You Might Remember Me The Life and Times of Phil Hartman (23 page)

Read You Might Remember Me The Life and Times of Phil Hartman Online

Authors: Mike Thomas

Come September, Phil was back in New York for

SNL

’s eighteenth season. Thanks in part to Carvey’s departure midway through, Phil shone more than ever before. Another character of his had caught on, too. During the latter half of season seventeen, he’d achieved some measure of breakout success playing a mean Frank Sinatra. Literally—the guy was an asshole. And very funny in the way that assholes who don’t care they’re assholes can sometimes be. Unlike erstwhile cast member Joe Piscopo’s more respectful and far less belligerent portrayal of the Chairman of the Board, Phil’s Frank was all venom and swagger. “The Sinatra family was not happy with the impression Phil was doing at all,” Piscopo claimed in

Live from New York.

Phil’s Sinatra debut, in a sketch written by Bonnie and Terry Turner, was inspired by a letter from Ol’ Blue Eyes to then-reluctant pop star George Michael that was published in the

L.A. Times

(Sample excerpt:

“And no more of that talk about ‘the tragedy of fame.’ The tragedy of fame is when no one shows up and you’re singing to the cleaning lady in some empty joint that hasn’t seen a paying customer since Saint Swithin’s day.”

). In it, Carvey played a self-infatuated Michael (“Look at my butt!”) opposite Phil’s Frank. In a few other Sinatra outings, Phil ring-a-ding-dinged with Hooks alongside her cloyingly earnest (and, thus, quite hilarious) Sinead O’Connor with Tim Meadows’s Sammy Davis and again as the secret lover of First Lady Nancy Reagan. (Phil played Ronald Reagan as well.)

Most notably, he scored big as the be-tuxed host of a cockamamie talk show called “The Sinatra Group.” Dreamed up by Robert Smigel and based on PBS’s

The McLaughlin Group,

it stars a bald and morose Hooks as O’Connor (whom Sinatra refers to as “Sinbad” and “Uncle Fester”), guest star Sting as a surly and scowling Billy Idol, Chris Rock as marble-mouthed rapper Luther Campbell, and Mike Myers and Victoria Jackson as grinning Sinatra sycophants Steve Lawrence and Eydie Gorme.

Billy Idol:

I think you’re a bloody, stupid old fart!

Frank Sinatra:

You’re all talk, blondie! You want a piece of me? I’m right here!

Billy Idol:

Don’t provoke me, old man.

Frank Sinatra:

You don’t scare me. I’ve got

chunks

of guys like you in my

stool

!

When Ol’ Blue Eyes himself caught wind of the sketches, he picked up the phone and called his youngest daughter, Tina, for her take. She told him it was cool to be parodied on

SNL

and then phoned Lorne Michaels’s office to request videos of Phil’s Sinatra bits for her dad. When Phil ran into Tina on a couple of occasions, he was thrilled to hear that Frank got a kick out of his work.

But even Phil’s Sinatra did relatively little to goose his

SNL

, and thus his overall showbiz, profile. An impression as opposed to an original invention, it was no Church Lady and it was no Wayne Campbell. Rising to that level, or anywhere close, would require someone even more powerful than the Chairman of the Board.

Chapter 12

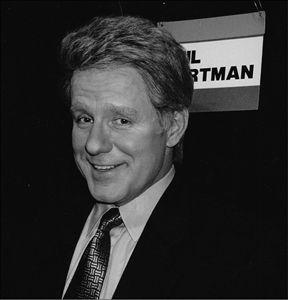

Phil as Bill Clinton on

SNL

, 1992. (Credit: Makeup by Norman Bryn,

www.makeup-artist.com

, photo copyright Norman Bryn, all rights reserved)

On October 12, 1992, during the second episode of season eighteen and shortly after Phil filed paperwork in L.A. to legally change his last name from Hartmann to Hartman, controversial Irish pop star Sinead O’Connor appeared as

SNL

’s musical guest and sang Bob Marley’s protest song “War” a capella. “We have confidence in the victory of good over evil,” she intoned, staring directly into the camera with an I-mean-business expression. As she uttered the word “evil,” O’Connor held up a photo of Pope John Paul II and tore it two, four, then eight pieces before tossing the shreds toward a stunned audience and proclaiming, “Fight the real enemy.” On orders from the show’s director, Dave Wilson, the applause sign remained dark and silence enveloped Studio 8H. Along with many others, Phil thought O’Connor’s actions were uncalled for and distasteful. Not only did she disrespect the Catholic faith and its adherents, she cast a pall on whatever comedy came after—including a sketch called “Sweet Jimmy, the World’s Nicest Pimp.”

