You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine (23 page)

I felt my sheet jerk across my face, blocking my vision. Someone was tugging on it, trying to get my attention. I turned right, readjusting myself, to find my eyeholes exactly level with a pair of eyes, brown like my own. Height like my own, body like my own. I had a strange, excited feeling that I had found myself: I was real, I was really there. Then the voice of a full-grown man came muffled through the front fabric that was his face.

“What do they mean, ‘unremember’?” he asked, his voice urgent.

I pointed at the podium to say that he should listen, it would totally be explained.

“Do they mean forget?” he asked.

I shrugged from under my sheet and pointed again. Other sheeted people were glancing toward us now, swiveling their heads or tilting their bodies around.

“Because I don’t know how to try to do that,” he said, sounding increasingly upset. “I mean, I could stop talking about it, but I couldn’t stop

knowing

. I couldn’t do that. Nobody could do that.”

knowing

. I couldn’t do that. Nobody could do that.”

He grabbed my arm and I shook him off.

“You’re nothing like me,” I said to him loudly, so that everyone around us could hear. I wanted them to know: though we may have looked alike with our white sheets and brown eyes and same heights, I was made of a wholly different kind of material. He was in Darkness, groping around for what these rules might mean. Now that I was here, now that I had escaped myself, I would be Bright. I would do the rules to the letter, no question, and their meaning would become apparent as I saw what they made of me. In all my life, I had never known what life demanded of me. Now that I knew, I would do it even if I didn’t really understand what it was for.

It means unremembering the capitals of states and the denominations of currency and the nuclear power plant. All our troubles began with the power plant. It means unremembering anything made with chicken, which is a highly toxic Dark meat: even thinking about this substance can cause irreparable harm to yourself and to those around you. And most of all it means unremembering yourself: waking like an amnesiac to a world beauteous in its unassociations with pain, worry, strife. When the world is clean it shines Bright in its blankness. When the body is clean it rises ghostly into the Light.

I looked around for the man who had accosted me, but he was lost, reabsorbed by the throng of sheets. His questions had made me miss something in the Manager’s speech, something I didn’t know how to get back. Maybe I could ask my partner what I had missed, what other dangers I needed to avoid. Maybe my partner would be nice and not remind me of anything dangerous. Then the applause broke out all around me, loud and unhuman like the waves or the rain, and it was a moment before I remembered to join in, flinging my hands together in front of me, clapping until they hurt, trying to create in real life the small picture of an ideal Churchgoer that I had in my mind.

As we thronged from the room, sheets dragging across the carpet, someone stopped me and gave me a slip of paper that read

E38

. “Your room assignment,” she said, her voice upbeat but not inspiring confidence. As I filed out the doorway into the corridors beyond, I saw a slight, sheeted figure up by the podium being reprimanded by the Regional Manager. I couldn’t help thinking it was the man I had met before, the man who was my size, the man who made me miss that key part of the speech I needed to become the ideal person I had come here to be, a person who wasn’t.

E38

. “Your room assignment,” she said, her voice upbeat but not inspiring confidence. As I filed out the doorway into the corridors beyond, I saw a slight, sheeted figure up by the podium being reprimanded by the Regional Manager. I couldn’t help thinking it was the man I had met before, the man who was my size, the man who made me miss that key part of the speech I needed to become the ideal person I had come here to be, a person who wasn’t.

IN THE HALLWAY OUTSIDE THE

conference room, it was easy to pretend I knew where I was going: I followed the others, who filed unanimously toward a tight, cramped back staircase painted a nostalgic shade of mint. We were all new intake, fresh bodies for the Church to process, but as far as I could tell I was the only one who didn’t know the layout of the building. The others navigated it by instinct, down flight after flight of stairs, taking the sharp turns of the staircase with ease, while I let my body get pushed along by their collective motion. I couldn’t understand how they knew what to do — it was the first day and I had already fallen behind. The crush of bodies was a slow river of white, crowding our way to the goal. It reminded me of something I might once have seen on a nature documentary, the spawning of sharks or salmon.

conference room, it was easy to pretend I knew where I was going: I followed the others, who filed unanimously toward a tight, cramped back staircase painted a nostalgic shade of mint. We were all new intake, fresh bodies for the Church to process, but as far as I could tell I was the only one who didn’t know the layout of the building. The others navigated it by instinct, down flight after flight of stairs, taking the sharp turns of the staircase with ease, while I let my body get pushed along by their collective motion. I couldn’t understand how they knew what to do — it was the first day and I had already fallen behind. The crush of bodies was a slow river of white, crowding our way to the goal. It reminded me of something I might once have seen on a nature documentary, the spawning of sharks or salmon.

