1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War (12 page)

Read 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War Online

Authors: Benny Morris

BOOK: 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War

10.62Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The report described UNSCOP's work, the elements of the Zionist-Arab conflict and the contending claims, and surveyed previous proposals (including the Peel Commission report). There followed UNSCOP's unanimous recommendations, the recommendations of the seven-member UNSCOP majority, and the recommendations of the three-member minority. (Hood, the Australian representative, while leaning toward the Zionist case, abstained-probably in deference to the wishes of his government.)56

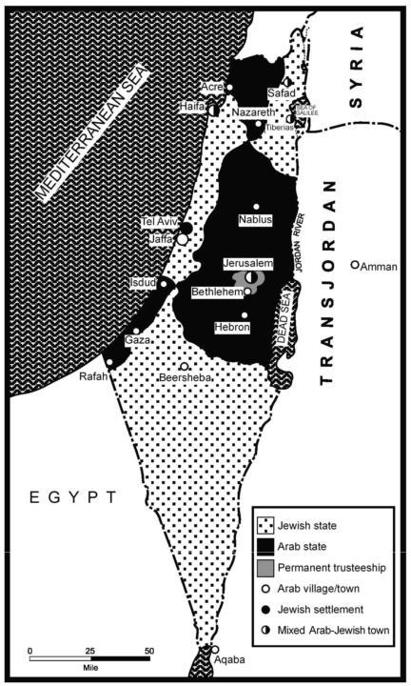

The chief unanimous recommendations were the termination of the Mandate at the earliest possible time and the granting of independence to palestine. The majority-the representatives of Sweden, Holland, Canada, Uruguay, Guatemala, Peru, and Czechoslovakia-proposed partition, with an enclave (a corpus separatum) under international control consisting of Jerusalem and Bethlehem. The Jewish and Arab states were to be bound in economic "union"-were to function as one economic entity-and the British would continue to administer the country for two years, during which iso,ooo Jews would be allowed into the Jewish-designated areas in monthly quotas. During the first year of independence the inhabitants of each state desiring to move to its neighbor would be free to do so. As it stood, the Jewish state, according to UNSCOP, was to have half a million Jews and 41 6,ooo Arabs, along with some ninety thousand bedouins who were not counted as permanent residents.57 The corpus separatum of Jerusalem-Bethlehem was to have a population of two hundred thousand, half Jewish and half Arab. The Arab state was to have some seven hundred thousand Arabs and eight thousand Jews. The proposed arrangement was described as the "most realistic and practical" possible.

The UNSCOP minority proposal, penned by the Yugoslav, Iranian, and Indian representatives, was for Palestine to be given independence as a "federal state," with locally governed, separate Jewish and Arab autonomous areas (which they confusingly called "states"). Its frills removed, the proposal charted the establishment of a unitary state under Arab domination, to be established after a three-year transitional period. Jewish immigration was to be allowed only to the two Jewish areas (limited to the Coastal Plain and part of the northern Negev)-and, overall, was to be curtailed by the federal authorities in a manner that always left the Arabs with a countrywide majority.58

The UNSCOP majority partition proposal, i September 1947

The UNSCOP majority arrived at their recommendations mainly because they could see no better alternative.sy The Zionists saw things more positively. They regarded the majority recommendations as a "giant achievement" or, in Ben-Gurion's words, "the beginning, indeed more than the beginning, of [our] salvation."60

The Arab reaction was just as predictable: "The blood will flow like rivers in the Middle East," promised Jamal Husseini. Haj Amin al-Husseini went one better: he denounced also the minority report, which, in his view, legitimized the Jewish foothold in Palestine, a "partition in disguise," as he put it. The Arab states, too, expressed dismay and negativity concerning the majority recommendations; "No Arab Government," Lebanese prime minister Riad al-Sulh told a British diplomat, "would dare to accept recommendations of U.N.S.C.O.P. Public opinion was now highly incensed and the Government[s] were forced to take some action ... or be swept away."61 According to Musa al- Alami, the Arab population of Palestine would rise up against both the majority and minority reports. In the case of the majority report, the rising would "command universal support"; as to the minority report, "the rising might still be fairly successful."62 Azzam, the Arab League secretary-general, reacted both passionately and analytically: "[To the Arab peoples] you are not an [existing] fact-you [the Jews] are a temporary phenomenon. Centuries ago, the crusaders established themselves in our midst against our will, and in 200 years we ejected them.... Up to the very last moment, and beyond, they [the Arabs] will fight to prevent you from establishing your State. In no circumstances will they agree to it." But Azzam added that, in the past, the Arabs had "once had Spain, and then we lost Spain, and we have become accustomed to not having Spain.... Whether at any point we shall become accustomed to not have a part of Palestine, I cannot say. The chances are against it, since 4oo,ooo of our brethren will be unwilling citizens of your State. They will never recognize it, and they will never make peace. "63

