1812: The Navy's War (16 page)

As soon as he got the chance, Hull sent a letter to Hamilton, telling him that if new orders did not arrive, he planned to sail eastward and join Rodgers’s squadron, although it’s hard to believe he didn’t prefer being on his own. He immediately began replenishing the

Constitution

, particularly the water he had pumped overboard. When he left Chesapeake Bay two weeks before, he expected to be sailing to New York and had taken on board only eight weeks’ worth of supplies. He had already consumed over a third of them. While he worked, the dreaded new orders from Hamilton were on the way, directing him to turn over command of the

Constitution

to his senior, Captain William Bainbridge, and return to Washington, where he was to take command of the smaller frigate

Constellation

. A bit later, after Hamilton found out about Hull’s inspiring escape from Broke, he changed these instructions and directed Hull to “remain at Boston until further orders”—just what Hull did not want to hear. Hamilton and the president still had no confidence in the fleet and no plan for it, other than confining it to port.

Constitution

, particularly the water he had pumped overboard. When he left Chesapeake Bay two weeks before, he expected to be sailing to New York and had taken on board only eight weeks’ worth of supplies. He had already consumed over a third of them. While he worked, the dreaded new orders from Hamilton were on the way, directing him to turn over command of the

Constitution

to his senior, Captain William Bainbridge, and return to Washington, where he was to take command of the smaller frigate

Constellation

. A bit later, after Hamilton found out about Hull’s inspiring escape from Broke, he changed these instructions and directed Hull to “remain at Boston until further orders”—just what Hull did not want to hear. Hamilton and the president still had no confidence in the fleet and no plan for it, other than confining it to port.

While the new orders were still in transit, Hull completed work on the

Constitution

, and when the wind had hauled far to the westward during the wee hours of Sunday morning, August 2, Hull unmoored and fetched out of the harbor. At seven o’clock he was hove to beyond Boston Light, waiting for a boat he had dispatched to check the post office one last time. When the boat returned with no news from Hamilton, a relieved Hull sped out to sea.

Constitution

, and when the wind had hauled far to the westward during the wee hours of Sunday morning, August 2, Hull unmoored and fetched out of the harbor. At seven o’clock he was hove to beyond Boston Light, waiting for a boat he had dispatched to check the post office one last time. When the boat returned with no news from Hamilton, a relieved Hull sped out to sea.

At first, he sailed northeast along the Maine coast to the Bay of Fundy. Finding no enemy ships, he turned east and steered for Cape Sable Island at the southern tip of Nova Scotia, intending to patrol between there and Halifax. Four uneventful days later, Hull decided to stand toward Newfoundland. He was under full sail when he passed Sable Island, and he then hauled in to take up a station off the Gulf of St. Lawrence near Cape Race at the southeastern tip of Newfoundland, hoping to intercept ships bound for Quebec or Halifax.

On August 10 and 11, Hull captured two small, empty British vessels, and after taking their crews aboard the

Constitution

, he burned them. Four days later, as dawn approached on the fifteenth, lookouts saw five sail dead ahead, looking like a convoy. Hull put on a full press of sail in pursuit. By sunrise it was clear that one was a small warship (the 18-gun British sloop of war

Avenger

with a crew of 121). At six o’clock the

Avenger

discovered the

Constitution

and immediately cast off a prize she had in tow and burned her, before making all sail to windward and fleeing. Being more weatherly than the

Constitution

, that is, able to sail closer to the wind with little leeway, she made good her escape. While she did, Hull chased down another vessel in the vicinity, which turned out to be a British prize of the privateer

Dolphin

out of Salem, Massachusetts. The

Dolphin

was nowhere in sight; she had abandoned her prize and raced away when she saw the

Avenger

.

Constitution

, he burned them. Four days later, as dawn approached on the fifteenth, lookouts saw five sail dead ahead, looking like a convoy. Hull put on a full press of sail in pursuit. By sunrise it was clear that one was a small warship (the 18-gun British sloop of war

Avenger

with a crew of 121). At six o’clock the

Avenger

discovered the

Constitution

and immediately cast off a prize she had in tow and burned her, before making all sail to windward and fleeing. Being more weatherly than the

Constitution

, that is, able to sail closer to the wind with little leeway, she made good her escape. While she did, Hull chased down another vessel in the vicinity, which turned out to be a British prize of the privateer

Dolphin

out of Salem, Massachusetts. The

Dolphin

was nowhere in sight; she had abandoned her prize and raced away when she saw the

Avenger

.

