You Majored in What? (4 page)

Read You Majored in What? Online

Authors: Katharine Brooks

Not all those who wander are lost.

—J.R.R. TOLKIEN,

THE LORD OF THE RINGS

W

hen you think about the future, do you sometimes feel

Overwhelmed?

Clueless?

Stuck?

Join the crowd. If you’re like most college students or recent grads, you’ve done a lot of different things in your life and sometimes it’s hard to know where and how to direct your focus. After all, you certainly don’t want to miss anything. But the chaos created by so many choices can leave you feeling like a pinwheel: spinning in the wind and going nowhere fast.

• What if you had a way to organize your past so that you could more clearly see your future?

• What if you could discover new empowering information about yourself?

• What if there was a simple way to help you identify what makes you special and interesting to employers?

You’re one blank piece of paper away.

You already learned from the explanation of chaos theory in Chapter 1 that there is always order despite the chaos. You just have to step away from it to see it. The exercise you’re about to complete will help you uncover the most important factors in your life so far, and then give you the priceless opportunity to step away from them, look at them from above, and see the connections.

In this chapter, you’re going to make a Wandering Map: a simple, yet surprisingly powerful tool for organizing the chaos of your life. It won’t serve as a literal map, of course, but it will help you focus on your strengths, identify significant themes and moments in your life, and maybe even start you on a future path. The Wandering Map will help you develop your reflective thinking skills as you look to your past to find your future.

MAKING SENSE OF THE CHAOS

Have you ever noticed that the knowledge you acquire in one area of your life can be applied to a completely different setting? You may have already seen that in your classes—how what you study in one class seems to dovetail with what you’re learning in another. For instance, you might be studying the behavior and culture of a tribe in anthropology class only to find that the way you’re analyzing the tribe could apply to what you’re learning in your business class about behavior in a corporation. Your business professor might not ever mention the words “culture” or “anthropology” but you see the connections. When we take what we learn in one sphere of our life and apply it to another, our knowledge and understanding increase substantially and we open the door for creative thinking and brilliant new insights and ideas.

Nobel Laureate Dr. Herbert Simon, who developed the field of artificial intelligence, discovered the same thing. His degrees in economics, computer science, and psychology gave him the unique vision to see what others had missed. He used the phrase “network of possible wanderings” to describe the value of multidisciplinary perspectives. He said that the more you know about different disciplines and are able see the connections between those disciplines, the more you are able to create innovative solutions to problems. Your mind is able to wander into many territories. Your knowledge of chemistry, for example, might improve your thinking in the field of biology. Or your understanding of poetry might make you a better therapist.

Charles Munger, vice chairman of Berkshire Hathaway and business partner of Warren Buffet, the richest man in the world, calls this approach to thinking “mental latticework” and applies it to investing. He believes that to fully understand the stock market and investments, you need to apply knowledge from disparate fields, including philosophy, physics, psychology, history, economics, biology, and literature. He states that only by understanding the key elements of each of these fields and then pulling them together into a cohesive latticework can one develop what he calls “worldly wisdom,” an invaluable means of making intelligent decisions.

The Wandering Map you’re about to create combines the thinking behind Herbert Simon’s network of possible wanderings, the basic principles of chaos theory, Munger’s latticework, and the visual mapping work of Joseph Novak and Tony Buzan. You’d probably rather get started on the map than read a lot of research, but if you’d like to learn more about these ideas, see the References and Resources section at the end of the book. To put it succinctly, the power and value of the Wandering Map lies in its ability to help you

• brainstorm new ways of viewing and understanding your past;

• identify previously hidden themes and threads in your life;

• break away from linear thinking to look for creative connections;

• make meaningful order of the chaos;

• create a powerful vision for planning your future; and

• get excited about your talents, interests, and possible future.

So I have one question for you:

Is it worth thirty minutes of your time and a blank piece of paper to rise above the chaos and find direction?

Self-discovery requires time and focus. You can’t think clearly in the midst of cell phones ringing, e-mail arriving, friends dropping in, worrying about exams, and so on. So to get the most out of this exercise set aside some time when you won’t be interrupted—thirty minutes is great. If possible, leave your room and go to the library or a park or your local coffeehouse—anywhere you won’t be disturbed. Let’s get started.

SHOW ME THE CHAOS: CREATING YOUR WANDERING MAP

Let’s start by getting your brain ready to create this map. This exercise may seem unusual to you, particularly if you’re more comfortable making lists or writing outlines. It may even seem kind of silly. Trust me: the students who complain the most at first usually tell me it turns out to be the most valuable activity they have ever tried. So suspend your judgment for a few minutes and give it a try. Keep the following thoughts in mind as you create your Wandering Map:

• It will always be a work in progress. You may add items to it anytime you want and we will revisit it in future chapters.

