1912 (42 page)

Authors: Chris Turney

The scientists of 1912 were only just starting to grapple with some of these issues. Although Wilson got the primitiveness of emperor penguins wrong, he was correct in thinking that they offer a significant insight into the origin of modern birds. With

the discovery in 1953 of deoxyribonucleic acidâusually shortened to DNAâscientists realised that the evolution of species is accompanied by changes in their genetic make-up. When two species arise from a common ancestor and go off on their own evolutionary pathways, differences in DNA accumulate. The changes in the genetic composition of a species are like the hands of a clock, each change equating to the tick of a molecular timepiece. These accumulating ticks can be used to calculate when a species evolved. The critical thing is to find out the rate at which genetic mutations take place.

This is where penguins come in. Penguins have arguably the best fossil record of modern birds around the CretaceousâTertiary boundary, sixty-five million years ago, a period best known for the extinction of the dinosaurs. The earliest fossil penguin evidence has been found in New Zealand, and dates back sixty-two million years, shortlyâgeologically speakingâafter the separation of Gondwanaland. These early fossils provide an important fixed point in time, not just for calibrating the rate of changes in penguins but across the whole genetic tree of birds, allowing major junctures to be dated.

The results are fascinating, not least because the popular early theory that penguins evolved from the extinction of the dinosaurs is wrong. There almost certainly was a dinosaur relative to birds. However, the genetic code shows that modern birds had a last common ancestor long before the end of the Cretaceous, with penguins separating from their next nearest living relative, the stork, around seventy-one million years agoâlong before dinosaurs became extinct. As Antarctica became cloaked in ice, species of penguins moved out along the circumpolar current to the subantarctic islands, and from there to other southern landmasses, reaching as far north as the Galapagos Islands a trifling four million years ago. For the penguins that stayed behind, the continent became a lot quieter.

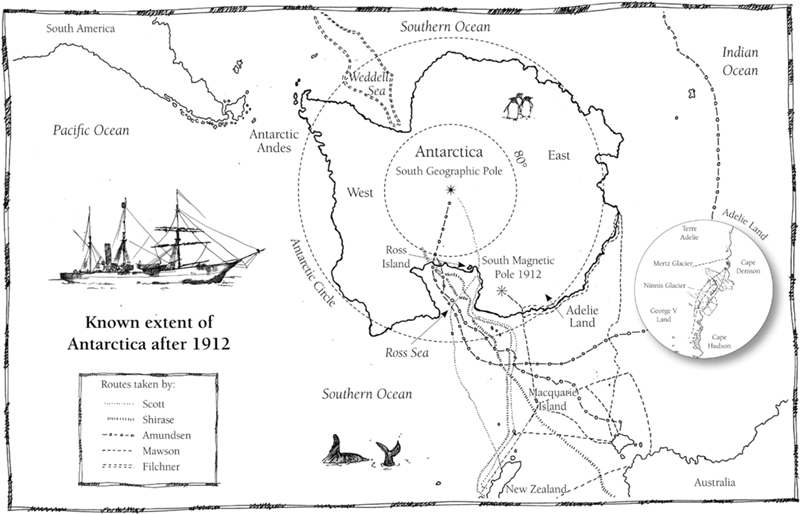

After the exploration work of 1912 Antarctica went from being an inaccessible land described in fantastical stories to being part of the real world. Before, the information gleaned had been sporadic. Now there were careful observations and hard data. A common misconceptionâas pervasive as the tall talesâthat Antarctica was just a land of white nothingness had been disproved, and with this the world's perception changed irrevocably. The southern continent was a staggeringly complex landscapeâand now there were more questions than answers. The expeditions of 1912 had shown the way, and it was only the beginning of the scientific work.

The Times

reported:

Now that the South Pole has been reached geographers will be free to carry on the investigations of this huge continent without any unpleasant element of rivalry, such as has existed hitherto in both ends of the earth. The expedition which started last year from Australia under Dr Mawson is the type of expedition that is to be encouraged in the future; and it is to be hoped that Dr Mawson's example will be followed by other explorers until the whole contour of this Antarctic Continent is mapped and such knowledge of its geographical, meteorological, biological and other conditions acquired as will satisfy the demands of science.

Mawson and Scott inspired fierce loyalty. From their efforts there emerged scientists dedicated to Antarctic affairs, who established research organisations and institutions that persist today. Debenham and Priestley helped found the British Scott Polar Research Institute in 1920; in Australia, Mawson succeeded in establishing the Australian National Antarctic

Research Expeditions, the forerunner of today's Australian Antarctic Division.

