1491 (25 page)

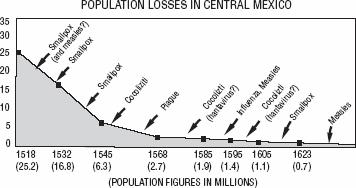

Berkeley researchers Cook and Borah spent decades reconstructing the population of the former Triple Alliance realm in the wake of the Spanish conquest. By combining colonial-era data from many sources, the two men estimated that the number of people in the region fell from 25.2 million in 1518, just before Cortés arrived, to about 700,000 in 1623—a 97 percent drop in little more than a century. (Each marked date is one for which they presented a population estimate.) Using parish records, Mexican demographer Elsa Malvido calculated the sequence of epidemics in the region, portions of which are shown here. Dates are approximate, because epidemics would last several years. The identification of some diseases is uncertain as well; for example, sixteenth-century Spaniards lumped together what today are seen as distinct maladies under the rubric “plague.” In addition, native populations were repeatedly struck by “cocoliztli,” a disease the Spanish did not know but that scientists have suggested might be a rat-borne hantavirus—spread, in part, by the postconquest collapse of Indian sanitation measures. Both reconstructions are tentative, but the combined picture of catastrophic depopulation has convinced most researchers in the field.

Katz overstates his case. True, the conquistadors did not want the Indians to die off en masse. But that desire did not stem from humanitarian motives. Instead, the Spanish wanted native peoples to use as a source of forced labor. In fact, the Indian deaths were such a severe financial blow to the colonies that they led, according to Borah, to an “economic depression” that lasted “more than a century.” To resupply themselves with labor, the Spaniards began importing slaves from Africa.

Later on, some of the newcomers indeed campaigned in favor of eradicating natives. The poet-physician Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., for instance, regarded the Indian as but “a sketch in red crayon of a rudimental manhood.” To the “problem of his relation to the white race,” Holmes said, there was one solution: “extermination.” Following such impulses, a few Spanish—and a few French, Portuguese, and British—deliberately spread disease. Many more treated Indians cruelly, murderously so, killing countless thousands. But the pain and death caused from the deliberate epidemics, lethal cruelty, and egregious racism pale in comparison to those caused by the great waves of disease, a means of subjugation that the Europeans could not control and in many cases did not know they had. How can they be morally culpable for it?

Not so fast, say the activists. Europeans may not have known about microbes, but they thoroughly understood infectious disease. Almost 150 years before Columbus set sail, a Tartar army besieged the Genoese city of Kaffa. Then the Black Death visited. To the defenders’ joy, their attackers began dying off. But triumph turned to terror when the Tartar khan catapulted the dead bodies of his men over the city walls, deliberately creating an epidemic inside. The Genoese fled Kaffa, leaving it open to the Tartars. But they did not run away fast enough; their ships spread the disease to every port they visited.

Coming from places that had suffered many such experiences, Europeans fully grasped the potential consequences of smallpox. “And what was their collective response to this understanding?” asked Ward Churchill, a professor of ethnic studies at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

Did they recoil in horror and say, “Wait a minute, we’ve got to halt the process, or at least slow it down until we can get a handle on how to prevent these effects”? Nope. Their response pretty much across-the-board was to accelerate their rate of arrival, and to spread out as much as was humanly possible.

But this, too, overstates the case. Neither European nor Indian had a secular understanding of disease. “Sickness was the physical manifestation of the will of God,” Robert Crease, a philosopher of science at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, told me. “You could pass it on to someone, but doing that was like passing on evil, or bad luck, or a bad spirit—the transmission also reflected God’s will.” The conquistadors knew the potential impact of disease, but its

actual

impact, which they could not control, was in the hands of God.

The Mexica agreed. In all the indigenous accounts of the conquest and its aftermath, the anthropologist J. Jorge Klor de Alva observed, the Mexica lament their losses, but, “the Spaniards are rarely judged in moral terms, and Cortés is only sporadically considered a villain. It seems to be commonly understood”—at least by this bleakly philosophical, imperially minded group—“that the Spaniards did what any other group would have done or would have been expected to do if the opportunity had existed.”

Famously, the conquistador Bernal Díaz de Castillo ticked off the reasons he and others joined Cortés: “to serve God and His Majesty [the king of Spain], to give light to those who were in darkness, and to grow rich, as all men desire to do.” In Díaz’s list, spiritual and material motivations were equally important. Cortés was constantly preoccupied by the search for gold, but he also had to be restrained by the priests accompanying him from promulgating the Gospel in circumstances sure to anger native leaders. After the destruction of Tenochtitlan, the Spanish court and intellectual elite were convulsed with argument for a century about whether the conversions were worth the suffering inflicted. Many believed that even if Indians died soon after conversion, good could still occur. “Christianity is not about getting healthy, it’s about getting saved,” Crease said, summarizing. Today few Christians would endorse this argument, but that doesn’t make it any easier to assign the correct degree of blame to their ancestors.