At dress rehearsal, O’Connor had used the picture of a child, thus setting up her live shot. Then, on air, she whipped out the Pope glossy to audience gasping. Phil was standing in the wings with the next week’s guest star, Joe Pesci, watching it all unfold on a monitor. “Fuckin-A!” he exclaimed when the Pope shredding commenced. Pesci was equally floored, hissing, “What the fuck is the matter with that bitch!” Smigel was in the wings as well and remembers everybody “just avoiding her” afterward. Besides inappropriately flaunting her religious and political views, he says, O’Connor broke one of live television’s unofficial rules: Don’t surprise the producers. “If that happens too many times, then there won’t be a live show. That’s how we looked at it and I think that’s how Lorne looked at it. It’s something that’s precious and rare, allowing something to go on totally live and to live with the kinks and the flaws. And I think Lorne was really afraid that it was going to inspire copycats in musical acts—that kind of thing.”

When the show ended and everyone gathered onstage during the closing credits, as per

SNL

custom, Phil stayed back in the shadows. At the time, he wasn’t quite sure why. In retrospect, it became clearer. “I realize that in her country it is very repressive in regards to women’s rights, and I understood her motivation,” he told journalist Bill Zehme a year afterward, in an unpublished 1993 interview. “But I do think it was just ill placed. The Church, for better or for worse, represents a moral absolute. It’s a moral touchstone, and I don’t think you should attack that.”

Appearing on the Letterman show that same month, Phil’s thoughts on O’Connor’s desecration began on a serious note and devolved into shtick: Proclaiming he had been “hurt and offended” by her pushing a political agenda, he nonetheless allowed that her feelings on this “volatile issue … the whole idea of women’s rights”—(she was actually protesting the sexual abuse of children)—were justifiable. “We were taught from childhood: You do not tear up a picture of the Pontiff,” he said, beginning to crack wise. “If you have a choice between doing it and not doing it, what you do is

not

. And in school, similarly, the nuns taught us with the Catechism: You do not put Hitler mustaches on the twelve Apostles.” He was so “angry” after O’Connor’s stunt, Phil went on, that he now felt “an urge for vengeance.” His plan, if O’Connor ever had “the guts” to perform in New York again, was to leap onstage while she sang and “tear up a photo of Uncle Fester. I’ll see how

she

feels.”

Downey recalls that religion was also to blame the only time Phil argued against speaking lines with which he disagreed. “Phil came to me and he was really upset,” Downey says, and not because the October 1988 presidential debate sketch in question—in which Phil plays an extremely jaded version of news anchor David Brinkley and guest star Tom Hanks is ABC News anchor Peter Jennings—was unfunny.

“You’re offending people,” Phil told Downey. But what was so offensive? Downey wondered. There were no dirty words, no attacks on specific groups. “It was the strangest thing. And we sort of had to tone it down. But even then, it was one of the few times he was not very good on the show.”

Jennings:

Well, David, throughout your career, you’ve been known for your cynicism, but certainly you haven’t lost that much faith in the presidency.

Brinkley:

Well, Peter, as I get older, I find I’ve lost faith in a good many things—country, family, religion, the love of a man for a woman. I’ve reached a point where it’s struggle to get up in the morning, to continue to plow through a dreary, nasty, brutal life … of terrible desperation … at the end of which we’re all just food for maggots.

Usually, though, Phil was chilled out and unflappable; it took a lot to get him worked up. Lovitz, for one, would try—and always fail. Sometimes Phil even played along, as in this phone bit they did offstage.

