Your Band Sucks (28 page)

Authors: Jon Fine

“All my life I've been interested in the idea of getting overwhelmed by sound,” Mission of Burma's Roger Miller said. “Even when I was in ninth grade I would stand right in front of the amps and just do feedback for hours. Varying the sounds of the world exploding really appealed to me. It's pretty reasonable I would get tinnitus.”

Was Roger wearing earplugs back then? Of course not. Nor was Justin when his drummer was bashing the crash cymbal, nor was I on that European tour or at many of the several thousand shows I attended or played. We all wanted sound to be a physical as well as aural phenomenon. To

feel

it. LOUD, like 120 decibels. Like a jet engine in a small room. To quote the band NME:

Louder than hell is what we are

You say that we take it just too damn far

You can't understand a thing that we say

But we don't care, it's the way that we play

We play loud

Louder than hell

Fucking loud

Louder than hell.

Yes.

Exactly

. Thus, the ears go first. More specifically, your ability to hear silence goes first. “We were in Italy, and some guy took us to the forest,” Andee Connors from A Minor Forest recalled. But no soothing sounds of nature awaited him. “All I could hear was this high-pitched whine. I had a total panic attack. I bought earplugs the next day.” Though the damage, of course, had already been done.

In 2013 Laura Ballance quit touring with Superchunkâthe band she'd played bass for since 1990âbecause of mounting hearing loss and increased sensitivity to loud noise. “I can't hear that well, and I'm always saying, âWhat? What?'” she told me. “Then all of a sudden I'll be like, âStop yelling!'” And an audiologist once told David Yow that many people with hearing aids heard trebly frequencies better than Yow didâwhen they took their hearing aids

out

.

We were all chasing abandonâanimal, grunting, feral abandonâand our ears were the route of administration for something that filled the body as well as the head. Did we have any notion that losing silence might be the price of admission? Not really. Even though, as early as the eighties, Pete Townshend was warning everyone within earshot (sorry) that they, too, could end up deaf. I'm surprised at how many of us

don't

have severe hearing problems, given how loud we all routinely worked and the hundreds of shows we attended that were just massacres of volume. But you have no idea how good it felt, playing the music you centered your life on

that

loud. It made the air seem suffused with electricity. It lit you up like a city at night. People in thrall to a lesser rush end up turning tricks to afford it. Chasing ours made us slam onto our guitar or bass or the drum kit harder, push voices into higher and higher registers, scream longer, jump higher. Messing up our ears was one obvious outcome, but there was other cumulative wear and tear: we attacked our instruments and music with so much more aggression than, well, pretty much anyone else. (Look at how gently, how

politely

, dullards like Eric Clapton and Mark Knopfler play their guitars.) Many of us also developed various chronic injuries, from hurling ourselves and our bodies at the music as hard as we could, over and over again, until our knees or backs or elbows or necks told us,

Now

stop

. When James Murphy drummed in his old band Pony, he recounted matter-of-factly, “I used to throw up at every gig. I played with marching sticks”âwhich are very heavyâ“and I had no efficiency of movement, and I would just play until I barfed.”

In general, talking to middle-aged drummers is often like talking to old wrestlers or stuntmen. “I've probably broken the front knuckle on my left handâwhich constantly hits the edge of the snare drumâthirty or forty times,” said Andee Connors. “I'd split it open every show, and there'd be blood all over.” Over time he developed a large floating bone chip on his left index finger, which now restricts movement. A Minor Forest toured again in 2014, and after many shows, Andee posted on Facebook fresh pictures of that bloody and brutalized finger.

“I've got carpal tunnel in both wrists. I've got a pinched nerve in one elbow. My hands often go numb when we're playing,” said Mudhoney drummer Dan Peters, running down his list. Dan recently had his ears checked. It will surprise no one that the doctor told him to get hearing aids immediately. Another common drummer injury is epicondylitis, or tennis elbow, which can sometimes get so bad that it requires surgery, as it did for Six Finger Satellite's Rick Pelletier.

Rock has always been a contact sport. Patti Smith once broke her neck when she spun herself offstage. When Frank Zappa was in the Mothers of Invention, he was pushed into an orchestra pit, and broke his neck so badly that, at first, his bandmates thought he was dead. Imprecise pyrotechnics set Metallica's James Hetfield and Michael Jackson on fire. Our freak accidents were different. Void's extremely gymnastic singer, John Weiffenbach, destroyed his kneeâblew out his ACLâin the middle of one show, forcing a quick visit to an emergency room. David Yow made a habit of diving into the crowd, which didn't always work out so well. “My longest-lasting injuryâI call them by the city where they happenedâis my âSt. Louis,'” from the early nineties, he recalled. “I got thrown back on the stage by the crowd, and I couldn't catch my fall. I landed right on my spine, right about where your belt goes. The next day I could barely walk, and it's been a problem ever since.”