We skipped one unmarked entrance after another, then suddenly the sheeted bodies were passing through a blank doorway painted glowingly green. In this new, subterranean corridor our unified motion disintegrated. Eaters split off to look for their assigned spaces while I pressed my back against the wall, trying to breathe, trying to fake a type of composure that would indicate that I was brimming with Light, quick to shake off the Darkness. It was while I hid here, in plain sight, that I began to notice that there were other Eaters like me who were not adjusting well. There in the midst of a traffic of white, they stood frozen, staring ahead of them or covering their eyes. Backs hunched, heads down in their hands, they looked as though they were wishing themselves out of this place or mourning their lack of know-how. Some came out of their stupor on their own and headed casually to their quarters; others were collected by low-level Managers and led away.

Then I saw a flash of skin in the white throng and some blue and green. In the sea of white, these colors looked wrong, a stain that was somehow moral. It took a moment for the colors to resolve into the shape of a human being, but when they did I recognized him instantly as one of the Disappeared Dads I had seen on TV. He had vanished while watching his eight-year-old son playing soccer in the park. He wore a green plaid button-up shirt and blue jeans, and he was pacing around the crowded floor with his left hand in his pocket and his right hand up to his ear as though he were talking on a cell phone. “No can do, no can do,” I heard him say out loud, again and again. He looked the same as he had on the news, only his face was vividly pink.

As I watched him talk on his imaginary cell phone, I saw a pair of Managers come up next to him, sheeted up in coverings that bore the shape of the Renunciation Mouth. They spoke to him, poked at his exposed flesh. Their voices were muffled, but I could tell they were trying to get him to put his sheet back on. “No can do,” he said. “I gotta be comfortable. I gotta be comfortable. No can do. Have you seen my slippers?” They looked at each other and grabbed him by the arm. Gently, firmly, they pulled him out of my sight, into the crowd beyond.

I looked around and saw a girl next to me, who had been watching them, too.

“Did you see that?” I asked.

“No,” she replied.

“It was one of the Disappearing Dads,” I said. “Hank. Or something.”

“I don’t think we’re supposed to remember that,” she said, sounding nervous.

“Where do you think they’re taking him?” I asked.

She shook her head.

“Do you know where E38 is?” I asked.

But she was already walking away.

BY THE TIME I FOUND

E38, my partner was already inside waiting for me. I had expected a room, but what I found was more like a medical examination tent, set up within the larger central space for emergencies. Instead of walls we had curtains: deep red curtains made of cheap velvet, strung up on metal rods that shook when someone heavy walked by. There was a small collapsible table and a rolling rack for holding an IV or a coat. A steel-rimmed mirror in the corner turned out to be a to-scale painting of the curtains, so that you stood in front of it expecting to see yourself, and instead you saw Nobody. One double-size cot done up in stiff red sheets sat in the center of a room that was barely larger. A girl lay atop this cot, sheetless and splayed out in the center like a starfish, so that she took up roughly the entire space. She lifted her head and glared at me.

E38, my partner was already inside waiting for me. I had expected a room, but what I found was more like a medical examination tent, set up within the larger central space for emergencies. Instead of walls we had curtains: deep red curtains made of cheap velvet, strung up on metal rods that shook when someone heavy walked by. There was a small collapsible table and a rolling rack for holding an IV or a coat. A steel-rimmed mirror in the corner turned out to be a to-scale painting of the curtains, so that you stood in front of it expecting to see yourself, and instead you saw Nobody. One double-size cot done up in stiff red sheets sat in the center of a room that was barely larger. A girl lay atop this cot, sheetless and splayed out in the center like a starfish, so that she took up roughly the entire space. She lifted her head and glared at me.

“You’re late,” she said.

“I got lost,” I said.

“How could you get lost?” she asked. “We got directions at the meeting.”

I thought about explaining the guy, the guy who made me miss part of the speech, but instead I just shrugged.

“I’ll help you next time,” she said. She peered into my sight holes and added: “It reflects badly on us when half of us is late.”

I took in her small, heart-shaped face, the pointy chin, the dark hair cut in a long, blunt bob not all that different from my own. She had dark brown eyes like mine and skinny, fragile-looking arms. In a taxonomy of women we would have been side by side. I wondered if she was pretty: I was so far from remembering how that concept worked and what it looked like. I wondered if she was prettier than I used to be.

