You Must Remember This (5 page)

Read You Must Remember This Online

Authors: Robert J. Wagner

Colleen Moore, the popular flapper of the 1920s and a brilliant stock investor, bought a house on St. Pierre Road, and Warner Baxter came in about the same time. By World War II, movie people were setting up shop in Bel Air on a weekly basis, as it had become a more prestigious address than Beverly Hills. Judy Garland would build a ten-room Tudor house for herself at 1231 Stone Canyon Road, just up the street from the stables.

Bel Air had an interesting dynamic in those early years. Although you were only twenty minutes from Hollywood and its core industry, the town had a rural feel. Alphonzo Bell had his offices on Stone Canyon Road, and when he sold that property the office and the stables he had built there were redesigned and reconfigured to become the foundation of the Bel Air Hotel.

A lot of the rooms at the hotel were once horse stalls, and I’m

particularly fond of a large circular fountain on one of the patios where I used to water my horse when I was a boy. Part of Bell’s property was converted into the Bel Air Tea Room, where I bused tables as a kid, with John Derek working alongside me.

Besides busing the tables, I washed dishes and occasionally waited on tables. It sounds like a typical summer job, but it was a life changer, because I became close friends with another kid named Noel Clarebut. Noel introduced me to his mother, Helena, who ran the dining room and the antiques gallery at the hotel.

Helena became a tremendous influence on my life. A European, she loved the theater, food, classical music, dogs—all the finer things in life. I didn’t have any of that. My family was Midwestern, with a utilitarian, bricks-and-mortar set of values.

Horses were very much a part of my life from the time we arrived. Robert Montgomery was responsible for making it easy to ride there, because he promoted the construction of bridle trails that wound their way through Bel Air in more scenic routes than were available in Beverly Hills.

My first horse was named Topper, after Hopalong Cassidy’s horse. He was a great horse, and I had him until his old age, when my father did exactly as Robert Redford’s character did in

The Electric Horseman

: he took Topper back to the breeder from whom he’d bought him. The breeder had a thousand acres, so Topper was unloaded into the pasture and slapped on the rear end, then went off to live out his days grazing. For Topper, life was a circle—he was born there, and he died there. At the time a lot of people didn’t fuss over their animals; they were part of the property more than they were part of the family, but I’m proud to say that my father didn’t feel that way, and he passed that same feeling on to me. Animals deserve nothing less.

A photo of me with my horse Sonny.

Courtesy of the author

Sonny was another horse I adored. He was a gentle soul, brown, with big hips and splashes of paint on his shoulders. Technically he was my father’s horse, but Sonny and I bonded in a very special way. His previous owner had taught him a routine that I maintained and amplified at performances at shows and fairs.

We’d make an entrance with him pushing me out. I would pretend to trip and fall. Sonny would lie down next to me, and when he was flat on the ground I’d grab a strap that was around his stomach. He’d get up and lift me with him, and I would hop on his back. We’d make an exit, then come back with an American flag in Sonny’s mouth. He’d toss his head a few times, which caused the flag to wave, and the crowd would reliably go nuts. Then he would take a bow.

For a boy who loved horses and was beginning to love applause, it was a surefire act, and a lot of fun to perform.

Years went by and Sonny got cataracts, so, just as he had with Topper, my dad took him back to the breeder. I got a chance

to say good-bye to him, but losing him bothered me for years. It still does.

It sounds impossible now, almost like something out of science fiction, but the fact is that before and after World War II Los Angeles had one of the best mass transit systems in America. Electric streetcars connected Orange, Ventura, Riverside, and San Bernardino Counties with no exhaust and no smog—the trolley lines ran on overhead electric wires.

Los Angeles and the suburbs around it were expanding exponentially all during my childhood, but the air remained remarkably clean. I know: I rode those streetcars because that’s how I went to the movies. Occasionally I would take my bike and head to Westwood to see a movie. But if the film I wanted to see was in Hollywood, it was too far for the bike ride, so I’d walk from our house to UCLA, and grab a bus to Beverly Hills, then catch the trolley. (Occasionally, my father would drive my mother, my sister, and me, and sometimes he’d even come in with us.)

The trolleys began in 1894 with horse-drawn cars. By 1895 there was an electric rail line connecting Los Angeles and Pasadena, and a year after that a line opened that connected Los Angeles with what would become Hollywood and Beverly Hills, all the way to Santa Monica.