I know from experience it was a desire to transcend, as well as a fundamental masochism, that led us to dive into crowds and contort our bodies until they broke:

This is how crazy you, the audience, make me, and this is how far I will go for you.

So can we now, in middle age, learn how to perform in less joint-destroying ways? Not really. Though you knew your creaking body couldn't take much more, and you made so many promises to it, once it was showtime the old excitement kicked in, and like a weak ex-lover you went right back to

the exact same fucking thing

that hurt you. “Before you start playing, it just feels ridiculous and impossible that you will be jumping up and down at any point,” said Laura Ballance, whose knees are battered from doing just that. “But then it happens. You just can't help it.” She also has arthritis in her neck from headbanging her way through two decades of Superchunk shows. “I've been advised that I should not be doing that,” she said. “But I still do.”

Eventually, though, you just physically can't play anymore, or at least play in a way that you'd recognize. In 2013 I asked Roger Miller, when he was sixty-one, how much longer he thought Burma could keep going, given the limitations of the mortal frame. “You grow older and either you figure out a way to do it or you don't. If you sit at your computer, you get carpal tunnel. If you're a football player, you get concussions.” He shrugged. “And I'm not trying to be fatalistic or negative, but you're gonna die anyway.”

***

HERE IS WHERE I'M SUPPOSED TO SAY I'M SORRY. HERE IS WHERE

I'm supposed to say I realized, too late, that we should be careful with guitars and amps and drums and earbuds. Here is where I'm supposed to say we must

respect

the delicate tissue that makes sense of the sounds around us. Here is where I should beg everyone, in simpering and cloying tones, to

please

teach the children to learn from our mistakes.

Screw it. I don't regret a thing. Sure, I did some stupid stuff. (It doesn't sound so great when you stick your head into a bass drum.) But everyone who did equally stupid stuff was transported to places most people will never know. The old athlete walks tenderly on his aching knees. My ears ring. Andâalong with Mark Arm and Dan Peters and Laura Ballance and Andee Connors and Roger Miller and God knows how many moreâI can't hear anything you're saying in this noisy bar. But so what?

I ended up getting a relatively clean bill of health from the audiologist, though he found my left ear is weaker at picking up mid-range frequencies. Ear doctors sometimes call this a “noise notch,” because it often appears among those steadily exposed to loud sound. (For many years of practice and performance, that ear was closest to my amplifier.) I was told that my hearing against background noise was actually passable. Neither Laurel nor I believe this finding, for what it's worth, and Dr. Resnick later conceded that real-world conditions are impossible to simulate. Still, that's what his test showed.

Some months after my visit I called Dr. Resnick to interview him for an article in

The Atlantic

, and at the end of our conversation I asked him if he had worn earplugs when he was an active musician. “Ah,” he saidâand here he paused deliciouslyâ“more often than not, no. I found it a little difficult to wear them while performing, especially if you're doing any singing.”

I guess he'll understand, then, if we all keep treating our ears the way old drunks treat their livers, always wanting one last spree, always hoping, each time we play too loud, that they don't go kablooey. Because, really. We're just gonna

quit

?

When Bitch Magnet played our reunion show in San Francisco, Andee Connors lent us a speaker cabinet, and we met him at his practice space to grab it for soundcheck. As we drove up I saw him leaning against his truck, stooped over and plainly in pain. His back had gone out the day before, he told me. He has arthritis and related maladies, for which he blames his bad posture while drumming.

Andee's new band, ImPeRiLs, opened for us that night, and when I ran into him backstage, he was clearly still hurting, bent over and wincing. It hurt your own back just to see him. Once onstage, though, he was gleeful, grinning, beaming, joyful, looking years younger. As long as you're up there, you don't feel a thing.

A

Korean, a Mexican, and a Jew walked into a bar in Vancouver on a Saturday night in late October 2012, not far from the weekend shitshow of Gastown and the vacant-eyed junkies zombie-ing down Hastings, and, once the drinks were served, Sooyoung raised his glass. “I'm glad you guys talked me into this,” he said. Tomorrow we would play Seattle, the first night of our American tour. But I took him to mean the entire reunion adventure.