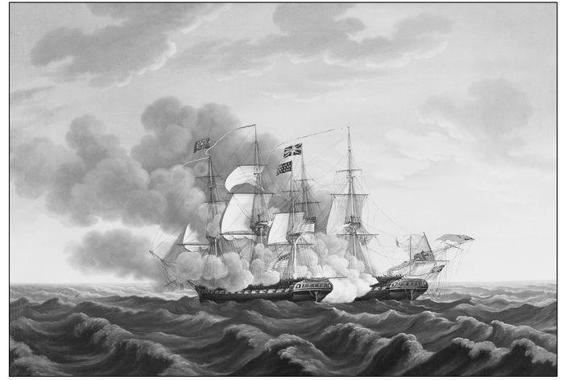

Figure 7.1: Michele Felice Cornè, Constitution

and

Guerriere

, 19 August 1812

(courtesy of U.S. Naval Academy Museum).

and

Guerriere

, 19 August 1812

(courtesy of U.S. Naval Academy Museum).

That same day Hull gave chase to another brig the

Constitution

’s lookouts had spotted, and when he caught up with her, he discovered she was an American prize of the

Avenger

, with a British prize master and a small British crew aboard. From the master Hull learned he had narrowly missed sailing into Broke’s squadron, which was at the western edge of the Grand Banks looking for Commodore Rodgers, trying to intercept him before he caught the Jamaica convoy. Hull decided to put some distance between himself and Broke and turned south toward Bermuda.

Constitution

’s lookouts had spotted, and when he caught up with her, he discovered she was an American prize of the

Avenger

, with a British prize master and a small British crew aboard. From the master Hull learned he had narrowly missed sailing into Broke’s squadron, which was at the western edge of the Grand Banks looking for Commodore Rodgers, trying to intercept him before he caught the Jamaica convoy. Hull decided to put some distance between himself and Broke and turned south toward Bermuda.

On the eighteenth at 9:30 at night, lookouts saw a brig close by, and Hull gave chase, catching up with her at 11. She turned out to be the 14-gun American privateer

Decatur

out of Newburyport, Massachusetts, with a crew of 108, under Captain William Nicholls. In trying to escape from the big unknown frigate, Nicholls had thrown overboard twelve precious guns. He had taken nine prizes during a short cruise, demonstrating that Madison’s privateers were already swarming around British shipping lanes. In these waters, the privateers were usually from Federalist Massachusetts. Even though most of the merchants in places like Newburyport and Salem opposed the war, they were not averse to making money from it.

Decatur

out of Newburyport, Massachusetts, with a crew of 108, under Captain William Nicholls. In trying to escape from the big unknown frigate, Nicholls had thrown overboard twelve precious guns. He had taken nine prizes during a short cruise, demonstrating that Madison’s privateers were already swarming around British shipping lanes. In these waters, the privateers were usually from Federalist Massachusetts. Even though most of the merchants in places like Newburyport and Salem opposed the war, they were not averse to making money from it.

When Nicholls came aboard the

Constitution

, he told Hull he had seen a large warship nearby standing southward. Hull was excited; he immediately turned south, hoping to fall in with her. At 2 P.M. the following day, August 19, Hull’s lookouts spied a sail in the distance to leeward. The

Constitution

was moving south southwest in latitude 41° 42’ and longitude 55° 48’. With an accommodating wind from the northwest, Hull put on all sail and sped toward the stranger. She did not appear to be running away. By three o’clock Hull could see she was a large ship on the starboard tack, close by the wind under easy sail. By 3:30 it was plain she was just what he had hoped, a British frigate. His heart must have been racing, for there is no doubt he recognized her as the

Guerriere

, one of the frigates that chased him during his race with Broke’s squadron.

