Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders (37 page)

Read Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders Online

Authors: Srinivasan S. Pillay

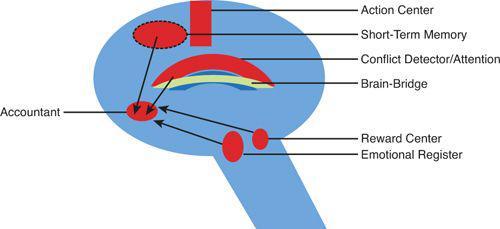

Thus, from conflict resolution to job performance, understanding emotions and how to apply this understanding meaningfully may significantly enhance business productivity. The remainder of this section discusses several emotional regulation interventions. The diagram below illustrates the targets for emotional regulation.

Figure 8.1. Targets for emotional regulation

DLPFC (Short-Term Memory) Intervention

Emphasize recent events. When emotions are overwhelming because there is a seemingly endless timeline to the distress, you can bring a person “into the moment” to reduce the emotional burden. A lawyer with whom I worked had a large law practice and several paralegal assistants. However, when one paralegal assistant left on maternity leave, her work fell to the other paralegal, who was enraged. The lawyer could not afford to hire another person and needed to save the money because business had been reduced. In effect, the other paralegal had one-and-a-half times the work she had had before. She was overwhelmed by having to do this much work for three months; however, when the lawyer reassured her that they would look at things a week at a time, she was able to calm down significantly.

MPFC (Accountant) Intervention

Introduce risk-reward calculations and change the timeframe to a long-term perspective. Here, we do the opposite of the previous intervention. When a person is feeling overwhelmingly anxious, the PAG may be activated (with spillover from the vmPFC). Imminent threat leads to uncontrollable anxiety. Thus, you should strive to make

the threat less imminent. Also, the vmPFC is involved in empathy. It may be useful to shift the person out of the empathic state and into one of having a cognitive perspective. For example, an M&A specialist from one company was hired to work with the joining company as they explored the “fit.” The joining company had much unbridled emotion about how things “used to be done.” In this case, rather than coming up with an entirely new method that was forced upon the joining company, I recommended that the M&A specialist ask the following questions: “What worked with the previous approach? What did not work?” This brought in the risks and rewards explicitly. Then, I recommended trying to “understand” the insistent emotion rather than internalizing it. This changed the M&A specialist’s approach from “There’s no need to get so excited” to “I see that you really value the way things used to be done. Although we run our labs very differently, we would love to employ what really worked for you. If you had to make a trade-off....”

In this case, not taking in or judging the emotion and acknowledging the fear of lost value was a cognitive perspective that worked well.

ACC (Attention Monitor) Intervention: SAFE-Frame

We can use ACC interventions to access the amygdala as follows:

• Resolve conflicts. This will help to decrease emotional intrusions.

• Reengage people at all levels of the company (in other words, distribute responsibility).

• Refocus on the positive (or elsewhere). Focusing on the threat makes the threat even worse (ACC studies show us this).

• Reassess by decreasing catastrophizing.

• Reframe by using a multiple redefinition technique. Explore the other perspectives of the situation causing the immense anxiety. For example, a CEO who was overwhelmed by his R&D budget being cut in half spent all of his time fretting over not being able to innovate the way he used to because of having diminished resources. When I asked him, “What new doors open during a recession?” he looked blankly at me. However, after he thought

about this, and the fact that he was not alone, it led him to recognize that he could join forces with other people and share the budget and profits for his new technology ventures.

Corpus Callosum (Brain-Bridge) Intervention

The brain-bridge connects the left and right hemispheres of the brain. Thinking and feeling coexist optimally when the brain-bridge is functioning well. Worry is associated with brain-bridge disruptions, and a useful question to ask here is, what is worry serving? Very often, worry, especially when it is based on a legitimate reason, serves as an excuse to avoid a deeper fear—often the fear of failure. People now have a “valid” excuse not to succeed. In the business setting, employees may worry because this gives them a sense of control (by having something to worry about) rather than dealing with their free-floating anxiety. This often shows up in people who are overly concerned about “the bottom line.” They may focus on the bottom line and then create angst by tying all actions to the goal while ignoring the feelings of the people who are executing this goal (and their own feelings as well).

Brain-bridge disruptions cause a delay in feelings becoming part of the equation. To expedite this connection, you may ask, “When you think about that, how does it make you feel?” or “When you feel like this, what could make you feel better?”

Motor (Action) Intervention

You can recommend going for a walk or institute an exercise program at work (for people medically cleared to participate). This can significantly improve emotional control because movement can stimulate new thoughts.

18

,

19

What used to be considered just a “movement” center only is now considered critical for many other functions, including imagery. In the chapters on change, we saw how you can use first-person imagery that you believe outside of a stressful state to activate the motor cortex. When dealing with emotional challenges,

you can ask employees to train themselves to have imagery consistent with their goals. This quiets down emotional dysregulation.