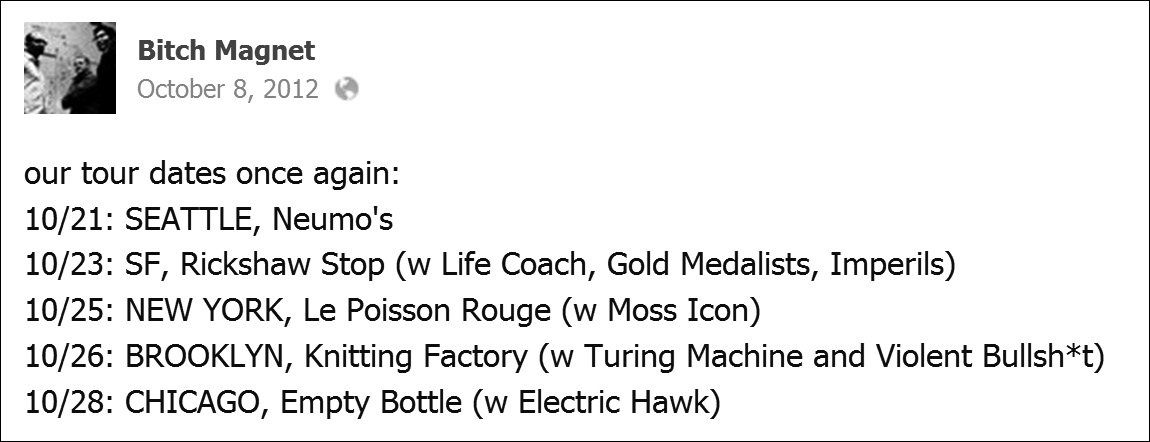

I always liked touring in the fall. Cooler, clear days, night coming on earlier, breaking out sweaters and heavier jackets for the first time since March. Once, October meant fall break and bombing eastward on Route 80 in a rattling old American car full of gear with Sooyoung, en route to play New York and Boston, talking all the way about the future and the band. Not this time. We knew, going in, that these shows would be the end. That was the key to selling them to Sooyoung. We crammed as many shows as we could into the time each of us could carve from his schedule, and since the dates wound up being in Seattle, San Francisco, Chicago, and two in New York, we had to fly to each one, as we had in Asia in April. Jimmy Page was really into how flying to each show injected urgency into touring, and you don't need to travel on your band's private jet to feel it, too. But I felt pangs of regret over losing one last time in the van and the sound of those tires turning on pavement, a music in itself, one long ago bound to

this

music in my mind.

There was symmetry and logic to ending the band after these shows in America, or there was once I got past the horrible, poignant, aching back-to-school-and-things-are-dying autumn-of-the-soul feeling I inevitably got at this time of year anyway, made worse by the looming conclusion to a very delayed extension of my early twenties. But I'd tired of the logistics and persuasion required to make it all happen: mapping itineraries, arranging transport and lodging, dealing with promoters and equipment rental. I'd tired of the complications associated with disappearing from work for long stretches. I'd tired of how crazy the run-ups to touring were and how harsh the rock hangovers were afterward and the effects my mood swings had on the people around me. I'd even tired of a couple of the songs in our set. (Though only a couple.)

After years and years of living with barely any structure at all, I'd discovered that the routines of marriage and adult life were strangely comforting, but there was little template for what would happen on the road, and that chaosâthe sheer density of events jammed into such a short stretch of timeâwas still so seductive. The foreknowledge of each approaching tour took up much mental space, tugged at me endlessly, and could never be properly explained to civilians. And describing the musician's transition to normal life, once the touring is over, was even harder. “I don't mean to make light, but I really would liken it to a soldier in active duty coming home,” Rick Pelletier of Six Finger Satellite said. “Suddenly you're a civilian. You have to act excited when you're going out to dinner with friends.” Even though you're used to much stronger stuff at night.

Peter Mengede, who played guitar in Helmet and Handsome, portrayed homecoming in even starker terms: “You find yourself without that thing that you've been focused on, that you looked forward to, that you found satisfaction in, that got rid of all the horrible, ugly stuff inside you. All of a sudden you're sitting at home. No band. Nothing to do and nowhere to go. It's time to grow up and retrain yourself. Try to find a way into the real world. But then, once you do get in the real world, it is fucking boring. The work thing, apart from the moneyâit's absolutely pointless. I've got a band now. It's minor leagues. But it gives me something to do. Without that it would just be suburbs. It would just be fucking shopping malls, and getting on the train with all these fucking diabetics going out to buy a flat screen or Kentucky Fried.”

