room in his life for error. That in itself leads to error. Do you understand what I'm saying?”

Hopkins sighed. “Which is why we're out in the centre of nowhere, waiting to catch coded signals from a half-witted gang of academic murderers whilst Mr. Holmes traps the ringleaders in the village?”