Reward (Basal Ganglia) Intervention

You can point out potential social and financial rewards when anxiety is low enough. When anxiety is high, rewards are not registered. The first priority is to lower the anxiety (or loneliness) prior to discussing rewards. Without reward, there is little motivation. The reward center of the brain needs to send the correct information to the brain’s accountant (vmPFC). Simply delineating the rewards of a planned action does not work. You first have to use amygdala and ACC interventions to diminish anxiety. Also, people cannot imagine rewards when they feel stress, and stress diminishes the imagery-related brain activations. Knowing this can empower managers to use reward-based motivations appropriately.

Amygdala Intervention

Replace anxiety with optimistic imagination questions: “If things had been different, what would you have wished this outcome could be?” Optimism will displace fear from the amygdala. Remember not to frame optimism as a cheerleading approach, but rather as a way to allow the brain to keep a possibility alive and search for solutions. Also, developing trust can decrease amygdala activation, so this would be a useful thing to do if fear and anxiety are the issues.

Hence, much like the approach to having a difficult conversation (from earlier in the chapter), this intervention involves walking the leader through his or her own coping mechanisms (in actuality) by targeting each one as described previously. This increases confidence, and when done in an engaging manner, will help managers, leaders, and employees feel more empowered emotionally.

An Approach to Managing Cognitive Flexibility

Flexibility in thinking is a significant ability to have, especially in rapidly changing business environments.

In a volatile economic atmosphere, having flexibility built in to a way of thinking can be really helpful. When people are wedded to their own ideas without being responsive to change, this inflexibility can ignore fundamentally important changes, such as changes in demand for a product or service.

20

With fast-changing business conditions, the ability to be cognitively flexible is critical to ongoing learning and adaptation.

21

Otherwise, employees will feel like square pegs in round holes.

Flexibility in thinking is crucial for risk-management skills, especially during corporate crises.

22

Flexibility in thinking and business strategy is also key for transnational leaders who work across different continents and cultures.

23

Thus, from transnational leadership to adapting to changes within a single company, understanding how to accentuate cognitive flexibility is very relevant and important.

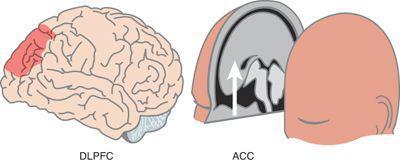

When thinking about cognitive flexibility interventions, keep in mind that the brain circuits that underlie flexibility in thinking are the ACC and the DLPFC, as shown in

Figure 8.2

.

Figure 8.2. The DLPFC and ACC

One of the core components of dealing with crises involves switching tasks effectively. The ACC arranges the priorities of the new task, and the DLPFC tackles interference from the old tasks so that leaders will not just use old methods to solve new problems.

24

You can help the DLPFC by spelling out what you expect to interfere from past methods. Stress perpetuates habit memories. When working with someone who is using an entirely new way of doing something, ensure that his or her stress level is manageable or the new way won’t be employed.

A manager with whom I worked decided to manage his business by simultaneously adopting new ways of recordkeeping with a very high degree of auditing. This escalated the anxiety in the company, and the goal of increasing efficiency was not achieved. Once he used a more emotionally intelligent approach of not pressuring people but teaching them, people switched over to the new methods much more easily. Change is very anxiety provoking in the business environment. That is why it is so challenging—the amygdala disrupts ACC functioning, and this internal conflict manifests in decreased productivity.

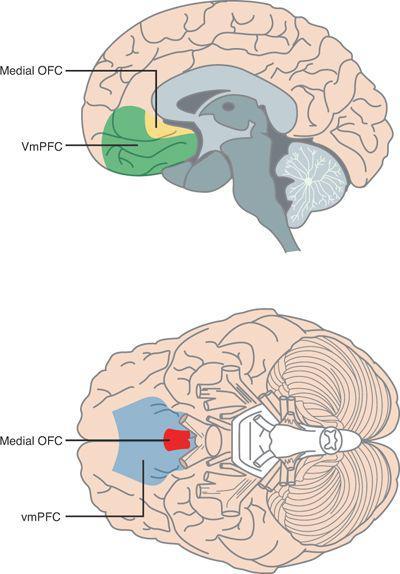

Also, experiments in cognitive flexibility have tested reversal learning, where subjects must first learn to pick, for example, a black object among white objects and then have to learn to do the opposite. The OFC (related to the vmPFC, as shown in

Figure 8.3

) is critical in this function. From animals studies it appears that the OFC is not needed when task experience has been gained, but it is necessary when task demands are relatively high.

25

Other brain regions (basal ganglia and posterior parietal cortex) may also be involved.

26

Figure 8.3. The brain regions involved in cognitive flexibility

The ventromedial prefrontal cortex and medial orbitofrontal cortex, if damaged, result in decision-making deficits. It is therefore prudent to advise people that new approaches use more “brain energy” because there is a lot of conscious brain processing (by the OFC). However, after learning has taken place, the actions are more automatic and therefore less energy draining.