The night after I returned from touring Europe in December 2011, I dragged my reluctant and severely sleep-deprived carcass to a work-related event in a landmark building uptown. I didn't want to go, but I thought,

I have to get back to normal life

. Even though the other life was still so present: severe fatigue, ringing ears, the sensations from the crowds and volume fading only slightly after traveling those thousands of miles. I walked in, confused from jetlag and feeling very out of place beneath the carved and gilded ceilings, so intricate that in my addled state they made me think of looking up at the circuitry underneath the spaceship in

Close Encounters

. I grabbed a glass of wine off the first waiter's tray I saw, tried to focus, ran into someone I knew, and casually asked what's up. This person went into an excruciatingly detailed description of a something-something and then went into an equally colonoscopic analysis of a deal that something-something was considering. You know how you find yourself in a conversation and try to find the polite way to end it, or see someone over a person's shoulder so you can disappear as quickly as possible, but can't? That. The ennui and jetlag made me feel weightless. I looked up and imagined myself floating above this dazzling room. Quite a setting, this. Real nineteenth-century robber baron shit. Old-money eccentric, incredibly ornate, even slightly deranged in its details. Everyone else here seemed so happy. But it was just people walking around. Some rock-damaged circuit in my brain kept asking,

This is it?

I was both bored and overmatched, feeling like I understood nothing outside the ritual of driving and load-in and setup and soundcheck, the tension of waiting for the venue to fill and the relief when it did, slowly at first and then very quickly. But this event, tonight? What was the point?

The people around me were good people, but they had no idea how wrung out I felt, how my head was still slightly blown off, how that feeling was fading, and while I knew far too well that it was a crazy and unsustainable way to live, especially now, I was still desperate to fan its dying embers. That I was slowly waking up from the dream, and the contours of everyday life were only starting to come into focus. The closeted husband can't talk about his boy toy downtown. The functional junkie doesn't tell co-workers about his weekend nodding off in a motel room amid needles and spoons and people he would normally never see in daylight. Those guys can only share those things with others who've been there themselves. There was no one like that here this night. Or on most other nights.

Sometimes at a work-related gathering it comes out that I've played in bands for over twenty years, and that one of them recently reunited to perform in Europe and Asia and America. And necks inevitably straighten and heads tilt, and a fiftyish fund manager or lawyer or media executive or management consultant will ask the name of that band, and sometimes, as soon as I say “Bitch Magnet,” the gravity shifts, and any power of being this specimenâan actual rock musician who actually toured and put out actual records and CDs, back when people actually did that!âdiminishes. You see it register, and then see mirth.

This is what it sounds like:

What?

Oh.

Oh! Ohhhh! Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha. Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha!

Bitch Magnet?

Bitch? Magnet?

Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha! Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha!!

After all these years of playing music, and as a grown man now myself, I understand this reaction. Bitch Magnet is kind of a silly name! But the person who laughs isn't laughing like a pal who had

also

been a teenage punk rocker and, as such, laughs from knowing. This person who laughs doesn't understand. This person who laughs is laughing becauseâbrieflyâthis person feels superior. In Passover seder terms, this is the son who doesn't even know how to ask a question:

What is this?

As such, the Haggadah instructs us, he should be treated with patience.

But sometimes I feel like, enough already. And what I want to do more than anything is smile through my anger, maybe chuckling a little bit myselfâ

Heh heh heh heh hehâ

then say to the person who laughs:

I wish you'd seen, and heard, the amazing things I did because I was in bands.

I wish you'd seen, and heard, the amazing things I did because I spent all those years in punk rock clubs.

I'm sorry you never had a moment in which the dim candle flare of discovery suddenly became apparent to a few musicians locked away from the rest of the world in a soundproofed practice studio. Or a moment like the ones I glimpsed alone, at home in my tiny studio apartment in 1993 or 1994, kneeling on the carpet next to my 4-trackâits red

RECORD

light blazingâsinging quietly so the neighbors couldn't hear, into a microphone clutched hard in both hands, suddenly dead certain, after groping blindly for hours, that I'd picked the lock and stepped through a doorway to a moment of pure glory.

I wish, at least once, you'd known how it felt when people pulled you aside urgently to tell you how much they loved your records. I wish you knew what it was like to stumble on a stage, stoned with exhaustion, congested and sluggish and woozy from a mid-tour flu, and then feel some switch flip, and take you from earthbound to flying. I wish you'd been there and we'd run around together in our little undergroundâpunk rock or indie rock or whatever we called itâbecause it was, you should know, one of the more important cultural movements to happen in your lifetime.

