100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die (7 page)

Read 100 Things Dodgers Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die Online

Authors: Jon Weisman

13. Family Affair

One was as tough a cuss as you'd find on the mound, a rough-and-tumble warden of the strike zone who'd knock you down if you so much as breathed on his part of the territory. “I hate all hitters,” he said. “I start a game mad and stay that way until it's over.⦠If they knocked two of your guys down, I'd get four.”

The other had the carriage of a professor. He was nicknamed “Bulldog” to coax the he-means-business side of his personality, but even when that succeeded, the moniker retained its irony when juxtaposed with the man.

Don Drysdale and Orel Hershiser were heroes of a different stripe, at least if you buy into the mythology. By their reputations, you wouldn't assume they'd necessarily get along. But when Hershiser broke Drysdale's major league record for consecutive scoreless innings, the Dodger world saw how sincere a bond had formed between them.

“Where is Drysdale? I've got to find Drysdale,” Hershiser said, according to Bill Plaschke of the

Los Angeles Times

, upon reaching the dugout moments after completing his 59

th

goose egg in a row. “It couldn't happen to a better kid,” Drysdale, who had become a Dodger announcer, told Hershiser after they embraced.

“At least it stays in the family,” the older pitcher added.

It was Drysdale, the Van Nuys native, who in 1968 brought the record home. He was 31 years old, but already in his twilight as a ballplayer. His left-handed complement, Sandy Koufax, had retired at the end of the 1966 season at 30, and the Dodgers had since plunged from the World Series into losing more games than they were winning. Drysdale himself had barely a year left before his own retirement when he threw a two-hit shutout against the Cubs on May 14.

Two blankings of Houston sandwiched one of St. Louis, and by the end of the month, Carl Hubbell's 35-year-old NL record of 46

1/3

consecutive scoreless innings was coming in sight. Famously, in the ninth inning against the San Francisco descendants of Hubbell's New York Giants on May 31, Drysdale lost the streakâthen regained it. Perhaps it would have been an appropriate touch for Drysdale's streak to end on a hit batter such as the Giants' Dick Dietz. But as the bases full of Giants began their advance, umpire Harry Wendelstedt ruled the pitch a ball on the grounds that Dietz hadn't tried enough to avoid it, thus making the count 3â2. Dietz then flied out to left, and two more edge-of-your-seat outs later, Drysdale's streak was at 45.

Drysdale broke Hubbell's record June 4 against Pittsburgh during his sixth straight shutoutâa feat Robert F. Kennedy would mention hours later in the opening of his California Democratic Primary victory speech at the Ambassador Hotel, moments before his assassination. Drysdale was primed to pass Walter Johnson's major league record of 56 against Philadelphia in four days.

As Dan Hafner of the

Times

noted, Drysdale began with seven balls in his first eight pitches. But he settled down long enough to get a 1â2â3 second inning to tie Johnson, then retired shortstop Roberto Pena and, after a single by Larry Jackson, struck out Cookie Rojas and Johnny Briggs to make it 57.

At the end of that inning, upon the request of Phillies manager Gene Mauch who suspected a foreign substance in play, Drysdale was warned by umpire Augie Donatelli not to touch the back of his head for the rest of the game. Howie Bedell broke the streakâat 58

2/3

inningsâin the fifth inning with a sacrifice fly, though Drysdale denied that the warning was the reason.

“I wanted the record so badly,” he said, “but I'm relieved that it's over. I could feel myself go âblah' when the run scored. I just let down completely. I'm sure it was the mental strain.”

Drysdale retired with a 2.95 career ERA (121 ERA+) and 2,486 strikeouts in 3,432 innings, and most assumed that the scoreless inning streakâreduced officially to a fraction-free 58 inningsâretired with him. But then came the tall, reedy Hershiser, whose first full season was 1984, the year the Hall of Fame inducted Drysdale.

Hershiser hinted at his record-setting potential by unfurling 33

2/3

consecutive scoreless innings in the summer of '84 and established himself as a frontline pitcher with a 2.03 ERA (170 ERA+) the following year. But that didn't mean his run in 1988 was anything less than stunning.

