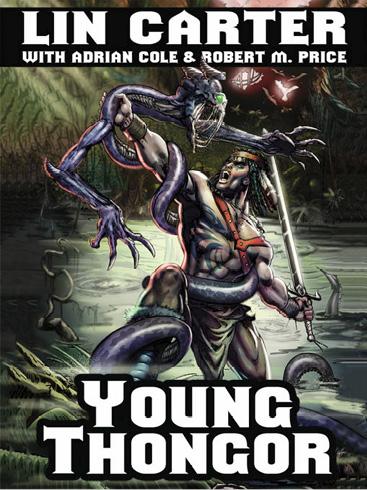

Young Thongor

Authors: Lin Carter Adrian Cole

ALSO BY LIN CARTER

The Man Who Loved Mars

The City Outside the World

Tower at the Edge of Time

The Quest of Kadji

Beyond the Gates of Dream

The Black Star

TERRA MAGICA

Kesrick

Dragonrouge

Mandricardo

Callipygia

WORLD’S END

The Warrior of World’s End

The Enchantress of World’s End

The Immortal of World’s End

The Barbarian of World’s End

The Pirate of World’s End

ZARKON, LORD OF THE UNKNOWN

The Nemesis of Evil

Invisible Death

The Volcano Ogre

THONGOR

The Wizard of Lemuria (Thongor and the Wizard of Lemuria)

Thongor of Lemuria (Thongor and the Dragon City)

Thongor Against the Gods

Thongor at the End of Time

Thongor in the City of Magicians

Thongor Fights the Pirates of Tarakus

YOUNG THONGOR

LIN CARTER

WITH ADDITIONAL MATERIAL BY ROBERT M. PRICE

EDITED AND WITH A FOREWORD BY ADRIAN COLE

DEDICATION

I am indebted to

Robert Price and Morgan Holmes

for their invaluable advice and assistance

in aiding me to compile this collection.

—Adrian Cole

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Copyright © 2012 by Wildside Press, LLC.

Published by special arrangement with Robert M. Price,

John Gregory Betancourt, and Lin Carter Properties.

For more information, contact wildsidebooks.com

“Diombar’s Song of the Last Battle” first appeared in

Dreams from R’lyeh

, 1975 (Arkham House). “Black Hawk of Valkarth” first appeared in

Fantastic Stories

, September 1974; © Ultimate Publishing Company Inc. “The City in the Jewel” first appeared in

Fantastic Stories

, December 1975; © Ultimate Publishing Company Inc. “Demon of the Snows” first appeared in

The Year’s Best Fantasy Stories

, Volume 6, 1980, edited by Lin Carter (DAW Books Inc.) “The Creature in the Crypt,” based on a title by Lin Carter, is published in this form for the first time. “Silver Shadows” by Robert M. Price first appeared in

Crypt of Cthulhu

, no. 99—Lammas 1998. “Mind Lords of Lemuria” by Robert M. Price is an original tale, published here for the first time. “Keeper of the Emerald Flame” first appeared in

The Mighty Swordsmen,

1970, edited by Hans Stefan Santesson (Lancer Books Inc.) “Black Moonlight” first appeared in

Fantastic Stories

, November 1976; © Ultimate Publishing Company Inc. “Thieves of Zangabal” first appeared in

The Mighty Barbarians

, 1969, edited by Hans Stefan Santesson (Lancer Books Inc.)

FOREWORD

It would be difficult to identify the first Barbarian ever to wield a sword and tangle with sorcerers, monsters and other burly ruffians of similar ilk. His fantastic adventures would not necessarily have been recorded anywhere, but would almost certainly have been part of a rich tradition of oral story telling, around campfires, long before cities were conceived and the birth of what we, rather arrogantly, call civilization. The heroic tradition did eventually pass to the written word, creating immortal warriors whose names yet conjure up visions of splendid deeds and valor beyond the call of duty: Gilgamesh, Ulysses, Hercules, Beowulf, Sinbad, Cuchulainn, Viracocha, to name but a few.

Thongor, Lin Carter’s most notable heroic Barbarian, first saw print in 1965 in

The Wizard of Lemuria

1

and at once it could be seen that he undoubtedly had his ancestral roots in many of these ageless champions. Lin Carter, who was himself a champion of the heroic fantasy genre and an avid, omnivorous reader of its numerous branches, was more than a little familiar with the archetypal Barbarian. Thongor, however, has two very distinct roots, both of which Carter himself would have been the first to acknowledge.

These are Conan the Cimmerian, Robert E. Howard’s

nonpareil

muscle-bound superman of an imaginary history set around 10,000 B.C. and John Carter, Edgar Rice Burroughs’s superlative swordsman of Barsoom, or Mars. They are two entirely different characters, adventuring in very dissimilar worlds, though sharing certain common traits, not least of which is their appetite for action, their fearlessness in the face of impossible odds and the kind of determination to succeed that once built spectacular, world-spanning empires. Lin Carter drew heavily and unashamedly on these two robust fictional heavyweights when he put his own Barbarian together. The result is an unusual fusion, an affectionate tribute to two of the lasting champions of fantastic fiction.

Thongor himself is “…

cast very much in the mold of Conan

…”

2

apart from the occasional show of somewhat rough-hewn gallantry (as with Conan himself) he could hardly be mistaken for the gentlemanly John Carter, although he behaves and speaks very much like Burroughs’ greatest creation, Tarzan, on occasion. In the tales that comprise Young Thongor, the Cimmerian’s influence is particularly strong, while in the novels that follow on from this collection, John Carter and the characters of his world come more into focus as inspirations for the ensemble of Lemuria.

