Zombie CSU (6 page)

Once the 911 call has been made, the central dispatch will contact the specific unit whose patrol route covers that location. “In rural counties,” Brennan says, “one dispatch center is often used for all of the surrounding towns. Computers and radio reports track the general movement of available units. If the car that would normally respond is handling another complaint, at lunch, doing transport or any of the thousand other jobs that police officers routinely handle, then the request for responding units is broadened. In very serious crimes this might result in units responding from several neighboring towns.”

For violent crimes, like the one reported here, and one where the suspect is believed to still be at large, a fair number of cars would roll.

According to Greg Dagnan, CSI/Police/Investigations Faculty—Criminal Justice Department, Missouri Southern State University, “The dispatcher will keep the caller on the phone while emergency responders are in route. This process also encourages the caller not to hang up in case police can’t find them or some other unexpected event occurs. Police are usually the first to enter a scene like this even if others (fireman, ambulance) beat them there. Police must ensure that responders will be safe while lifesaving measures are performed.”

911 operator Fredericka Lawrence adds, “The constant contact between operator and witness not only saves lives, but it keeps the witness on the scene, which means that the officers and detectives will have someone they can interview. That speeds up the entire process.”

The Zombie Factor

The scenario we’re using to make our examination of the zombie outbreak is one seldom ever shown in the films. We’re working with the actual

patient zero

, the central or “initial infected person” in an epidemiological investigation. If patient zero is stopped in time, then there will be no plague to spread; if he’s stopped too late, then every person he bites becomes a potential disease vector.

The good news is that in the real world these things often start small. One zombie out there and a whole police force against it, with all the might and technological resources that can be called to bear, should be able to do the trick. It would be less dangerous than, say, a group of hunters trying to subdue an escaped lion or tiger. Dangerous, yes, but doable.

The bad news is that the zombie has to be seen and identified as a disease-carrying hostile vector. That’s not going to happen quickly or easily, and probably not at all during this phase. Diseases are invisible, so the police will likely react as if the assailant is either mentally unstable or whacked out on drugs. Or both. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, because suspects demonstrating odd and irrational behavior are treated as if they are very dangerous. Extra caution is used, more backup is called, and greater safety protocols are put in place. On the level of one (or at most a few) of the slow, shuffling zombies, the police department is more than ready to meet the challenge.

In our scenario, our witness has seen a strange and apparently drunk or stoned individual attack someone else and then stagger off in to the woods across the street. We don’t yet know why the zombie fled leaving a victim still alive. We don’t know if the sight of the witnesses’s car, or the smell of its engine frightened off the zombie. Can we even use the word

frighten

in connection with zombies?

1

We don’t know if something attracted it; or perhaps

called

it. All we know, based on the eyewitness’s testimony, is that the zombie attacker has fled.

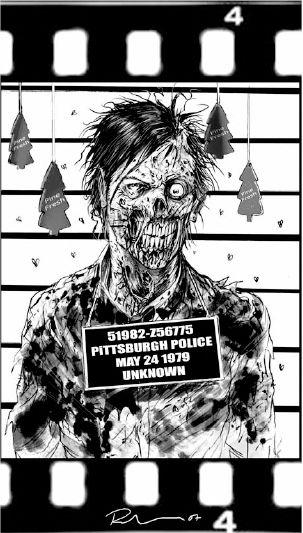

Art of the Dead—Rob McCallum

Patient Zero

“I’m old school so prefer my zombies to be slow. The fast ones are pretty scary too but I just don’t see dead bodies being able to run for too long before bits of them start to give out and fall off!”

The novels

The Rising

and

City of the Dead

by Brian Keene,

2

Dead City

by Joe McKinney,

Dying 2 Live

by Kim Paffenroth, and

The Cell

by Stephen King explore the possibility that some other force, being, or hive consciousness was able to control large groups of zombies. In

Land of the Dead

the chief ghoul, Big Daddy, seems capable of directing the actions of his fellow “stenches.” However in Romero’s original zombie films,

Night, Dawn,

and

Day,

the zombies were antonymous, their actions being directed by whatever constituted their postresurrection set of instincts. As such (and although they do seem to gather wherever one or more humans are hiding), they do not appear in any way organized, any more than flies are organized even though masses of them gather around a corpse. Even if we grant a certain degree of unpredictability due to the police initially having insufficient evidence, we are still looking at a situation in which the suspect will not be actively hiding (and will, by nature of its reduced intelligence, be incapable of this), and a suspect who will take no effort to prevent the leaving of evidence. There will be a lot of evidence to collect—fingerprints, footprints, blood spatter, trace DNA, witnesses, possible video surveillance from the location of the attack, and more. Once the police and crime scene unit arrives and the evidence collection begins, the hunt for our undead suspect will begin in earnest.