But UNSCOP had delivered its judgment. What could or would the Arab states do? While blustering, they generally acknowledged their military weakness. Adil Arslan, one of Syrian president Shukri al-Quwwatli's advisers, later minister of defense, jotted down in his diary: "Poor Palestine, no matter what I say about defending it my heart remains a seething volcano because I cannot convince anyone of importance in my country or in the rest of the Arab countries that it needs anything more than words.... Because we have a small and ill-equipped army, we cannot stand up to the Zionist forces if they should suddenly decide to launch a strike at Damascus."64

British diplomats were surprised by the absence of mass demonstrations in the Arab world.65 The British saw the majority report as grossly unfair to the Arabs (Alexander Cadogan, the UK's representative to the United Nations, commented: "The majority plan is so manifestly unjust to the Arabs that it is difficult to see how we could reconcile it with our conscience").66 Yet the official response was born of realpolitik, not moral qualms: the cabinet resolved, in a secret decision on 20 September, to quit Palestine completely; but the British would not enforce or shepherd partition. As Creech Jones, the colonial secretary, predicted, Palestine would be overtaken by "a state of chaos. "67 In other words, either the United Nations would set up the machinery for resolving the conflict and an orderly transfer of power or the Arabs and the Jews would settle the problem on their own, by force of arms. In either case, it was no longer Britain's responsibility.

THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY PARTITION RESOLUTION, 29 NOVEMBER 1947

On 26 September Creech Jones announced at the UN General Assembly, sitting as the Ad Hoc Committee on Palestine, that Britain planned "an early withdrawal." Over the next two months, on the basis of the UNSCOP recommendations, three specially appointed subcommittees of the Ad Hoc Committee hammered out the terms of the resolution to be submitted to the General Assembly.68

All sides mounted intensive lobbying campaigns. The atmosphere was overheated: "The whole of New York," of course, was "mad," "so vast, so dirty, so crushing to the individual," one Jewish Agency emissary reported.69 More to the point, for Walter Eytan, who had "studied the map of the United Nations very, very thoroughly"70 and now orchestrated the Zionist contacts at Lake Success (where the General Assembly was meeting), were the activities of the hostile British delegation, "held to be the ablest of all the delegations" in the international body.71 Moreover, Eytan was concerned about his own staff of Jewish Agency Political Department "diplomats" and the attached American Zionist officials-who, he said, were motivated by a "hunt after kavod [glory, honor], ambitions, considerations of prestige, etc.-all playing the major part in people's lives and minds. The number of tocheslecker [ass-lickers] surrounding Weizmann at present makes me sick."72 Nonetheless, the Zionists efficiently deployed their manpower, assigning an official with the appropriate language and diplomatic skills to "work" on each UN delegation: Eliahu (Elias) Sasson, the Aleppo-born Arabist, making contacts with the Syrians, the Yemenis, and the Iraqis; Moshe Toff (Tov), working with the Colombians, Ecuadorians, and Mexicans; the Russian-born Eliahu Epstein handling the Soviets; and the South Africanborn Michael Comay dealing with the South Africans, New Zealanders, and Australians.7s But there were ruffled feathers among officials assigned minor countries, such as "Luxemburg, Ethiopia and Liberia.... [They were] too foolish to realize that each of these countries has exactly as much of a vote as others with more important-sounding names."74

The Zionists suffered from violent mood swings. In late September it was "pessimism. 117S A fortnight later, they were buoyed by the American reiteration (on i i October) of support for the majority recommendations, despite a last-ditch struggle against partition by the State Department. The Soviet Union followed suit two days later. "We are not dissatisfied with the results achieved [so far]," reported Eytan, but he realistically cautioned: "I realize that there is many a slip twixt the cup and the lip, and we shall not start cheering until the whistle blows."76 On 13 November Britain announced that it would withdraw all its troops from Palestine by i August 1948.

