Authors: Vanessa Williams,Helen Williams

You Have No Idea: A Famous Daughter, Her No-Nonsense Mother, and How They Survived Pageants, Hollywood, Love, Loss (12 page)

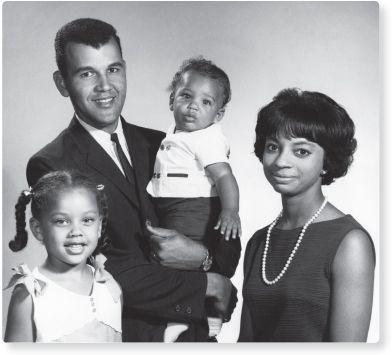

My parents never argued in front of us. If there was a disagreement or some tension, they’d tell Chris and me to go outside and play on the swings or in the sandbox. But this rarely ever happened. Usually when it did, it was Mom who was upset and she’d go in her bedroom and close the door. It was never dramatic. She’d just disappear and my father would go talk to her and all would be resolved. There were never big screaming fits. I grew up in a very calm, Zen-like household.

My mom will say my dad is the only person who could have put up with her. She knows she’s a lot to handle, and she enjoys it. It’s not like she’s unaware of her strengths. If my dad’s Danny Kaye, my mom’s Joan Collins. She loves drama. She loves to be the center of attention. My mother is a spitfire, and she tells it like it is—she doesn’t sugarcoat the truth. Ever.

When I was about eight and riding the bus home from Westorchard Elementary, a girl and her brother called me “nigger” to my face. I had no idea what the word meant, but I knew it was ugly because they had said it with such venom. When I got home, I told my mother what had happened and then asked, “What does that mean?”

I’m sure this was a moment my mother knew would one day come. She’d battled racism her entire life. “There are some people who have a problem with the color of our skin, so you’re going to have to be better than everybody else to be accepted as an equal.”

When I think back to that incident, I’d have to say that the words my mother spoke to me had much more of an impact than what those kids on the bus said. This was the moment it dawned on me that I was different.

HELEN ON RACISM

I knew someday Vanessa would be called that word. I didn’t want her to have a prepared expectation of it. I didn’t want her to go around feeling different. However,

I

wanted to be prepared, so I always knew what I’d say when it happened. I didn’t want to stutter and stammer. I wanted her to understand that being called a name doesn’t make you what that name signifies. It doesn’t define you, but it does define the person saying it to you.

I had felt so safe, so accepted; I didn’t focus on or really even notice my differences. Even at school, when I got older and a kid would tell a racist joke, they’d preface it by saying, “We can say this in front of you because you don’t act black.”

Huh?

I wouldn’t say anything, but I would think,

What does that mean?

I didn’t know what being black meant. My family was the only black family on my street. I was the only black kid in my class, and my brother was the only black kid in his. My mom understood what this meant in a way I couldn’t. Despite growing up in an idyllic suburban neighborhood with our perfectly manicured lawns, we weren’t immune to racism, Mom knew. And even though I felt I fit in perfectly, I was different.

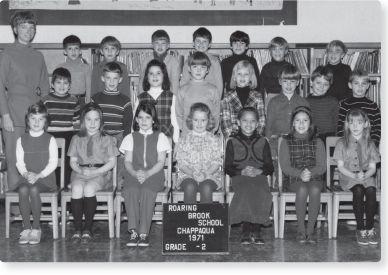

I wasn’t the only person of color in my class—there was Jacob, the Indian kid. But I’ve been told that I was the first black student to matriculate from kindergarten through twelfth grade in the Chappaqua School District. My mom would tell me that at parent-teacher conferences she could immediately spot my self-portrait because it would be the only one with dark skin.

In second grade, I was heading to assembly with my class when some kids said to me, “Is that your sister?”

They pointed to the third-grade class lined up across the hall from us. In their midst was a little black girl I’d never seen at the school before.

She must be new,

I thought.

“No, that’s not my sister. I don’t even know her.”

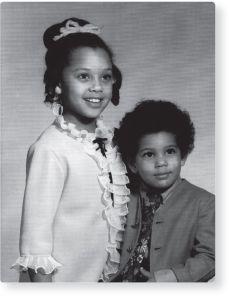

But I desperately wanted to know her! A few days later, I was shopping at the A&P, a grocery store in Millwood, with Chris and my mom. There was the girl!

“That’s her,” I whispered to my mom. “That’s the new girl at my school!”

Mom talked to her mom, exchanged phone numbers, and the rest is history—we became inseparable. Toni lived in Chappaqua, which was too far for me to walk or ride my bike from my house, although I did it once and my mom drove me and my bike home. So I was always begging Mom to drive me to her house, or she was begging her mom to drive her to mine. We played for hours and hours. We’d have tea parties and dress up in her mom’s elegant clothes. We’d set out to explore the woods behind my house or the wetlands behind hers.