Help is on the way.

J

UST THE

F

ACTS

First Responders

A crime scene is a tricky thing. It seldom has clear boundaries like you see on TV. In some cases the crime scene expands to include the planning and staging areas, the routes taken to and from the “primary scene,” and even a recovered vehicle associated with the crime. Clues and evidence may be found at any or all of these.

The primary scene, however, is where the real action takes place. (For us it’s the research center on Argento Road in Romero Township.)

The first police unit to arrive at a crime scene has a lot of responsibilities to handle, and even a two-officer car will be kept very busy. As the first responder unit rolls up, the officers have to assume that the situation is still active and dangerous. Assuming otherwise could be highly dangerous to everyone involved. Just because a witness says that the assailant has left, that doesn’t make it so. And there is the consideration of the wounded victim. All of this is in their minds as they pull up to the scene.

But their first task is to observe the situation, noting the physical layout, the presence of objects (buildings, trees, vehicles, etc.) that could provide cover for a suspect or limit their assessment of the scene. They have to note whether any vehicles or persons are entering or leaving the scene. This includes identifying the presence of all persons (living or dead) and making very quick judgments about each person: Are they stationary or fleeing? Are they injured or dead? Are they actively engaged in a struggle? Are they lucid, raging, crying, etc.?

The first responders have to locate the scene, which isn’t always as easy as it sounds. Witnesses, especially phone-in callers, are seldom clear and concise, and these callers may be unfamiliar with the location of the incident. Once they find the right spot, they have to secure the scene to prevent contamination of evidence. Much will depend on how well the first responders handle this.

As the officers get out of their unit, they have a chance to take sensory impressions of the scene. What do they hear? What do they see? What do they smell? Often these first impressions are crucial to the development of an effective investigation of the crime.

If the suspect is in view, he needs to be contained and detained, then cuffed and placed in the back of one of the responding vehicles.

The officers have to locate and assess the victims. Backup and ambulances are typically called at this point, even before the officer gets out of his car. In our scenario the victim is comatose and badly injured with what looks like bite wounds and other lacerations. While waiting for this, the officers provide any necessary first aid the situation requires. Police officers are trained to do this and, sadly, very often have way too many opportunities to practice it. Prophylactic measures, such as latex gloves, are now standard for most police departments in the United States, which significantly reduces the risk of infection from welling blood and open wounds. In zombie attacks, of course, first aid can get dicey, since the infection rate from fluid exchange is estimated at 100 percent.

Zombie Films You Never Heard Of (but Need to See)—Part 2

The Happiness of the Katakuris

The Happiness of the Katakuris

(2000): A Japanese zombie musical. Weird, not very well done but absolutely watchable if alcohol is involved. I, Zombie: A Chronicle of Pain

I, Zombie: A Chronicle of Pain

(1998): Granted, it’s pretentious, but it’s clear some real thought went into this British zom film. Give it a chance. Io Zombo, Tu Zombi, Lei Zomba

Io Zombo, Tu Zombi, Lei Zomba

(1979): An Italian zom com with a witty sense of humor. Very hard to find, but worth it. Kung Fu Zombie

Kung Fu Zombie

(1981): Hilarious Hong Kong zombie comedy. The plot doesn’t make much sense, but you’re laughing too hard to care. Let’s Scare Jessica to Death

Let’s Scare Jessica to Death

(1971): A true “lost classic” that deserves to be found and watched. Creepy, subtle, and nicely twisted. The Living Dead at the Manchester Morgue

The Living Dead at the Manchester Morgue

(1974): Also known as

Let Sleeping Corpses Lie

, this one has the makings but never quite found its audience. Dig up a copy. The Living Dead Girl

The Living Dead Girl

(1982): There’s a good argument on both sides as to whether this is a zombie flick or a vampire flick; either way it’s an interesting study into addiction, codependency, need, and love.