It was Subcommittee One that translated the UNSCOP majority recommendations into the proposals that were approved by the General Assembly, as Resolution 18 i, on 29 November 1947. The prospective minorities in each state posed a major problem. The Zionists feared that the Arab minority would prefer, rather than move to the Arab state, to accept the citizenship of the Jewish state. And "we are interested in less Arabs who will be citizens of the Jewish state," said Golda Myerson (Meir), acting head of the Jewish Agency Political Department. Yitzhak Gruenbaum, a member of the Jewish Agency Executive and head of its Labor Department, thought that Arabs who remained in the Jewish state but were citizens of the Arab state would constitute "a permanent irredenta." Ben-Gurion thought that the Arabs remaining in the Jewish state, whether citizens of the Arab or Jewish state, would constitute an irredenta-and in the event of war, they would become a "Fifth Column." If they are citizens of the Arab state, argued Ben-Gurion, "[we] would be able to expel them," but if they were citizens of the Jewish state, "we will be able only to jail them. And it is better to expel them than jail them." So it was better not to facilitate their receipt of Jewish state citizenship. But Ben-Gurion feared that they would prefer this citizenship. Eli`ezer Kaplan, the Jewish Agency's treasurer, added: "Our young state will not be able to stand such a large number of strangers in its midst."77

Much of the lobbying and diplomacy surrounding Subcommittee One focused on the exact contours of the two states. In the end, Britain and the Arabs, assisted by the US State Department, managed to persuade the Ad Hoc Committee to reduce the size of the UNSCOP-proposed Jewish state.

The British and the State Department made vigorous efforts to consign the Negev-which the UNSCOP majority had earmarked for the Jews-to Arab sovereignty. The personal intervention of Weizmann with Truman, on 19 November, was required-as well, perhaps, as Truman's perception that the Negev represented for the Jews what "the Frontier" had represented for the Americans a century before78-to save the bulk of the desert for the Jews,79 though they had to give up Beersheba and a strip of territory along the Sinai-Negev border. In addition, Jaffa was removed from the prospective Jewish state and awarded to the Arabs as a sovereign enclave. The Jews were compensated with additional territory in the Galilee. With these changes to the original UNSCOP majority plan, the prospective Jewish state was reduced to 55 percent of Palestine, with a population of some half a million Jews and an Arab minority of around 450,000. (Another hundred thousand or so Jews lived in Jerusalem, which was to be part of the international zone.)

On a6 October, Zionist officials assessed that there were twenty-three votes for partition and thirteen against.s0 Matters slightly improved by 25 November, when Subcommittee One's report was finally adopted by the Ad Hoc Committee. The vote was twenty-five for, thirteen against, and seventeen abstentions. This was still short of the necessary two-thirds majority in the General Assembly.

The numbers triggered alarm bells in Jerusalem, and the Jewish Agency Political Department, assisted by local branches of the World Zionist Organization, embarked on a world-embracing campaign to bring in the votes. The campaign proceeded along two tracks: direct Zionist lobbying to persuade individual governments and indirect efforts to persuade Washington to pressure other governments to vote for partition. Both campaigns moved into high gear on 24-25 November.

On 23 November Jamal Husseini, the AHC representative, was optimistic (though another member of the Palestinian delegation, Wasif anal, seemed less so when he said, "The Jews are the most cunning people among the nations of the world and on top of that they have the means. They bribed most of the delegates, but we do not have the money to bribe" ).si The British estimated that there were "twenty-five-twenty-seven votes for partition and fourteen or fifteen against it";82 on 26 November, their estimate was "30 ... for partition ... [and] IS against," but this excluded "the Siamese delegation, which has disappeared, or the Liberian, which may possibly cast its vote with the Arabs."x" It was touch and go.

Direct Zionist lobbying focused both on the governments at home and the delegations in New York, and a range of arguments, incentives, and disincentives were brought to bear. The underlying argument was the two-thousandyear history of Jewish suffering and statelessness, culminating in the Holocaust, and the international community's responsibility to make amends.

Other books

Bliss by West, Maven, Hood, Holly

War 1812 by Michael Aye

Catch & Release by Blythe Woolston

Rhyn's Redemption by Lizzy Ford

Rage Is Back (9781101606179) by Mansbach, Adam

Blackstone's Pursuits by Quintin Jardine

Red Rain: Lightning Strikes: Red Rain Series #2 by David Beers

Fear God and Dread Naught by Christopher Nuttall

The Last Judgment by Craig Parshall

Metal Fatigue by Sean Williams