1912 (31 page)

Authors: Chris Turney

Ever ambitious, Filchner soon reported to the American Geographical Society that he was keen to give the south another go. âAbout May the

Deutschland

will reach Buenos Aires and then go into dry dock in order to carry out a trip to the Sandwich Islands southeast of South Georgia, during the current year. At the end of the year the second trip to the newly discovered land can be made again and the explorations in the Antarctic continue according to the original program.'

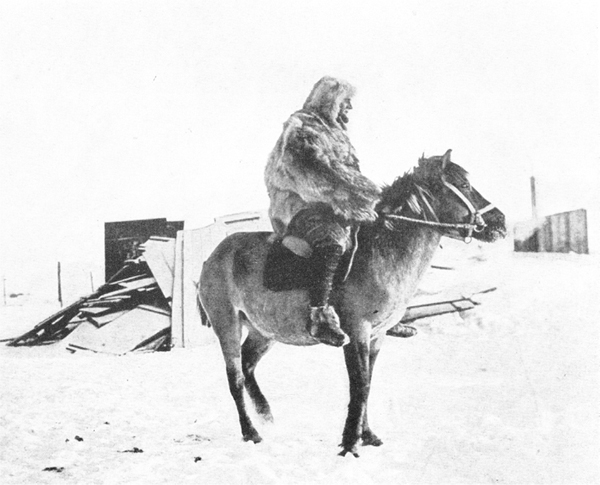

It was not to be. Those sent back to Germany early had returned with tales of poor leadership and low morale. The fallout reached Filchner's superiors, and he was ordered to return home and answer charges. His plans for further work in Antarctica were quietly shelved. The Siberian dogs and horses

were left behind in South Georgia and died from lack of food, victims of a thwarted expedition.

In Germany the recriminations came swiftly. Accusations raged in the press and a Court of Honour was established. All accusations were heard. Although the court was not legally binding, the disputes it addressed were intended to be settled privately, instead of in the media. The verdict was not what Filchner's opponents wanted: he was not castigated for his leadership, and several of the scientists continued to back him.

Filchner wrote, âThe verdict of the Court of Honour included, among other things, the clause that the scientists who were aboard

Deutschland

had refused to publish their expedition results in co-operation with me. This representation did not correspond to reality, since the expedition astronomer Prof. Dr Przybyllok had not been in agreement with this protest; for his part he rejected the unfair demand that he should publish his results along with the other scientists.'

The protagonists appear to have ignored the court's verdict and continued to make public accusations. Filchner later remarked, âWhen, after this failure, my enemies circulated the story, that I had achieved nothing scientifically on the polar voyage, this rhetoric did not especially disturb me, since it was familiar to me.'

Not everyone was convinced by the denouncements. The Kaiser invited the German expedition leader to his castle at Doon and gave him his backing. Penck wrote a public essay on the expedition in early 1914, defending Filchner and the mission's success. To him, it was clear where the blame lay: Vahsel and the naval leadership imposed on Filchner.

Still rumours abounded, with von Goeldel claiming that Filchner was not âa man of honour'. In the traditional Teutonic way, he was challenged to a duel and the comment was swiftly withdrawn.

After her return to Europe the

Deutschland

was sold to Austria, so that a restored König could lead another trip south and finish the job. Filchner was invited to take part, but felt âfor the time being I had had enough of “Antarctic Doings”. Moreover, many experiences had convinced me that truly great successes in the polar ice are granted only to members of those nations where polar research has tradition, namely the Scandinavians, the Russians, the British and the Canadians. I [have] decided to return to my original field of work: Central and East Asia.' First, Filchner got on with writing up the scientific output of the Antarctic expedition as best he could.

Filchner's efforts in the south became synonymous with failure in Germany, but were followed with interest overseas. Early in the expedition many commentators pondered what had happened to the

Deutschland

, with one writing, âA guess may be hazarded. Lieutenant Filchner is probably wintering somewhere under the lee of Coats Land. For aught we know to the contrary, there may be another range of mountains there pointing towards the South Pole; at any rate, it seems probable that Filchner will have better weather thanâ¦Scott, and that this may aid him in breaking a new trail to the South Pole.'

On the Germans' return, the international enthusiasm was undiminished. Learned societies and individuals were effusive about the expedition's achievements. The Germans had heroically fought their way to the southernmost end of a vast Atlantic-facing ocean. And after traversing the extent of the Weddell Sea, Filchner had reached a previously undiscovered shore that set a northern limit to the continent.

The discoveries seemed to show there was no strait beyond the Weddell Sea. Instead, the ocean was backed by an

enormous ice shelf that soon lost the regal name bequeathed to it and became known as the Filchner Ice Shelf. On the other side of Antarctica the Japanese and Norwegians appeared to have sighted peaks to the east of the Great Ice Barrier. There was little if any room for a connection between the Ross and Weddell seas. It looked like Penck was wrong.

Sir Clements Markham was particularly positive about Filchner's efforts. Although Markham did not recognise the scientific outcomes, the German's bravery appealed: âThere was no impenetrable pack for him. He put the ship's stem straight at it, somewhere near Weddell's furthest, and forced her through. After battling with the pack over 120 miles the ship came out into open water and land was sighted in 76°35' extending to 79°. There was an ice barrier to the westward.'