This prediluvian continent, while evidently prehistoric and pulsing with appropriate monsters, conjures up regular comparisons with Barsoom, which seems to be even more its blueprint than the Hyborian world of Conan. It is a compliment to Carter’s energy and enthusiasm for his creation that the confusion of two such worlds and potential for anachronism and resulting dissonant clashes never actually materialize. In a bizarre kind of way, Thongor’s saga works and works well.

As for the Barbarian’s name, Lin Carter chose it quite deliberately and has said, “…

‘Thongor’ has grim weight to it, solidity, and the ring of clashing steel. The character is obviously a fighting-man; you can sense that from the sound of his name alone

…”

3

And what of Lost Lemuria itself? In some ways it has been the poor relative of Atlantis, down through the ages. Initially it appears to have been a quasi-scientific explanation for there being lemurs in Africa and India, in the form of a geological bridge that spanned the ocean between two continents. The continental drift theory put paid to that, but Madame Blavatsky and her redoubtable Theosophists clung to the belief that Lemuria did actually exist and that it was the home of very curious inhabitants indeed. Lin Carter, much read in such lore, was familiar with all this, of course.

Rather than utilise the more familiar territory of Atlantis (as found in Howard’s King Kull stories) Carter opted for the lesser-known alternative. Howard referred, albeit briefly, to Lemuria in his ‘prehistory’, which prefaces the Conan saga,

The Hyborian Age

.

4

Carter, who worked with Sprague de Camp on a number of Conan and Kull pastiches, was thoroughly

au fait

with this material and put it to good use in the Thongor epic. Hence Thongor’s Lemuria still has strong links to the age of dinosaurs and its own history is steeped in conflict with reptile-beings, more saurian than human. Just as King Kull had to deal with lizard men who stubbornly refused to sink down into the swamps of oblivion, so does Lemuria have its Dragon Kings and their spawn. Add to this the half-forgotten technology of a former age,

à la

Barsoom, together with denizens who could have stepped straight from the dead sea-bottoms of that war-like world, and you have a colorful mix of culture, biology and history.

Quite apart from the Hyborian/Barsoomian connection, Lin Carter also drew heavily on the pulp tradition for the Thongor saga, a tradition that goes back through many of the writers and magazines that he promoted so ardently and successfully in his work as an editor. And he did not confine himself simply to the heroic elements of pulp, but drew on such diverse sources as H.P. Lovecraft, Lord Dunsany, A. Merritt and Clark Ashton Smith, to name but a few. The devout fan of pulp fiction will quickly recognise these elements in the Thongor saga and indeed, part of the fun of reading the work is in checking out the sources! One example from this volume is the story, “The City in the Jewel,” in which Thongor finds himself in an enclosed world more in keeping with Dunsany than Howard, a direct contrast to some of the other stories.

Magic vies with technology, too. There are crumbling citadels, reeking with old sorceries and demonic powers, juxtapositioned with decadent super-science straight out of Edmond Hamilton or Van Vogt.

5

This Lemuria is a

potpourri

of pulp ingredients, wildly improbable, scornful of boundaries, reminiscent of the old Saturday morning movie serials, with their fabled “cliff-hangers.” Burroughs used this technique to perfection in his own plots, and in Thongor we see the same style at work, so much so in places that one would almost expect Tarzan himself to swing out from the jungle to add weight to Thongor’s cause.

With the boom in heroic fantasy and sword and sorcery that came in the sixties, Thongor was by no means the only muscular barbarian to batter his way pell-mell through a catalogue of adventures. Conan spearheaded the advance, of course, but there was also Brak the Barbarian, creation of John Jakes, whose world and exploits therein mirrored those of Conan and Thongor and which were no less dynamic. An entire sub-genre sprang up, with an odd preponderance of “K” warriors—Kothar, Kyrik, Kandar, Kavin and Lin Carter’s own Kellory.

6

Many of these fitted into a standard set of rules, with villains, monsters and beautiful maidens who were interchangeable and who could have comfortably slipped across from one series to another, like a wandering troupe of actors, taking the stage as and when required.

Yet the success of this itinerant band of heroes opened the way for other, more ambitious characters, still toiling away within the genre, but thrusting its boundaries ever wider into more imaginative and exotic terrain. Cugel the Clever, Jack Vance’s lovable villain from the revived Dying Earth series, Karl Edward Wagner’s turbulent, passionate Kane saga (Wagner himself wrote a couple of fabulous Howard pastiche novels), Fritz Leiber’s highly polished and amusing Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser stories and Michael Moorcock’s brooding, sombre Elric and Eternal Champion novels—all wonderful examples of the development of the genre. It is a less active genre these days, but it still has its wonders, the most outstanding example of which is surely the superb Nifft the Lean series from Michael Shea.

Lin Carter first enjoyed success with Thongor, but his zealous enthusiasm could never have been confined to one character and he was soon to produce a whole wave of sagas, each of them no less heavily influenced by writers like Burroughs, Howard, Vance and others. Burroughs very obviously remained the main source of this inspiration, directly or indirectly. The Callisto series is, for some critics, too close to Burroughs and Barsoom for comfort, whereas the Green Star series, with its homage to Amtor (Venus) introduces enough variety to hold its own with Thongor. Another writer that Lin Carter greatly admired and praised was Leigh Brackett, whose own Martian stories were inspired by Barsoom. She created a Mars of her own, an evocative variation on the original theme (as did C. L. Moore with some of her outstanding Northwest Smith yarns) and Lin Carter pastiched their work with his own Mars quartet, although he drew, as always, on several other celebrated sources for his mixture. The first three of this series,

The Man Who Loved Mars, The Valley Where Time Stood Still

and

The City Outside the World

, are considered by many to be among his best works.