In an editorial about Black’s analysis of Indian HLA profiles, Jean-Claude Salomon, a medical researcher at France’s Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, asked if the likely inevitability of native deaths could “reduce the historical guilt of Europeans.” In a sense it does, Salomon wrote. But it did not let the invaders off the hook—they caused huge numbers of deaths, and knew that they had done it. “Those who carried the microbes across the Atlantic were responsible, but not guilty,” Salomon concluded. Guilt is not readily passed down the generations, but responsibility can be. A first step toward satisfying that responsibility for Europeans and their descendants in North and South America would be to treat indigenous people today with respect—something that, alas, cannot yet be taken for granted. Recognizing and obeying past treaties wouldn’t be a bad idea, either.

ISN’T THIS ALL JUST REVISIONISM?

Yes, of course—except that it’s more like

re-

revisionism. The first European adventurers in the Western Hemisphere did not make careful population counts, but they repeatedly described indigenous America as a crowded, jostling place—“a beehive of people,” as Las Casas put it in 1542. To Las Casas, the Americas seemed so thick with people “that it looked as if God has placed all of or the greater part of the entire human race in these countries.”

So far as is known, Las Casas never tried to enumerate the original native population. But he did try to calculate how many died from Spanish disease and brutality. In Las Casas’s “sure, truthful estimate,” his countrymen in the first five decades after Columbus wiped out “more than twelve million souls, men and women and children; and in truth I believe, without trying to deceive myself, that it was more than fifteen million.” Twenty years later, he raised his estimate of Indian deaths—and hence of the initial population—to forty million.

Las Casas’s successors usually shared his ideas—the eighteenth-century Jesuit Francisco Javier Clavijero, for example, asserted that the pre-Columbian population of Mexico alone was thirty million. But gradually a note of doubt crept in. To most historians, the colonial accounts came to seem exaggerated, though exactly why was not often explained. (“Sixteenth-century Europeans,” Cook and Borah dryly remarked, “did indeed know how to count.”) Especially in North America, historians’ guesses at native numbers kept slipping down. By the 1920s they had dwindled to forty or fifty million in the entire hemisphere—about the number that Las Casas believed had died in Mesoamerica alone. Twenty years after that, the estimates had declined by another factor of five.

Today the picture has reversed. The High Counters seem to be winning the argument, at least for now. No definitive data exist, but the majority of the extant evidentiary scraps indicate it. “Most of the arrows point in that direction,” Denevan said to me. Zambardino, the computer scientist who decried the margin of error in these estimates, noted that even an extremely conservative extrapolation of known figures would still project a precontact population in central Mexico alone of five to ten million, “a very high population, not only in terms of the sixteenth century, but indeed on any terms.” Even Henige, of

Numbers from Nowhere,

is no Low Counter. In

Numbers from Nowhere

, he argues that “perhaps 40 million throughout the Western Hemisphere” is a “not unreasonable” figure—putting him at the low end of the High Counters, but a High Counter nonetheless. Indeed, it is the same figure provided by Las Casas, patron saint of High Counters, foremost among the old Spanish sources whose estimates Henige spends many pages discounting.

To Fenn, the smallpox historian, the squabble over the number of deaths and the degree of blame obscures something more important. In the long run, Fenn says, the consequential finding of the new scholarship is not that many people died but that many people

lived.

The Americas were filled with an enthusiastically diverse assortment of peoples who had knocked about the continents for millennia. “We are talking about enormous numbers of people,” she told me. “You have to wonder, Who were all these people? And what were they doing?”

PART TWO

Very Old Bones

Pleistocene Wars

POSSIBLY A VERY ODD HAPLOGROUP

The last time I spoke with Sérgio D. J. Pena, he was hunting for ancient Indians in modern blood. The blood was sealed into thin, rodlike vials in Pena’s laboratory at the Federal University of Minas Gerais, in Belo Horizonte, Brazil’s third-largest city. To anyone who has seen a molecular biology lab on the television news, the racks of refrigerating tanks, whirling DNA extractors, and gene-sequencing machines in Pena’s lab would look familiar. But what Pena was doing with them would not. One way to describe Pena’s goal would be to say that he was trying to bring back a people who vanished thousands of years ago. Another would be to say that he was wrestling with a scientific puzzle that had resisted resolution since 1840.