1491 (13 page)

After surprising the parish priest by their interest in his records, the two young men hauled into the church their principal research tool: a Contura portable copier, an ancestor to the Xerox photocopier that required freshly stirred chemicals for each use. The machine strained the technological infrastructure of Altar, which had electricity for only six hours a day. Under flickering light, the two men pored through centuries-old ledgers, the pages beautifully preserved by the dry desert air. Dobyns was struck by the disparity between the large number of burials recorded at the parish and the far smaller number of baptisms. Almost all the deaths were from diseases brought by Europeans. The Spaniards arrived and then Indians died—in huge numbers, at incredible rates. It hit him, Dobyns told me, “like a club right between the eyes.”

At first he did nothing about his observation. Historical demography was not supposed to be his field. Six years later, in 1959, he surveyed more archives in Hermosilla and found the same disparity. By this point he had almost finished his doctorate at Cornell and had been selected for Holmberg’s project. The choice was almost haphazard: Dobyns had never been to Peru.

Peru, Dobyns learned, was one of the world’s cultural wellsprings, a place as important to the human saga as the Fertile Crescent. Yet the area’s significance had been scarcely appreciated outside the Andes, partly because the Spaniards so thoroughly ravaged Inka culture, and partly because the Inka themselves, wanting to puff up their own importance, had actively concealed the glories of the cultures before them. Incredibly, the first full history of the fall of the Inka empire did not appear until more than three hundred years after the events it chronicled: William H. Prescott’s

History of the Conquest of Peru,

published in 1847. Prescott’s thunderous cadences remain a pleasure to read, despite the author’s firmly stated belief, typical for his time, in the moral inferiority of the natives. But the book had no successor. More than a century later, when Dobyns went to Lima, Prescott’s was still the only complete account. (A fine history, John Hemming’s

Conquest of the Incas,

appeared in 1970. But it, too, has had no successor, despite a wealth of new information.) “The Inka were largely ignored because the entire continent of South America was largely ignored,” Patricia Lyon, an anthropologist at the Institute for Andean Studies, in Berkeley, California, explained to me. Until the end of colonialism, she suggested, researchers tended to work in their own countries’ possessions. “The British were in Africa, along with the Germans and French. The Dutch were in Asia, and nobody was in South America,” because most of its nations were independent. The few researchers who did examine Andean societies were often sidetracked into ideological warfare. The Inka practiced a form of central planning, which led scholars into a sterile Cold War squabble about whether they were actually socialists

avant la lettre

in a communal Utopia or a dire precursor to Stalinist Russia.

Given the lack of previous investigation, it may have been inevitable that when Dobyns traced births and deaths in Lima he would be staking out new ground. He collected every book on Peruvian demography he could find. And he dipped into his own money to pay Cornell project workers to explore the cathedral archives and the national archives of Peru and the municipal archives of Lima. Slowly tallying mortality and natality figures, Dobyns continued to be impressed by what he found. Like any scholar, he eventually wrote an article about what he had learned. But by the time his article came out, in 1963, he had realized that his findings applied far beyond Peru.

The Inka and the Wampanoag were as different as Turks and Swedes. But Dobyns discovered, in effect, that their separate battles with Spain and England followed a similar biocultural template, one that explained the otherwise perplexing fact that

every

Indian culture, large or small, eventually succumbed to Europe. (Shouldn’t there have been

some

exceptions?) And then, reasoning backward in time from this master narrative, he proposed a new way to think about Native American societies, one that transformed not only our understanding of life before Columbus arrived, but our picture of the continents themselves.

TAWANTINSUYU

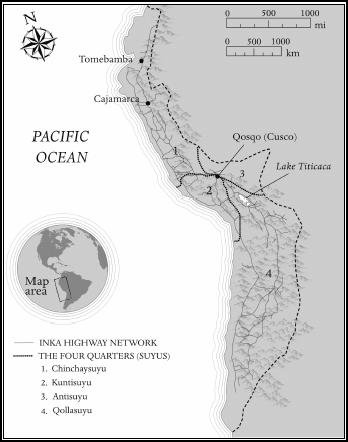

In 1491 the Inka ruled the greatest empire on earth. Bigger than Ming Dynasty China, bigger than Ivan the Great’s expanding Russia, bigger than Songhay in the Sahel or powerful Great Zimbabwe in the West Africa tablelands, bigger than the cresting Ottoman Empire, bigger than the Triple Alliance (as the Aztec empire is more precisely known), bigger by far than any European state, the Inka dominion extended over a staggering thirty-two degrees of latitude—as if a single power held sway from St. Petersburg to Cairo. The empire encompassed every imaginable type of terrain, from the rainforest of upper Amazonia to the deserts of the Peruvian coast and the twenty-thousand-foot peaks of the Andes between. “If imperial potential is judged in terms of environmental adaptability,” wrote the Oxford historian Felipe Fernández-Armesto, “the Inka were the most impressive empire builders of their day.”

The Inka goal was to knit the scores of different groups in western South America—some as rich as the Inka themselves, some poor and disorganized, all speaking different languages—into a single bureaucratic framework under the direct rule of the emperor. The unity was not merely political: the Inka wanted to meld together the area’s religion, economics, and arts. Their methods were audacious, brutal, and efficient: they removed entire populations from their homelands; shuttled them around the biggest road system on the planet, a mesh of stone-paved thoroughfares totaling as much as 25,000 miles; and forced them to work with other groups, using only Runa Sumi, the Inka language, on massive, faraway state farms and construction projects.