During World War I you could go from downtown Los Angeles to as far away as San Bernardino, San Pedro, or San Fernando on the trolleys. There was a trip called the Old Mission that went from Los Angeles to Busch Gardens, all the way to Pasadena and San Gabriel Mission. The Mount Lowe trolley, which was actually a cable car on narrow-gauge track, went to the top of Echo Mountain. The Balloon Route ran from Los Angeles through Hollywood, Santa Monica, Venice Beach, Redondo, and back to Los Angeles via Culver City. (I shudder to think how long that round trip must have taken.)

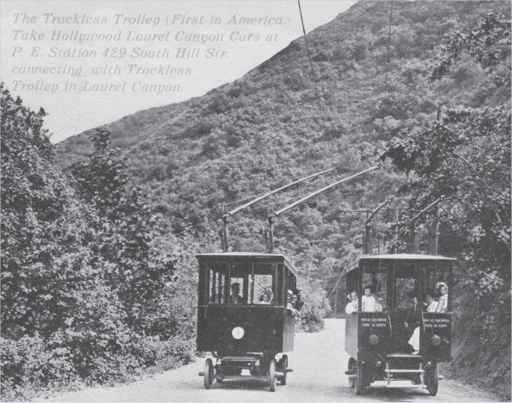

Two trackless trolleys (the first in America) running through Laurel Canyon.

Mary Evans Picture Library/Everett Collection

Apparently the trolleys took a hit in the 1920s as the population became more prosperous and people started buying cars, but with World War II, gasoline and tire rationing revived the trolley lines, and ridership hit an all-time high of 109 million in 1944.

By then, Los Angeles had two separate trolley systems, commonly known as the Red Cars and the Yellow Cars. Pacific Electric owned the Red Car line, and National City Lines owned the Yellow Cars.

I generally took the Red Cars, which ran from Union Station downtown all the way to the beach—an east-west line. To get there, it wound through the middle of Beverly Hills, through the upper

part of Hollywood, then crossed over to Sunset. The Red Cars were great—they were fifty feet long, and ran between forty and fifty miles an hour.

The transit system was remarkably well engineered, efficient, and, in modern terms, environmentally sound. When I was riding the Red and Yellow lines they were at their height—there were nine hundred Red Cars running on 1,150 miles of track covering four counties. There aren’t that many people who remember them anymore, but they were a crucial factor in how Los Angeles developed the way it did. Because the trolleys made travel simple—not to mention cheap—they encouraged very expansive development. As late as 1930, more than 50 percent of the land in the LA basin was undeveloped. The population spread out over a very large area of land, which is why in my memory, and in my friends’ memories, Los Angeles seemed uncrowded and undeveloped—almost sylvan.

One of the red cars passing in front of Grauman’s Chinese Theater on Hollywood Boulevard. In an astonishing coincidence, Grauman’s just happens to be showing one of my movies.

Courtesy of the author

Of course, it all changed. The sheer expanse of Southern California made it perfect for the automobile, and the basic disposition of the American public toward independence probably made the decline of the trolleys inevitable. Making the changeover faster than it had to be was the dismantling of streetcar systems in favor of buses by a number of companies, including General Motors, Firestone, and Standard Oil, who stood to make a lot more money with buses than with electric power.

By the early 1950s, when I was a young leading man at 20th Century Fox, cars had displaced the trolleys as the primary means of travel in Southern California. Freeways that sixty years later are now often impassable, not to mention impossible, were being constructed. By 1959 the only trolley line that was still operating was LA to Long Beach, and that was discontinued in 1961. The trolley cars were chopped up and destroyed; some were sunk off the coast. It was a terrible waste of valuable historical artifacts.

If you want to see remnants of the great Los Angeles trolley cars, you can go to a museum in Perris, California, seventy-four miles (by freeway!) from Los Angeles, where they have both Red Cars and Yellow Cars on display. Now the only way you can enjoy even a vestige of trolley culture is to go to downtown Los Angeles and ride Angel’s Flight, a historical funicular that takes you just three hundred feet uphill.

One of the favored places in Southern California is the beach, where it’s warmer in winter and cooler in summer than it is farther inland. When people wanted to get out of town completely in the warmer months, they would often head for Big Bear or Lake

Arrowhead, where the Arrowhead Springs Hotel was partially financed by Darryl Zanuck, Al Jolson, Joe Schenck, Claudette Colbert, Constance Bennett, and a few others.

(A word about celebrity financiers—they were usually like celebrities today who invest in sports teams. The amount of money that actually changed hands was minor; the stars were given some of the perks of ownership in return for whatever glamour their celebrity brought to the establishment.)