Constitution

, he told Hull he had seen a large warship nearby standing southward. Hull was excited; he immediately turned south, hoping to fall in with her. At 2 P.M. the following day, August 19, Hull’s lookouts spied a sail in the distance to leeward. The

Constitution

was moving south southwest in latitude 41° 42’ and longitude 55° 48’. With an accommodating wind from the northwest, Hull put on all sail and sped toward the stranger. She did not appear to be running away. By three o’clock Hull could see she was a large ship on the starboard tack, close by the wind under easy sail. By 3:30 it was plain she was just what he had hoped, a British frigate. His heart must have been racing, for there is no doubt he recognized her as the

Guerriere

, one of the frigates that chased him during his race with Broke’s squadron.

Fifteen minutes later, the British ship backed her main topsail and lay by on the starboard tack, inviting a duel with the bigger

Constitution

. The

Guerriere

’s skipper, twenty-eight-year-old Captain James Dacres, had been detached from Broke’s squadron and was making his way to Halifax for a refit. He could not have been happier to see the

Constitution

. Even at his young age, he was an accomplished fighter with a distinguished record. He was from an old navy clan—his father and uncle were both admirals—and he proudly carried on the family’s tradition. Although his ship was smaller than the

Constitution

, she was one of the finest frigates in the British fleet. Dacres expected to make quick work of the American. He was so confident he magnanimously allowed ten impressed Americans aboard to go below when they insisted they would not fight against their countrymen. The British had grown accustomed to victory, even when the odds were against them. A difference in size between the two frigates, even a significant one, made no difference to the proud lions of the Royal Navy. Defeat at the hands of an American crew was inconceivable. The officers and men of the

Guerriere

, like all their countrymen, had nothing but contempt for the American navy.

Constitution

. The

Guerriere

’s skipper, twenty-eight-year-old Captain James Dacres, had been detached from Broke’s squadron and was making his way to Halifax for a refit. He could not have been happier to see the

Constitution

. Even at his young age, he was an accomplished fighter with a distinguished record. He was from an old navy clan—his father and uncle were both admirals—and he proudly carried on the family’s tradition. Although his ship was smaller than the

Constitution

, she was one of the finest frigates in the British fleet. Dacres expected to make quick work of the American. He was so confident he magnanimously allowed ten impressed Americans aboard to go below when they insisted they would not fight against their countrymen. The British had grown accustomed to victory, even when the odds were against them. A difference in size between the two frigates, even a significant one, made no difference to the proud lions of the Royal Navy. Defeat at the hands of an American crew was inconceivable. The officers and men of the

Guerriere

, like all their countrymen, had nothing but contempt for the American navy.

The

Constitution

had a complement of 456 men and was rated at forty-four guns but mounted fifty-six, including thirty twenty-four-pound long guns on the main deck, twenty-four thirty-two-pound carronades on the spar deck, and two long eighteen-pounders at the bow. (Carronades were small, lightweight cannon with wide, short barrels that had a limited effective range of less than five hundred yards but fired large-caliber projectiles.) The

Guerriere

—undermanned as most British warships—had a crew of only 272, not counting the Americans aboard. She was rated at thirty-eight guns and carried forty-nine. On her main deck thirty eighteen-pound long guns were mounted, and on her spar deck she had sixteen thirty-two-pound carronades, two long twelves, and a twelve-pound howitzer. The

Constitution

’s broadside in weight of metal was a potent 762 pounds, while the

Guerriere

’s was a bit more than 550. The quality of the officers and crews of both ships, which in the end would make the difference, could not be so easily measured.

Constitution

had a complement of 456 men and was rated at forty-four guns but mounted fifty-six, including thirty twenty-four-pound long guns on the main deck, twenty-four thirty-two-pound carronades on the spar deck, and two long eighteen-pounders at the bow. (Carronades were small, lightweight cannon with wide, short barrels that had a limited effective range of less than five hundred yards but fired large-caliber projectiles.) The

Guerriere

—undermanned as most British warships—had a crew of only 272, not counting the Americans aboard. She was rated at thirty-eight guns and carried forty-nine. On her main deck thirty eighteen-pound long guns were mounted, and on her spar deck she had sixteen thirty-two-pound carronades, two long twelves, and a twelve-pound howitzer. The

Constitution

’s broadside in weight of metal was a potent 762 pounds, while the

Guerriere

’s was a bit more than 550. The quality of the officers and crews of both ships, which in the end would make the difference, could not be so easily measured.