Lovitz:

Hello, is Brynn there?

Phil:

Who is this?

Lovitz:

It’s her lover, Bob.

Phil:

Oh, hello, Bob. Hold on.

Lovitz:

No, Phil, it’s me, Jon!

Phil:

Oh! Jon. Thank God! I didn’t recognize your voice.

Lovitz:

That’s because this is Bob.

Phil:

What?! Why I oughta …

According to Phil’s former Pee-wee cohort Dawna Kaufmann, who was hired as an

SNL

writer for the ’92–’93 season, Phil also appeared the model of calm when Brynn stopped by one day to visit and mingle. Kaufmann liked Brynn, but thought her kind of odd—especially on this occasion. “The first time she showed up at the office, we were all in the big conference room, and she comes in and starts sitting on all the guys’ laps and kissing them and putting her tongue in their ears,” Kaufmann says. “And everyone thought, ‘Oh, isn’t that funny?’ And I thought, ‘How could she do this to Phil? This is so humiliating to him.’ And he’s laughing like he didn’t care. How could you not care?”

* * *

As the 1992 election drew nearer Phil’s Clinton impersonations became more frequent as more political sketches got airtime. On Sunday, November 1, Phil and Carvey hosted a politically themed clip show titled “Presidential Bash.” Besides Clinton, Phil also portrayed the vice presidential debate-bungling Admiral James “Who am I? Why am I here?” Stockdale, out on a joyride with Ross Perot (Carvey). It had originally aired a week before, and afterward calls had flooded into

SNL

from military vets who thought the sketch disrespectful. Smigel says Phil never seemed reluctant to play the part, but that he later expressed some guilt about mocking the former Vietnam prisoner of war and subsequent Congressional Medal of Honor recipient.

Two days later, on November 3, when the silver-tongued Democrat from Arkansas—already nicknamed “Slick Willie”—beat out Republican incumbent George H. W. Bush for the most powerful post on Earth, Carvey’s prediction came true: Phil won, too. “Phil was incredibly excited that he was going to get to be the president,” Smigel says. “In a way that you wouldn’t expect, because he was so laid-back. He’d seen Dana be George Bush and how important that was to Dana’s career.” Phil even wrote a personal letter to President-elect Clinton, Smigel says, “trying to be very serious and thoughtful” about his new responsibility. “In the overall scheme of his life,” Phil said, “we’re either a thorn in his side or a finger tickling his ribs.” In the overall scheme of Phil’s life, Clinton’s installation as leader of the free world was a game changer.

“I don’t think we’ll be particularly vicious at first,” Phil told

The Boston Globe

in late November, a few weeks after Clinton’s election, of the “choice gig” that was now his for at least the next four years. “When Bush took office, we gave him one hundred days to establish a persona. Dana Carvey’s take on Bush evolved from Bush’s quirky traits—‘It’s bad! It’s baad’ and the manic hand gestures. So far Bill hasn’t given me any broad hook.”

Eleven days after America voted the real guy into office, a torch of sorts was passed in a so-called “cold open” (prior to

SNL

’s opening credits) that featured Carvey as a vanquished George Bush calling up campaign contributors to apologize for letting them down.

Bush’s assistant, Marybeth:

Sir, I almost forgot: it’s 11:30, and President-elect Clinton is about to go on CNN.

Bush:

Well, thank you, Marybeth. [Bush picks up remote control and turns on television. The U.S. presidential seal appears onscreen.]

Announcer:

Ladies and gentlemen: the President-elect of the United States. [Shot dissolves to a grinning Clinton]

Clinton:

Live, from New York, it’s Saturday Night! [The audience cheers; Bush shakes his head glumly and slumps in his chair.]

Bush:

I—I—I used to say that!

Then came December 5, 1992. Until then, Phil’s most successful Clinton portrayal to date had been pre-election, when he played the then-governor bragging about Arkansas’ dismally low literacy rate. This was not that—by a long shot.

Scene: President-Elect Bill Clinton [Phil] and two Secret Service agents [Kevin Nealon and Tim Meadows] jog into a Washington, D.C., McDonald’s.