*7

To monitor this cyclopean enterprise, the Inka developed a form of writing unlike any other, sequences of knots on strings that formed a binary code reminiscent of today’s computer languages (see Appendix B, “Talking Knots”). So successful were the Inka at remolding their domain, according to the late John H. Rowe, an eminent archaeologist at the University of California at Berkeley, that Andean history “begins, not with the Wars of [South American] Independence or with the Spanish Conquest, but with the organizing genius of [empire founder] Pachakuti in the fifteenth century.”

TAWANTINSUYU

The Land of the Four Quarters, 1527

A.D.

Highland Peru is as extraordinary as the Inka themselves. It is the only place on earth, the Cornell anthropologist John Murra wrote, “where millions [of people] insist, against all apparent logic, on living at 10,000 or even 14,000 feet above sea level. Nowhere else have people lived for so many thousands of years in such visibly vulnerable circumstances.” And nowhere else have people living at such heights—in places where most crops won’t grow, earthquakes and landslides are frequent, and extremes of weather are the norm—repeatedly created technically advanced, long-lasting civilizations. The Inka homeland, uniquely high, was also uniquely steep, with slopes of more than sixty-five degrees from the horizontal. (The steepest street in San Francisco, famed for its nearly undrivable hills, is thirty-one-and-a-half degrees.) And it was uniquely narrow; the distance from the Pacific shore to the mountaintops is in most places less than seventy-five miles and in many less than fifty. Ecologists postulate that the first large-scale human societies tended to arise where, as Jared Diamond of the University of California at Los Angeles put it, geography provided “a wide range of altitudes and topographies within a short distance.” One such place is the Fertile Crescent, where the mountains of western Iran and the Dead Sea, the lowest place on earth, bracket the Tigris and Euphrates river systems. Another is Peru. In the short traverse from mountain to ocean, travelers pass through twenty of the world’s thirty-four principal types of environment.

Highland Peru, captured in this image of the Inka ruin Wiñay Wayna by the indigenous Andean photographer Martín Chambi (1891–1973), is the only place on earth where people living at such inhospitable altitudes repeatedly created materially sophisticated societies.

To survive in this steep, narrow hodgepodge of ecosystems, Andean communities usually sent out representatives and colonies to live up- or downslope in places with resources unavailable at home. Fish and shellfish from the ocean; beans, squash, and cotton from coastal river valleys; maize, potatoes, and the Andean grain quinoa from the foothills; llamas and alpacas for wool and meat in the heights—each area had something to contribute. Villagers in the satellite settlements exchanged products with the center, sending beans uphill and obtaining llama jerky in return, all the while retaining their citizenship in a homeland they rarely saw. Combining the fruits of many ecosystems, Andean cultures both enjoyed a better life than they could have wrested from any single place and spread out the risk from the area’s frequent natural catastrophes. Murra invented a name for this mode of existence: “vertical archipelagoes.”

Verticality helped Andean cultures survive but also pushed them to stay small. Because the mountains impeded north-south communication, it was much easier to coordinate the flow of goods and services east to west. As a result the region for most of its history was a jumble of small- and medium-scale cultures, isolated from all but their neighbors. Three times, though, cultures rose to dominate the Andes, uniting previously separate groups under a common banner. The first period of hegemony was that of Chavín, which from about 700

B.C.

to the dawn of the Christian era controlled the central coast of Peru and the adjacent mountains. The next, beginning after Chavín’s decline, was the time of two great powers: the technologically expert empire of Wari, which held sway over the coastline previously under Chavín; and Tiwanaku, centered on Lake Titicaca, the great alpine lake on the Peru-Bolivia border. (I briefly discussed Wari and Tiwanaku earlier, and will return to them—and to the rest of the immense pre-Inka tradition—later.) After Wari and Tiwanaku collapsed, at the end of the first millennium, the Andes split into sociopolitical fragments and with one major exception remained that way for more than three centuries. Then came the Inka.

The Inka empire, the greatest state ever seen in the Andes, was also the shortest lived. It began in the fifteenth century and lasted barely a hundred years before being smashed by Spain.

As conquerors, the Inka were unlikely. Even in 1350 they were still an unimportant part of the political scene in the central Andes, and newcomers at that. In one of the oral tales recorded by the Spanish Jesuit Bernabé Cobo, the Inka originated with a family of four brothers and four sisters who left Lake Titicaca for reasons unknown and wandered until they came upon what would become the future Inka capital, Qosqo (Cusco, in Spanish). Cobo, who sighed over the “extreme ignorance and barbarity” of the Indians, dismissed such stories as “ludicrous.” Nonetheless, archaeological investigation has generally borne them out: the Inka seem indeed to have migrated to Qosqo from somewhere else, perhaps Lake Titicaca, around 1200

A.D.

The colonial account of Inka history closest to indigenous sources is by Juan de Betanzos, a Spanish commoner who rose to marry an Inka princess and become the most prominent translator for the colonial government. Based on interviews with his in-laws, Betanzos estimated that when the Inka showed up in the Qosqo region “more than two hundred” small groups were already there. Qosqo itself, where they settled, was a hamlet “of about thirty small, humble straw houses.”