It's clear, though, you weren't there, because you're laughing about

a fucking band name.

That's why, laughing guy, we need to leave this party or dinner right now, rush back to my apartment, flick on the lights, fire up a computer . . . No. To

really

do this, I have to dig through boxes of old flyers and tour itineraries and clippings from music magazines that no longer exist, and fanzines made with the jarring look and terrible fonts from the earliest days of what was then called desktop publishing. And tell you about Wire and Stooges and This Heat and Mission of Burma. Wipers and Sleepers and Swans. About Melvins and Void and Green River and Meat Puppets, and how Black Flag got even better once they slowed down. Naked Raygun and feedtime and High Rise, and Laughing Hyenas and Scrawl. Die Kreuzen and Squirrel Bait and Honor Role. Drunks with Guns and My Dad Is Dead. Glenn Branca and Smashchords and Gore. About seeing Butthole Surfers and Boredoms and Suckdog and Caroliner, and Pavement with their first drummer and Live Skull with their last singer. Watching Sonic Youth on

Night Music

in 1989, and the Minutemen on MTV in 1985. About college radio and record stores, and how fanzine editors were either the quietest or most annoying people in town. About finding original Electro-Harmonix pedals and Moog synths and Travis Bean guitars, and Orange or Hiwatt or Ampeg amps long before eBay made all their prices skyrocket, thanks in part to how we sought them out and talked them up. Drinking at the Rainbow and Max Fish. Combing through the new-arrivals bin at Pier Platters and Oar Folk and Reckless and Olsson's and Newbury Comics and Fallout and Aquarius and Amoeba and Wuxtry, and scanning the racks of fanzines at See Hear. About Homestead and SST and Touch and Go and Sub Pop and Drag City and Matador, of course, but also Amphetamine Reptile and Neutral and Rabid Cat and Treehouse and Ruthless and Reflex and 99 and Ecstatic Peace.

But whatever you do, laughing guy, please don't start talking about your cousin who

plays in a band, too!

if that means he plays classic rock covers in a bar sometimes, or in a “blues” band that performs in the gazebo in a town square once every summer. I don't really expect you to know that we invented our music to destroy that stuff. But I'd still rather chop off a finger than take you up on your offer to introduce us so we can jam sometime.

And allow me to make this one nagging and exquisitely subtle point: your cousin and I

do

have a few things in common, having both spent time on the lowest rungs of the music business, a truth I cannot escape even if I believe in my aesthetic and spent my entire adult life scorning his.

And, yes, since you asked, you can find my band on Spotify and Pandora and iTunes and Amazon and YouTube.

Oh, and one last thing?

Fuck you.

***

IN 1998, WHEN I WAS THIRTY AND BROKE, A GOOD FRIEND GOT

married in Manhattan, at the kind of wedding romantics call

magical

: the vows were exchanged at the Church of the Ascension on lower Fifth Avenue, and the reception was held in a gilded space nearby, where a few of us music freaks found each other. Though all the men wore suits and ties and all the women looked ravishing in evening dresses, we could still smell the subculture on each other.

One of us seemed slightly more off than the others: older than the rest of us, tall, quiet, wearing institutional glasses and an ill-fitting suit, awkward-looking in an almost alarming way. His name was Ray. Somehow the subject of high school came up, and awkward Ray started talking.

“Man, I was the uncoolest kid in my high school,” he began, and I immediately and uncharitably thought,

Yeah, we could tell

. But, he continued, after high school he joined a band, which toured and put out some records, and after years of that he finally thought he might be, at last, sort of cool. He attended a high school reunion, believing this music thing would make him less outcast. “But,” he concluded, “you know what? No one cared. They all still thought I was the biggest loser there.” Nods of agreement and murmurs of sympathy all around. I broke the subsequent silence by asking, “Hey, Ray, what was the name of your band?”

And Ray answered, “I was in a band called the Dead Kennedys.”

Holy shit! We're talking to East Bay Ray!

I told him that if we'd had this conversation when I was sixteen, I would have just peed my pants. But set that aside, because no matter that you think what you're doing with your band is the coolest thing in the world, no matter, Ray, that you are a founding member of

one of the biggest and most important punk rock bands ever

âthe straight world will never understand a thing about it. Or care. As the world will be quick to remind you, should you ever fail to remember.