1491 (8 page)

Skipping over the complex course of Tisquantum’s life is understandable in a textbook with limited space. But the omission is symptomatic of the complete failure to consider Indian motives, or even that Indians might

have

motives. The alliance Massasoit negotiated with Plymouth was successful from the Wampanoag perspective, for it helped to hold off the Narragansett. But it was a disaster from the point of view of New England Indian society as a whole, for the alliance ensured the survival of Plymouth colony, which spearheaded the great wave of British immigration to New England. All of this was absent not only from my high school textbooks, but from the academic accounts they were based on.

This variant of Holmberg’s Mistake dates back to the Pilgrims themselves, who ascribed the lack of effective native resistance to the will of God. “Divine providence,” the colonist Daniel Gookin wrote, favored “the quiet and peaceable settlement of the English.” Later writers tended to attribute European success not to European deities but to European technology. In a contest where only one side had rifles and cannons, historians said, the other side’s motives were irrelevant. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Indians of the Northeast were thought of as rapidly fading background details in the saga of the rise of the United States—“marginal people who were losers in the end,” as James Axtell of the College of William and Mary dryly put it in an interview. Vietnam War–era denunciations of the Pilgrims as imperialist or racist simply replicated the error in a new form. Whether the cause was the Pilgrim God, Pilgrim guns, or Pilgrim greed, native losses were foreordained; Indians could not have stopped colonization, in this view, and they hardly tried.

Beginning in the 1970s, Axtell, Neal Salisbury, Francis Jennings, and other historians grew dissatisfied with this view. “Indians were seen as trivial, ineffectual patsies,” Salisbury, a historian at Smith College, told me. “But that assumption—a whole continent of patsies—simply didn’t make sense.” These researchers tried to peer through the colonial records to the Indian lives beneath. Their work fed a tsunami of inquiry into the interactions between natives and newcomers in the era when they faced each other as relative equals. “No other field in American history has grown as fast,” marveled Joyce Chaplin, a Harvard historian, in 2003.

The fall of Indian societies had everything to do with the natives themselves, researchers argue, rather than being religiously or technologically determined. (Here the claim is not that indigenous cultures should be blamed for their own demise but that they helped to determine their own fates.) “When you look at the historical record, it’s clear that Indians were trying to control their own destinies,” Salisbury said. “And often enough they succeeded”—only to learn, as all peoples do, that the consequences were not what they expected.

This chapter and the next will explore how two different Indian societies, the Wampanoag and the Inka, reacted to the incursions from across the sea. It may seem odd that a book about Indian life

before

contact should devote space to the period

after

contact, but there are reasons for it. First, colonial descriptions of Native Americans are among the few glimpses we have of Indians whose lives were not shaped by the presence of Europe. The accounts of the initial encounters between Indians and Europeans are windows into the past, even if the glass is smeared and distorted by the chroniclers’ prejudices and misapprehensions.

Second, although the stories of early contact—the Wampanoag with the British, the Inka with the Spanish—are as dissimilar as their protagonists, many archaeologists, anthropologists, and historians have recently come to believe that they have deep commonalities. And the tales of other Indians’ encounters with the strangers were alike in the same way. From these shared features, researchers have constructed what might be thought of as a master narrative of the meeting of Europe and America. Although it remains surprisingly little known outside specialist circles, this master narrative illuminates the origins of every nation in the Americas today. More than that, the effort to understand events after Columbus shed unexpected light on critical aspects of life

before

Columbus. Indeed, the master narrative led to such surprising conclusions about Native American societies before the arrival of Europeans that it stirred up an intellectual firestorm.

COMING OF AGE IN THE DAWNLAND

Consider Tisquantum, the “friendly Indian” of the textbook. More than likely Tisquantum was not the name he was given at birth. In that part of the Northeast,

tisquantum

referred to rage, especially the rage of

manitou,

the world-suffusing spiritual power at the heart of coastal Indians’ religious beliefs. When Tisquantum approached the Pilgrims and identified himself by that sobriquet, it was as if he had stuck out his hand and said, Hello, I’m the Wrath of God. No one would lightly adopt such a name in contemporary Western society. Neither would anyone in seventeenth-century indigenous society. Tisquantum was trying to project something.

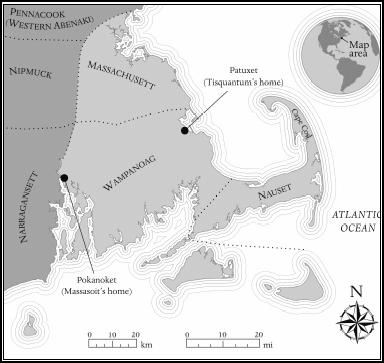

Tisquantum was not an Indian. True, he belonged to that category of people whose ancestors had inhabited the Western Hemisphere for thousands of years. And it is true that I refer to him as an Indian, because the label is useful shorthand; so would his descendants, and for much the same reason. But “Indian” was not a category that Tisquantum himself would have recognized, any more than the inhabitants of the same area today would call themselves “Western Hemisphereans.” Still less would Tisquantum have claimed to belong to “Norumbega,” the label by which most Europeans then referred to New England. (“New England” was coined only in 1616.) As Tisquantum’s later history made clear, he regarded himself first and foremost as a citizen of Patuxet, a shoreline settlement halfway between what is now Boston and the beginning of Cape Cod.