It began with four shutout innings after allowing two runs in the fifth to Montreal on August 30. Five shutouts later, thanks in part to another favorable umpire ruling for the Dodgers against the Giantsâan interference call on sliding Giant Brett Butler that nullified a Jose Uribe run in inning 43âthe streak was at 49 innings, exactly one shutout away from Drysdale's official record of 58. And Hershiser had only one start remaining in the regular season.

There was talk about Hershiser sneaking in a relief appearance if he needed a chance to break the tie, but the Dodgers offense paid homage to the era Drysdale pitched in by simplifying matters to match Hershiser zero for zero on September 28 at San Diego. With two out in the ninth inning of the scoreless game, the Padres' Carmelo Martinez grounded out to give Hershiser a tie for the record.

“I really didn't want to break it,” Hershiser told Plaschke. “I wanted to stop at 58. I wanted me and Don to be together at the top. But the higher sources [Lasorda and Perranoski] told me they weren't taking me out of the game, so I figured, what the heck, I might as well get the guy out.”

Drysdale, always the competitive type, laughed when told of Hershiser's statement. “I'd have kicked him right in the rear if I'd have known that,” Drysdale said. “I'd have told him to get his buns out there and get them.”

It wasn't automatic. Hershiser struck out Marvell Wynne, but with a wild pitch that allowed him to reach first base. Two outs later, there were runners at second and third. But Keith Moreland flied to Jose Gonzalez in right field, and the record was Hershiser's.

Though he would later allow runs in the ninth inning of his next game in the NL Championship Series as well as his first regular season inning of 1989, Hershiser's record season was even more memorable than Drysdale's. Counting the 42

2/3

innings he pitched in the '88 postseason, including NLCS- and World Series-clinching victories, Hershiser ended the year by allowing five earned runs in 101

2/3

innings, a 0.44 ERA in the most pressure-packed situations.

Like Drysdale, Hershiser began to have arm trouble not long after the streak, though he stretched out his career all the way to 2000, retiring at age 42 with a 3.89 ERA (112 ERA+) and 2,014 strikeouts in 3,130

1/3

innings. Hershiser won't make the Hall, but he'll remain a legend. And the record is safeâfor now, though the humble Hershiser isn't holding his breath.

“I never thought I would break this record,” Hershiser told Sam McManis of the

Times

. “I thought nobody would break this record. But now, I think somebody can break it from me, because I'm nobody special.”

Â

Â

Â

14. Hall of Fame Businessman

In early 1958, Walter O'Malley started talking about his passion for baseball, but he just as easily could have been talking about business.

“It's a virus, my boy,” he told Robert Shaplen of

Sports Illustrated

. “Baseball is in my Irish bloodstream and I revel in it. Dr. Salk hasn't found a vaccine for it yet, and I'm glad.”

O'Malley loved the game as a child (like Vin Scully, he was raised a New York Giants fan), but if he ever pictured himself in one of those Mayday situationsâbases loaded, two out, 3â2 count, the whole world watching, the fans living and dying with every pitchâhe was dead on, except that it would all be metaphor. He would be the owner, playing a game of exponentially higher stakes. He wouldn't win every game, but you don't win every game. It's a long season, measured not in days or weeks but years. You play to be on top at the end, and on top is where O'Malley finished.

By the time he attended the Culver Military Academy in Indiana and couldn't crack the varsity as a first baseman, O'Malley's feats of academia began surpassing his athleticsâultimately, he would become something of a five-tool coat-and-tie. As his official biography at Walteromalley.com notes, he was named senior class salutatorian and outstanding student at Penn, then earned his law degree at Fordham. In between, he wrote a widely circulated legal guide to New York Building Codes and established first a drilling company and then a surveying company.

Â

Â

Â

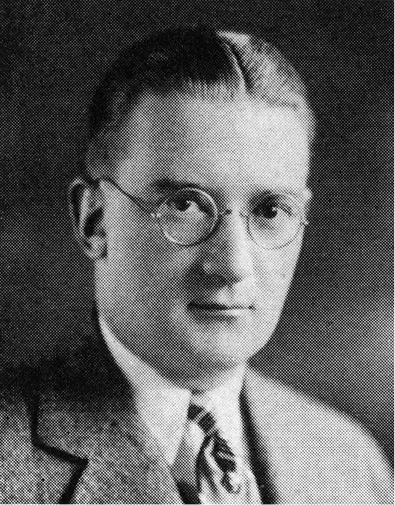

Walter O'Malley, future Hall of Fame owner of the Dodgers, received the highest honor of his University of Pennsylvania graduating class in 1926, when he was named “Spoon Man” as the outstanding overall student.