• There are no rules, so don’t sabotage yourself by creating arbitrary rules, such as

• “I must figure out the answer to all my questions.”

• “I must know by two o’clock this afternoon what I plan to do when I graduate.”

• “I must make the perfect map that includes absolutely everything that’s important.”

• “I have to be some kind of artist to create this map.”

• “I should include _________ because my parents think it’s important.”

So unburdened by rules and perfectionist thinking, here we go . . .

First,

get a big sheet of blank paper and something to write with. Poster board or newsprint paper (available in the art section of your college bookstore) or 11 × 17 inch paper is ideal, but you can also work with a regular piece of plain 8½ × 11 inch paper if you wish. Try to avoid using paper with lines because that will increase your tendency to list and organize. We’re working with chaos here, remember. You can use pencils or pens, but I find that people get really creative when they use crayons or colored markers. Something about the bright colors and the fun of using crayons opens up your mind to all kinds of new ideas. It’s more fun if you like the materials you’re using.

Second,

start thinking about all the interesting and significant things you’ve done or have happened to you. Go back as far in your life as you wish. If a significant event occurred at age five, include it. Have you had unique jobs or taken unusual classes? Did you have a memorable summer experience? What are you most proud of in your life? Do you have hobbies you’ve pursued for a while? What awards or honors have you received during your life? Can you think of a particularly valuable lesson you’ve learned? What knowledge do you rely on that you have developed from your experiences or education? What successful experiences can you recall?

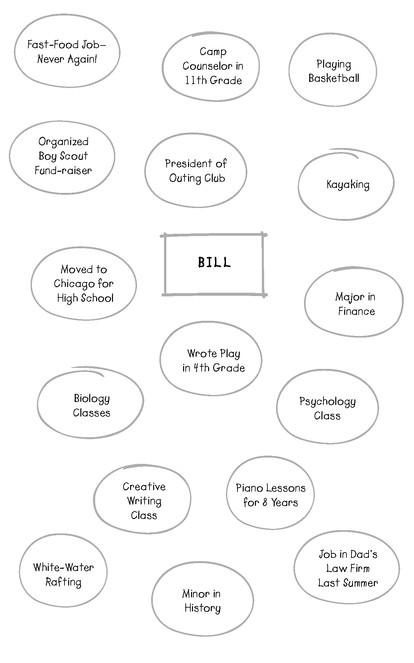

To help you visualize a Wandering Map, there’s a sample created by Bill on page 24, a senior majoring in finance. You can copy the style of map he created or develop your own. Add any shapes or colors or graphics you would like.

Notice that there’s no rhyme or reason to what Bill selected or the order in which he put it on the paper. He just selected some key events from his life and placed them randomly on the paper.

Third,

start writing down your thoughts. At this point you are probably buzzing with ideas. If something has meaning to you, write it down anywhere on the paper. It’s important to write what comes to mind, not just what you think is career related. You don’t need to write any long explanations; just jot down a few keywords. For instance,

if you learned something from working at a camp one summer, just write “summer camp counselor” or whatever the position was. If you have read several biographies of Martin Luther King

Jr.and

find you quote him or follow his beliefs, write down his name. There will be time later to expand your thoughts. You can even draw little pictures if you prefer. The important thing is to just dump everything that’s in your head onto the map.

Fourth,

as you continue to write down significant aspects of your life,

don’t try to organize them in any way.

Just write them down, draw a circle or other shape around them, and keep going. You can put down ten items or forty items or four hundred items; it’s up to you.

Fifth,

staring at a blank piece of paper can be daunting. Just in case you’re stuck or still not quite sure what to put on your map, here are some final prompts that may help you remember key moments in your life:

•

Objects

you use and/or enjoy

• Computers

• Musical instruments

• Books

• Binoculars

• Skateboards

• Telescopes or microscopes

• Sailboats

• Paintbrushes

• Journals

•

Events

in your life, whether a moment in time or lasting for years

• Jobs you’ve held—awful to wonderful

• Taking a fantastic class

• Tutoring a child

• Baking cookies for the holidays

• Designing a Web site or your Facebook page

• Acting in a school play

• Running for office in a school election

• Playing sports

• Creative projects

• Adventures/risks you’ve taken

• Assignments, papers, or projects you’re proud of

• Family heritage/culture

• Hobbies

• Ideas you have developed

• Internships

• Places you’ve lived or traveled

• Summer activities or vacations

• Volunteer activities