“Shouldn’t you be wearing your sheet?” I asked.

She looked at me strangely again.

“They explained that, too, in the speech,” she said. “Were you even there?”

“I was there,” I said. “But a Dark person in the audience interrupted my access to the information.”

“Okay,” she said. “I’ll explain it, but you need to avoid situations like that in the future. Every interaction with Darkness brings down your Light levels, and you can pass it on to me too because we are One Person.”

I nodded, and she explained. This small shared space was the only place in the Church where we were allowed to appear uncovered, sheetless, our sticky limbs exposed to the air. This was for some or all of the following reasons: The fabric that shielded us from rays of Darkness also interfered with the production of vitamins that we needed in order to keep living, at least until the day when our living was complete. Or our bodies needed to see another body every once in a while, see their naked face and little white teeth, to remind ourselves that we were not yet ghosts, only flesh pointed toward that goal. Or the sheets were primarily a way of communicating, we needed them only in the gathering places as a statement made to one another that knowing one another even as little as we did was a temporary situation, bound to end soon. Ultimately, seeing our partner sheetless helped to erode our memory of our own particular face, which was unviewable within the Church owing to the lack of mirrors.

I pulled the sheet up over my head and let it fall to the floor, crumpled. It was a relief — to pull the sheet from my body, to peel it from me where it had fused to my skin and yellowed, to expose my tingling arms to the air — but somehow it annoyed me to show my face to this strange new girl. She reminded me of B, consuming my face with her eyes, thickening the air with her presence. To see her lounge around in her skin as if it were the only natural thing to do highlighted how unnatural anything was for me now. I decided to call her Anna, which wasn’t so far from my own name. It was palindromic, which seemed to suit someone who was destined to become my mirror. It was short and easy to remember. It was the name I had given to my favorite doll, the one that I asked my mother to throw away after I noticed something overly human about its eyes.

My hair clung to my skin like a bark. “You look exhausted,” Anna said, sitting forward on the cot and looking at me hard from both eyes. “Much more tired than me. I’ll work on getting my face a little bit wearier, but I always tend to sleep well. I think it would be better if you’d work on getting some more rest. The closer we are in body and appearance, the easier it’ll be to merge our life.”

I didn’t say anything.

“If we are as One Person, spread out over two bodies,” she said in a pert, authoritative tone, “we’ll halve our load and ghost much earlier.”

“I know,” I said, but I didn’t.

Then from behind me I heard the sound of the curtain being pushed aside, and a dinner tray slid into our space, its contents obscured under a gleaming metal cover. I picked it up and looked out into the corridor to see if another was coming, but there was nobody there.

I turned back to Anna and told her: “There’s only one.”

“Of course there’s only one,” she said. “We share everything now.”

I looked down at the shining tray. I had no idea what it might be. A purer food, probably, or maybe a less pure one if they wanted to test our powers of distinction. I had to remind myself to keep my hopes down, that it might not be food at all — though the thought made my stomach ache with hunger. I took a breath and then I lifted the cover off the tray.

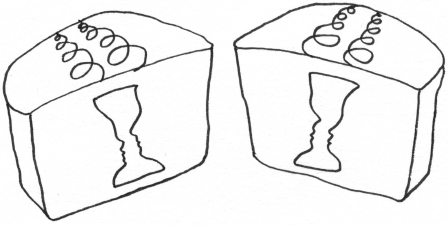

What I found there was a small heap of Kandy Kakes, twelve of them piled on a white plate. They were just as I had pictured them over the last few difficult months: a double squiggle of frosting-flavored icing gracing the dark, hard surface of its chocolate-armored puck. Just as I had pictured — only, if possible, even more beautiful.

I almost couldn’t believe this was really happening. I would grow clearer, thinner, Brighter, a more perfect vessel for my ghost. I felt a great burden lift from me, the burden of worry over what I was, what was becoming of me. With the help of these Kandy Kakes, I would finally become better in the Bright future ahead.

“Why are you crying?” asked Anna, annoyed.

I tried to explain: “I’ve waited so long for these.”

Other books

Nine Volt Heart by Pearson, Annie

The Gift of Numbers by Yôko Ogawa

NaGeira by Paul Butler

The River of Souls by Robert McCammon

Angel Souls and Devil Hearts by Christopher Golden

Wolf3are by Unknown

Kentucky Rich by Fern Michaels

The Art of War by David Wingrove

The Siege by Kathryn Lasky