Patuxet was one of the dozen or so settlements in what is now eastern Massachusetts and Rhode Island that comprised the Wampanoag confederation. In turn, the Wampanoag were part of a tripartite alliance with two other confederations: the Nauset, which comprised some thirty groups on Cape Cod; and the Massachusett, several dozen villages clustered around Massachusetts Bay. All of these people spoke variants of Massachusett, a member of the Algonquian language family, the biggest in eastern North America at the time. (Massachusett thus was the name both of a language and of one of the groups that spoke it.) In Massachusett, the name for the New England shore was the Dawnland, the place where the sun rose. The inhabitants of the Dawnland were the People of the First Light.

MASSACHUSETT ALLIANCE, 1600 A.D.

Ten thousand years ago, when Indians in Mesoamerica and Peru were inventing agriculture and coalescing into villages, New England was barely inhabited, for the excellent reason that it had been covered until relatively recently by an ice sheet a mile thick. People slowly moved in, though the area long remained cold and uninviting, especially along the coastline. Because rising sea levels continually flooded the shore, marshy Cape Cod did not fully lock into its contemporary configuration until about 1000

B.C.

By that time the Dawnland had evolved into something more attractive: an ecological crazy quilt of wet maple forests, shellfish-studded tidal estuaries, thick highland woods, mossy bogs full of cranberries and orchids, fractally complex snarls of sandbars and beachfront, and fire-swept stands of pitch pine—“tremendous variety even within the compass of a few miles,” as the ecological historian William Cronon put it.

In the absence of written records, researchers have developed techniques for teasing out evidence of the past. Among them is “glottochronology,” the attempt to estimate how long ago two languages separated from a common ancestor by evaluating their degree of divergence on a list of key words. In the 1970s and 1980s linguists applied glottochronological techniques to the Algonquian dictionaries compiled by early colonists. However tentatively, the results indicated that the various Algonquian languages in New England all date back to a common ancestor that appeared in the Northeast a few centuries before Christ.

The ancestral language may derive from what is known as the Hopewell culture. Around two thousand years ago, Hopewell jumped into prominence from its bases in the Midwest, establishing a trade network that covered most of North America. The Hopewell culture introduced monumental earthworks and, possibly, agriculture to the rest of the cold North. Hopewell villages, unlike their more egalitarian neighbors, were stratified, with powerful, priestly rulers commanding a mass of commoners. Archaeologists have found no evidence of large-scale warfare at this time, and thus suggest that Hopewell probably did not achieve its dominance by conquest. Instead, one can speculate, the vehicle for transformation may have been Hopewell religion, with its intoxicatingly elaborate funeral rites. If so, the adoption of Algonquian in the Northeast would mark an era of spiritual ferment and heady conversion, much like the time when Islam rose and spread Arabic throughout the Middle East.

Hopewell itself declined around 400

A.D.

But its trade network remained intact. Shell beads from Florida, obsidian from the Rocky Mountains, and mica from Tennessee found their way to the Northeast. Borrowing technology and ideas from the Midwest, the nomadic peoples of New England transformed their societies. By the end of the first millennium

A.D.,

agriculture was spreading rapidly and the region was becoming an unusual patchwork of communities, each with its preferred terrain, way of subsistence, and cultural style.

Scattered about the many lakes, ponds, and swamps of the cold uplands were small, mobile groups of hunters and gatherers—“collectors,” as researchers sometimes call them. Most had recently adopted agriculture or were soon to do so, but it was still a secondary source of food, a supplement to the wild products of the land. New England’s major river valleys, by contrast, held large, permanent villages, many nestled in constellations of suburban hamlets and hunting camps. Because extensive fields of maize, beans, and squash surrounded every home, these settlements sprawled along the Connecticut, Charles, and other river valleys for miles, one town bumping up against the other. Along the coast, where Tisquantum and Massasoit lived, villages often were smaller and looser, though no less permanent.

Unlike the upland hunters, the Indians on the rivers and coastline did not roam the land; instead, most seem to have moved between a summer place and a winter place, like affluent snowbirds alternating between Manhattan and Miami. The distances were smaller, of course; shoreline families would move a fifteen-minute walk inland, to avoid direct exposure to winter storms and tides. Each village had its own distinct mix of farming and foraging—this one here, adjacent to a rich oyster bed, might plant maize purely for variety, whereas that one there, just a few miles away, might subsist almost entirely on its harvest, filling great underground storage pits each fall. Although these settlements were permanent, winter and summer alike, they often were not tightly knit entities, with houses and fields in carefully demarcated clusters. Instead people spread themselves through estuaries, sometimes grouping into neighborhoods, sometimes with each family on its own, its maize ground proudly separate. Each community was constantly “joining and splitting like quicksilver in a fluid pattern within its bounds,” wrote Kathleen J. Bragdon, an anthropologist at the College of William and Mary—a type of settlement, she remarked, with “no name in the archaeological or anthropological literature.”

In the Wampanoag confederation, one of these quicksilver communities was Patuxet, where Tisquantum was born at the end of the sixteenth century.

Tucked into the great sweep of Cape Cod Bay, Patuxet sat on a low rise above a small harbor, jigsawed by sandbars and shallow enough that children could walk from the beach hundreds of yards into the water before the waves went above their heads. To the west, maize hills marched across the sandy hillocks in parallel rows. Beyond the fields, a mile or more away from the sea, rose a forest of oak, chestnut, and hickory, open and park-like, the underbrush kept down by expert annual burning. “Pleasant of air and prospect,” as one English visitor described the area, Patuxet had “much plenty both of fish and fowl every day in the year.” Runs of spawning Atlantic salmon, short-nose sturgeon, striped bass, and American shad annually filled the harbor. But the most important fish harvest came in late spring, when the herring-like alewives swarmed the fast, shallow stream that cut through the village. So numerous were the fish, and so driven, that when mischievous boys walled off the stream with stones the alewives would leap the barrier—silver bodies gleaming in the sun—and proceed upstream.