The Scottish were equally enthusiastic. On the scientific front Robert Mossman, who had been part of Bruce's team, remarked, âThe German Antarctic expedition under Dr. Filchner is the most recent, and in some respects, the most interesting, of expeditions in the Weddell Sea areaâ¦It was Dr. Filchner's intention to winter on this land and make sledge expeditions in a westerly direction with the view of testing whether Penck's theory of the division of the Antarctic continentâ¦was correct.' And, âApart from the discovery of new land, the drift of the ship demonstrated the general circulation of the air and ocean currents of the Weddell Sea area.'

The balloon releases showed the same sort of temperature inversion the British were finding in the Ross Sea, suggesting this was a common feature of the Antarctic, while the route taken by the

Deutschland

gave a remarkably clear indication that the Weddell Sea flowed in a clockwise gyre. The Germans thought that this was driven by a low-pressure system which sat over the region, driving the air currents and ice in a clockwise direction, parallel to the coastline. âThe ice fields follow these

air currents, although they are sometimes pushed slightly out of the general direction,' Filchner later wrote. âThey respond quickly, however, to temporary changes in the wind direction, so that the direction of the drift always corresponds to the direction of the wind. It seems that when the barometric minimum increases in intensity the winds drive the ice fields toward the nucleus of the depression and thus cause dangerous ice pressures.'

The practical result, Filchner argued, was that in the Weddell Sea the ice can be compressed into ever more fantastic shapes and contortions, threatening ships unfortunate enough to be caught in their grip. The

Deutschland

avoided being crushedâothers would not be so lucky.

It was in the broader field of oceanography that the Germans arguably made their biggest contribution to Antarctic science. The

Deutschland

probed below the surface from the start, making frequent measurements of the different properties of ocean water down through the Atlantic and across a range of depths. The observations resulted in a tome of data describing and mapping the changes in temperature, salinity, density and dissolved oxygen through the Atlantic Ocean, from 80°N to 78°Sâa most impressive achievement.

From Buenos Aires, Brennecke reported: âthe main result of our serial sections is the demonstration of a deep current in about 1500 m to about 3000 m of depth which comes from the North Atlantic toward the south and because of its high temperature and high salt content passes between the overlying and underlying layers' and âa northward moving current at about 1000 m (demonstrated through the salinity minimum)'. The latter, he argued, was identical to that found by

HMS Challenger

and the

Gauss

, and most probably originated at about 50°S, where it sank and headed north.

Brennecke's great insight, however, was made later, on the

continental shelf of the Weddell Sea, where he discovered that the water had very similar properties at all depths. He realised that the intense winter cooling of the surface produced such prodigious quantities of sea ice that large amounts of dissolved salt were being concentrated down below. The result, Brennecke argued, was that the density became great enough to cause the water to sink off the shelf and flow northwards along the sea bottom.

The upshot of all the

Deutschland

's measurements was the knowledge that there were four alternating ocean layers in the Atlantic, transporting warmer and colder water south and north respectively, with the Weddell Sea playing a central role. While crossing the Southern Ocean around South Georgia, Brennecke had also noted there was a sudden drop in the saltiness of the surface waters flowing north. The German oceanographer did not realise it, but he had just discovered the Antarctic Convergence. At around 50°S, it is probably the most reliable boundary for defining the start of the Antarctic region and the distinctive cold, frigid waters to the south. All the key elements of the Atlantic Ocean circulation system had been found.

Here was the first substantial evidence that the world's oceans were circulating, replenishing nutrient levels in the south, and the Antarctic was in the thick of it. But it would be a decade before the German oceanographer Wilhelm Meinardus would pull everything together and show how important these observations were in understanding the bigger picture. The new continent was not as isolated as had been thought. Unfortunately for Brennecke, he never saw his results completely worked up, dying in 1924.

And yet, for all his innovative research on the

Deutschland

expedition, Brennecke was not a pleasant chap, at least according to Filchner. The German leader later remarked in

Exposé,

âthe

arrogant Brennecke maliciously annotated my notices on the blackboard in the mess⦠he announced, talking down to me: “If you need advice and instruction please feel free. I represent rigorous science on board!”'

On their return to Germany, Brennecke wrote to Amundsen when he heard the Norwegian had invited Filchner to join him on an attempt on the North Geographic Pole. âWhen Amundsen visited me in Berlin,' Filchner recorded, âhe gave me Brennecke's letter to read then threw it into the fire with the words: “You Germans always have to foul your own nest! It is a pity for Brennecke that he should stoop to such denunciations, since I know better than that schemer who you are!”' With the onset of World War I, Filchner's chance to go with Amundsen to the Arctic disappeared.

Although the fallout from the expedition threatened to overwhelm its good work, the Germans undoubtedly revealed a tremendous amount about a largely unknown part of Antarctica. Filchner might not have reached the South Geographic Pole but he showed the first of many phantom Antarctic lands to be exactly what it was, a mirage, and discovered the southern limit of the Weddell Sea. More importantly, his expedition proved that the Antarctic played a major role in the circulation of the world's oceans.

But it was the final expedition of 1912 that, spurning the South Geographic Pole, aimed for the first complete scientific study of this new continent, and showed the way forward for Antarctic research. The Australasian Antarctic Expedition, led by Douglas Mawson and championed by Ernest Shackleton and Edgeworth David, would both bring home a wealth of data and become famous for its adventures.