Photo from the Collections of the University of Pennsylvania Archives. All rights reserved.

Â

When he began to practice law in the post-Depression era of the 1930s, his focus gravitated toward business reorganizations and financing. That's when baseball and business began to meld into a single playing field for O'Malley.

“I had season seats at Ebbets Field,” O'Malley would later recall in a KFI radio interview, “and I found that that was a great way of entertaining clients, active or potential. I used my seats quite effectively for that purpose. It became pretty generally known that you could find Walter O'Malley at a Dodger ballgame in Ebbets Field almost each night. [That] led [to] my active association with the ballclub. I represented the Brooklyn Trust Company; the bank was a trustee of 50 percent of the Dodgers' stock. The ballclub was badly involved in a mortgage they could not pay off, and the president of the bank assigned me as a troubleshooter to step into the picture and see what could be done.”

Â

Â

Â

“The First Lady of the Dodgers” Kay O'Malley was honored by her husband Walter to toss the ceremonial first pitch at Opening Day of Dodger Stadium on April 10, 1962. Standing by her side was son Peter O'Malley, who later became Dodgers president in 1970.

Photo courtesy of www.walteromalley.com. All rights reserved.

Â

Though his professional interests would further diversify for the next 10 years, O'Malley would become more than a fringe major leaguer, joining the Dodgers wholeheartedly in 1943 as vice president and general counsel before becoming a co-owner inside of two years. In 1950, when he became majority owner of the team, he had been a part of the team's life and guiding it through difficulties for more than a decade.

As owner, O'Malley studied the game, worked doggedly, and played to win. His effort to keep the team in Brooklyn is well-chronicled and undeniable, but aging Ebbets Field was a pitch he ultimately couldn't drive. Like a savvy hitter, O'Malley went the other way for a hit, and smacked an opposite-country home run.

It wasn't that he had invented the notion of moving to the West Coast. It was inevitable that the major leagues would take up residence there. What wasn't inevitable was that it would be done well. In Los Angeles, he built the finest stadium and the finest franchise in the National League. From 1958 to 1978, the year before his passing at age 75, no team in baseball was more successful: seven NL pennants and three World Series titles. The organization averaged 89 victories per year and became a role model in baseball, epitomizing excellence while remaining family-friendly in price and atmosphere. As great as the team was in Brooklyn, it became greater in Los Angeles.

You can choose to care about one part more than another, but the game of Major League Baseball is inseparable from its business. Achievements in each arena matter. O'Malley wasn't perfect, but baseball isn't an endeavor that allows perfection. What Walter O'Malley was, though, was a baseball man par excellence and a champion of his game. That's why he's in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Â

Â

Danny Goodman

Dodgers fans of a certain age will remember Danny Goodman as the man they were told via radio and TV ads to send a couple bucks to if they wanted to purchase the Dodgers' latest souvenir special. But Goodman was much more than a guy receiving checks and money orders. Any time you leave the ballpark with a T-shirt, a bobblehead, or some other souvenir of various niftiness, you can thank Goodman.

In the 1930s, when pretty much the only thing you could buy at a ballpark was food, Goodman essentially invented the ballpark souvenir industry while working concessions for the minor league Newark Bears. He came to the West Coast in 1938 as concessions manager for the Hollywood Stars, but soon made Los Angeles the center of the baseball novelty universe, long before the majors had ventured that far. Goodman supervised concessions for major and minor league teams across the country, so it was natural that when the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles, Goodman would come to work for them.

In 1962, Goodmanâwho also parlayed his experience into pioneering the Dodgers' annual Hollywood Stars Gameâand team public relations head Red Patterson suggested to Walter O'Malley that they give away Dodger caps to attendees at a game as a means to boost interest. The giveaway was a wild success, and led to the ubiquitous tradition of giveaways to lure fans to the ballpark. The success of this gimmick would seem to go without saying, but it didn't go without Goodman.