We also played with our matching Sasha dolls, the first brown-skinned doll I owned. Toni had a collection of Sasha dolls, and when I saw them, I knew I had to have one, too. Sasha had big brown eyes and came dressed in a brown corduroy jumper over a white Peter Pan–collared shirt. Unlike most dolls that had stiff, wiry hair, Sasha had long, manageable hair. Toni and I would braid and twist and comb her hair all day long. That doll meant so much to me that when I was choosing names for my youngest daughter, I picked Sasha. And I asked Toni to be her godmother.

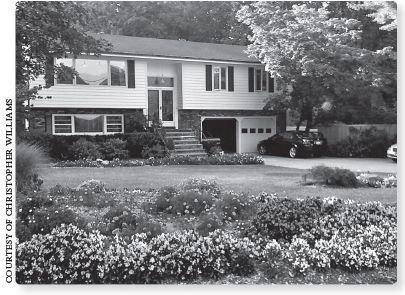

When my parents had decided to move out of their Bronx apartment and into a house in Westchester, they circled an area between their teaching jobs—Mom in Ossining and Dad in Elmsford. They settled on New Castle, a hamlet in upper Westchester that comprised Chappaqua and Millwood. Millwood, a working-class suburb, was more affordable. It was a quaint little village with a few shops, a supermarket, a church, and a gas station. Everybody knew everybody else. No one locked their front doors and the kids roamed freely until bells were rung or voices called them in for dinner. Most of the dads worked in town or near town, while the moms stayed home, taking care of the little ones and watching the older ones get on and off the school bus.

On weekends my parents drove around the area finding homes

for sale. One day they stumbled on a three-bedroom raised ranch house. It wasn’t exactly what they were looking for—but they couldn’t resist the allure of the two-acre property. They put in an offer of $32,000. A week later they found out their offer was accepted.

That’s when some of the neighbors began making a stink. One family spread a rumor that my parents couldn’t obtain a mortgage. This neighbor even called the seller and pretended to represent the mortgage company. Another homeowner suggested a few residents pool their resources and buy the house to insure no “blacks” moved in. But the seller, who lived across the street and had built his house and our house, wanted my parents to buy it.

Growing up, I didn’t know any of this. I played flashlight tag and hide-and-seek with some of the children whose parents didn’t want us moving in. My father lent tools and helped repair cars, plumbing, and appliances for some of the neighbors who had originally opposed the idea of him. No one could resist my dad. He became everyone’s favorite neighbor and adviser. Sometimes it drove my mother crazy. “Who’s he talking to now?” she’d hiss. I think she always felt my dad was being taken advantage of, but he did it all out of the goodness of his heart. As a little girl, I thought he was the smartest guy in the neighborhood.

Besides being the only black family on the street, my mom was one of the few mothers who worked. So she really didn’t have much in common with the stay-at-home moms in the neighborhood. She taught music at Claremont, a public elementary school in Ossining, gave private lessons at our house, and played piano and organ for Saint Theresa’s, our local parish.

One of my favorite childhood memories is of going to weddings with my mother. I’d sit in Mom’s bathroom and study her as she did her makeup before we’d head to church. Mom always applied the same latte-colored foundation. Then she’d dab powder on her face. She wore her lipstick down to this little perfect nub. Then she’d put all her makeup in a small snap bag. Sometimes she’d put her hair

back with an Afro puff at the top. When I was little, Mom would wash my hair, then she’d sit me by the stove, take a comb, and put it on the burner to get it hot. She’d coat my hair with Afro Sheen, the hair relaxer, and comb it straight.

I loved watching Mom play at weddings. I’d sit on the bench next to her and turn the pages of her sheet music while she played traditional wedding songs on the organ. I realized that a wedding was about many things—the flowers, the gowns, the kiss, the couple, love—but Mom’s music brought it to life.

My parents wanted me to love music and dance as much as they did. So while I was in nursery school my mother enrolled me in beginner ballet classes at the community center. I wore a pink leotard and matching tights as I learned the five positions. After a few classes, the instructor told my mother that I was really talented and suggested I take more challenging classes. Mom enrolled me at the Steffi Nossen School of Dance (where I continued studying through high school). I can still remember my mother beaming as she watched me through the glass partitions. I was so happy to know she was looking at me. I wanted to be as talented as my mother. I was in awe of my mother’s talents. I was in awe of my mother.

But I really didn’t know who she was.

The family that plays together, stays together.

Our family home in Millwood, New York

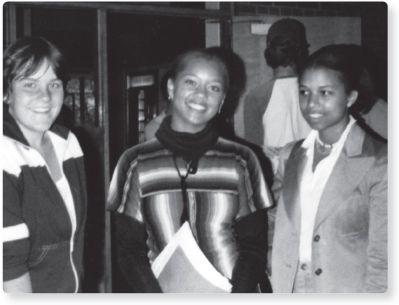

Maura, me, and Toni