Hull cleared for action around three o’clock, ordering light sails taken in and royal yards struck down, two reefs taken in the topsails, and the foresail and mainsail hauled up. While a marine drummer beat the call to quarters, and all hands raced to their battle stations, Hull steered straight for the enemy, some three miles away now. As the big ship plowed ahead, the crew gave three cheers, even though everyone knew a gruesome, bloody brawl was only minutes away. Hull later claimed there were no anxious faces. He said the men made it clear to him they wanted to lay the

Constitution

close alongside the enemy and blaze away. That may or may not have been the case, but there was no doubt Hull himself was fixed on a toe-to-toe slugfest, and by the look of things, so was the British captain.

Constitution

close alongside the enemy and blaze away. That may or may not have been the case, but there was no doubt Hull himself was fixed on a toe-to-toe slugfest, and by the look of things, so was the British captain.

“Hull was now all animation,” Moses Smith reported. “With great energy and calmness . . . he passed around among the officers and men, [saying] . . . ‘now do your duty. Your officers cannot have entire command over you now. Each man must do all in his power for his country.’”

As Hull bore up, Dacres hoisted an ensign at the mizzen gaff, another in the mizzen shrouds, and jacks at the foretopgallant and mizzen topgallant mastheads. At 5:05 the

Constitution

continued to run down on the enemy, and as she did, the

Guerriere

fired a broadside, but the balls fell short. A sea was running, and her gunners might not have adjusted sufficiently for the roll of the ship. Dacres then wore and gave the

Constitution

a broadside with his larboard guns. Only two balls struck, however, and they bounced harmlessly off the

Constitution

’s thick hide, earning her the immortal sobriquet “Old Ironsides.” Hull moved closer and hoisted American colors at the mizzen peak, the foretopgallant, and the mizzen topgallant mastheads, and he made one ready for hoisting at the main masthead. All the while, Dacres had been maneuvering to gain the weather gauge, but finding he could not, he bore up to bring the wind on his quarter and ran under topsails and jib, firing at the

Constitution

as he went.

Constitution

continued to run down on the enemy, and as she did, the

Guerriere

fired a broadside, but the balls fell short. A sea was running, and her gunners might not have adjusted sufficiently for the roll of the ship. Dacres then wore and gave the

Constitution

a broadside with his larboard guns. Only two balls struck, however, and they bounced harmlessly off the

Constitution

’s thick hide, earning her the immortal sobriquet “Old Ironsides.” Hull moved closer and hoisted American colors at the mizzen peak, the foretopgallant, and the mizzen topgallant mastheads, and he made one ready for hoisting at the main masthead. All the while, Dacres had been maneuvering to gain the weather gauge, but finding he could not, he bore up to bring the wind on his quarter and ran under topsails and jib, firing at the

Constitution

as he went.

Hull responded by setting his main topgallant and closing on the

Guerriere

’s larboard quarter. Once there, the

Constitution

passed to the

Guerriere

’s beam, the distance between them narrowing from two hundred yards to a half pistol shot (ten yards). It was six o’clock. Hull had fired only a few shots as he approached, but now he let loose a barrage of crushing broadsides, his double-shotted twenty-four-pounders spewing out deadly round and grapeshot. They were far more devastating than the

Guerriere

’s eighteens, and they staggered the smaller ship. Dacres fired back as fast as he could. But in fifteen minutes the

Guerriere

’s mizzenmast went by the board, and her main yard was in the slings, while her hull and sails had taken a tremendous beating.

Guerriere

’s larboard quarter. Once there, the

Constitution

passed to the

Guerriere

’s beam, the distance between them narrowing from two hundred yards to a half pistol shot (ten yards). It was six o’clock. Hull had fired only a few shots as he approached, but now he let loose a barrage of crushing broadsides, his double-shotted twenty-four-pounders spewing out deadly round and grapeshot. They were far more devastating than the

Guerriere

’s eighteens, and they staggered the smaller ship. Dacres fired back as fast as he could. But in fifteen minutes the

Guerriere

’s mizzenmast went by the board, and her main yard was in the slings, while her hull and sails had taken a tremendous beating.