This enthusiasm for the south extended to protecting the continent itself, through the Antarctic Treaty. Enacted in 1961, this international agreement is now supported by forty-five signatories, and puts all territorial claims south of 60° on hold while preserving a nuclear- and mining-free Antarctic for future generations. The continent is now dedicated to science and explorationâa fitting tribute to those who undertook pioneering work and lost their lives on the ice.

By the first decade of the twentieth century rapid industrialisation was engendering a new form of confidence. The romance of civilised explorers battling against brute nature to unearth its hidden secrets captured a collective mood. And it was not entirely positive: this new swagger found articulation in the global power game of World War I.

The scientific explorations of 1912 proved an inspiration for the European youth of the day. Tales of ripping yarns and daring feats preached the value of self-sacrifice for the greater good. Poems drawing comparisons between the conflicts at Gallipoli and Flanders with the expeditions in Antarctica became widely known, while Ponting's original film of Scott's expedition,

The Great White Silence

, was shown to more than one hundred thousand officers and men of the British Army, with the photographer lecturing daily in London through most of 1914. The British tragedy in Antarctica struck a poignant note.

World War I resulted in the deaths of tens of millions of soldiers and civilians. Within these statistics lie the men to whom Shackleton dedicated his book

South

: those âwho fell in the white warfare of the south and on the red fields of France

and Flanders'. The Japanese declared for the Allies but it does not appear any of Shirase's men died during the fighting, while Norway remained neutral.

Of the other expeditions, however, one in ten of those who had served in and survived the extremes of the Antarctic did not live to see 1919. Many were mentioned in dispatches. Filchner's expedition lost two men to the war and Scott's three, while Mawson's two team members included Robert Bage who, after surviving a second winter in Antarctica, died during the first fortnight of the Australian campaign at Gallipoli. It was a terrible waste of life.

And it wasn't just men who were victims. The war suddenly created a large market for explosivesâin particular, glycerine, a by-product of whale-oil production. Antarctica's natural resources were tapped, ensuring the continent joined the modern world.

The first meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Australia was held on the verge of the conflict, in August 1914. The German scientist Friedrich Albert Penck was en route when war was declared. David defended Penck in the same way he had Shirase and his men in Sydney, speaking highly of the German and vouching for him while in Australia. The sentiment was not reciprocated; it seems Penck did spy for Germany during his visit, taking photos of harbour defences in the New South Wales city of Newcastle.

David went on to volunteer for the war effort, though he was fifty-eight, and became a major in the Australian Mining Corpsâbetter known as The Tunnellersâwhich he helped establish; his geological expertise proved crucial to the Allies efforts, most notably at the Battle of Messines in 1917, for which

he later received the Distinguished Service Order. It was yet another remarkable achievement in a remarkable career.

Ernest Shackleton went on to lead the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, hoping to cross the great continent for the first time, but met a similar fate to Filchner. Before he could make land, his ship, the

Endurance

, became locked in the Weddell Sea ice during 1915 and iconic images taken by Frank Hurley, fresh from his Antarctic mission with Mawson, immortalised the expedition as the vessel sank.

Shackleton led his men through the ice floes to reach Elephant Island at the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. Leaving most of the men under the leadership of Frank Wild, he proceeded to sail the thirteen hundred kilometres to South Georgia in a tiny boat. Becoming the first to cross the island's mountains, he then raised the alarm at a whaling station and returned to Elephant Island to find everyone alive. Yet again Shackleton lived up to his towering reputation.

During an expedition to the Antarctic in 1922, again with Wild, the great man died of a heart attack. He was only forty-seven. At his wife's request, Shackleton's body was buried at Grytviken in South Georgia, where today his grave looks over the cruise ships that visit the island.

Roald Amundsen returned north after celebrating his success at reaching the South Geographic Pole. But his dream of doing the same in the Arctic was frustrated. The

Fram

was badly rotted after its travels, so Amundsen had to build a new ship to drift over the poleâand the attempt failed, with the vessel missing the location. Amundsen later flew over the North Geographic Pole in the airship

Norge

, but after falling out with his brother Leon he struggled with money and was later declared bankrupt. Amundsen returned north yet againâin 1928, to help find a lost explorerâbut was sadly lost over the ice, dying aged fifty-five.

Nobu Shirase lived a considerably longer time, in relative poverty, spending most of his life paying off the cost of the Japanese expedition. Finally clear of debt he lived for a further decade, barely surviving on an army pension, and died in 1946, at the age of eighty-five. It was a shocking way to treat a man who claimed, with some justification, to have âkindled the latent fire in the hearts of the Japanese'.