Dacres was in trouble. His mizzenmast had fallen over the starboard quarter, but its still uncut standing rigging held it fast to the ship, making her impossible to maneuver, and she swung up into the wind. Meanwhile, Hull put the

Constitution

hard to port, crossed the enemy’s bows, and raked her. He then wore ship and came back across her bows again, delivering another crushing broadside with his portside guns. The two raking broadsides created havoc on the

Guerriere

’s forecastle, and ripped into her sails and fore rigging. At the same time, she had use of only a few of her bow guns. Meanwhile, Hull’s sharpshooters in the tops rained musket balls down on the

Guerriere

’s deck.

Constitution

hard to port, crossed the enemy’s bows, and raked her. He then wore ship and came back across her bows again, delivering another crushing broadside with his portside guns. The two raking broadsides created havoc on the

Guerriere

’s forecastle, and ripped into her sails and fore rigging. At the same time, she had use of only a few of her bow guns. Meanwhile, Hull’s sharpshooters in the tops rained musket balls down on the

Guerriere

’s deck.

Dacres tried putting his ship hard to port, but her helm would not answer, and her bowsprit and jib-boom swept over the

Constitution

’s quarterdeck, becoming entangled in the lee mizzen rigging, causing the

Guerriere

to fall astern of the

Constitution

. The ships were now tenuously hitched together. Lieutenant Charles Morris leaped up on the taffrail to see if Dacres was forming a boarding party. He was. Boarding was his only chance now. Although the American crew far outnumbered his own, he might get lucky. In any event, he was determined to fight it out hand-to-hand.

Constitution

’s quarterdeck, becoming entangled in the lee mizzen rigging, causing the

Guerriere

to fall astern of the

Constitution

. The ships were now tenuously hitched together. Lieutenant Charles Morris leaped up on the taffrail to see if Dacres was forming a boarding party. He was. Boarding was his only chance now. Although the American crew far outnumbered his own, he might get lucky. In any event, he was determined to fight it out hand-to-hand.

When Morris saw Dacres preparing to board, he shouted to Hull, and the captain ordered his own boarders to assemble. Trumpets were now sounding on both ships, calling the boarding parties. While waiting for his men to gather, Morris began wrapping the main brace over the

Guerriere

’s bowsprit to better fasten the ships together. Suddenly, a musket ball, fired by one of the

Guerriere

’s marines assembling to board, struck him in the body, and threw him back on deck, stunned. Lieutenant William Bush of the marines was standing nearby, and another ball hit him, killing him instantly. Sailing Master John Aylwin was grazed on the shoulder by another. Despite his injury, Morris somehow stood up and remained in the fight.

Guerriere

’s bowsprit to better fasten the ships together. Suddenly, a musket ball, fired by one of the

Guerriere

’s marines assembling to board, struck him in the body, and threw him back on deck, stunned. Lieutenant William Bush of the marines was standing nearby, and another ball hit him, killing him instantly. Sailing Master John Aylwin was grazed on the shoulder by another. Despite his injury, Morris somehow stood up and remained in the fight.

The ships now separated unexpectedly, making boarding impossible. Hull resumed pummeling the enemy from a short distance for several minutes, when the

Guerriere

’s foremast and mainmast suddenly went over the side, taking with them the jib boom and every spar except the bowsprit. She was now completely disabled, rolling helplessly in the trough of the sea, taking in water from open gun ports and shot holes in her hull.

Guerriere

’s foremast and mainmast suddenly went over the side, taking with them the jib boom and every spar except the bowsprit. She was now completely disabled, rolling helplessly in the trough of the sea, taking in water from open gun ports and shot holes in her hull.

Other books

Discovery by Lisa White

Future Shock by Elizabeth Briggs

Revenge by Mark A. Cooper

Z-Risen (Book 3): Poisoned Earth by Long, Timothy W.

Little Round Head by Michael Marano

Love Letters from Ladybug Farm by Donna Ball

A Woman in Berlin : Eight Weeks in the Conquered City: A Diary by Marta Hillers

Land of Enchantment by Janet Dailey

Follow A Wild Heart (romance,) by Hutchinson, Bobby

Which Way to the Wild West? by Steve Sheinkin