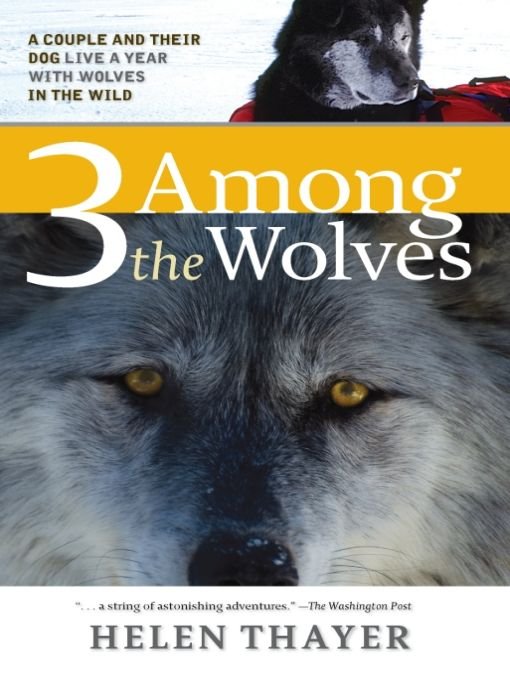

3 Among the Wolves

Read 3 Among the Wolves Online

Authors: Helen Thayer

Table of Contents

Â

Â

Â

Â

To the wolves who became our friends

To Charlie who made it all possible

Introduction

A

LONE IN THE WILDERNESS of the Canadian Yukon, my husband Bill and I zigzagged up a steep slope to a knife-edged ridge. After discarding our packs, we crouched among lichen-covered boulders to scan our binoculars across a remote meadow nestled in the valley below. Our hearts skipped a beat when we spotted them: two wolves, one black and one blond. The pair strolled into the open. Three more adults and four roly-poly pups soon joined them. Charlie, our part-wolf canine companion, stood unseen on a short leash at our side, silent and still, his gaze fixed on the pack. Undetected downwind, we three continued our secret watch.

LONE IN THE WILDERNESS of the Canadian Yukon, my husband Bill and I zigzagged up a steep slope to a knife-edged ridge. After discarding our packs, we crouched among lichen-covered boulders to scan our binoculars across a remote meadow nestled in the valley below. Our hearts skipped a beat when we spotted them: two wolves, one black and one blond. The pair strolled into the open. Three more adults and four roly-poly pups soon joined them. Charlie, our part-wolf canine companion, stood unseen on a short leash at our side, silent and still, his gaze fixed on the pack. Undetected downwind, we three continued our secret watch.

The black wolf, gripping a large stick between his teeth, began an energetic tug-of-war with the pups while the other four wolves flopped down in what seemed to be favorite places. After a few minutes the black wolf joined the rest of the pack, leaving the pups' game to deteriorate into a raging fight. A dark gray wolf darted out and, with a few well-placed nips on rears, ended the squabble. The chastised pups scurried behind the rocks into their den.

From the trampled meadow, a heavily used trail, embedded in the tundra, snaked into a grove of stunted spruce trees. Two more trails switchbacked to the rocky summit of a steep slope. The den we had been seeking for the past eight weeks was dug into its base.

As Bill and I rejoiced at our discovery, howls suddenly erupted from the distant tundra beyond the trees. All the wolves

jumped to their feet to stare in the direction of the sound, waving their tails expectantly. Soon five more adults emerged from the trees, dragging behind them the partly eaten carcass of a white Dall sheep. The pack greeted the hunters excitedly, licking their muzzles. A large male regurgitated partly digested meat for the pups, while the rest of the family ripped apart and eagerly consumed the sheep. After eating his fill, the black wolf climbed to the summit and sat with his back to us.

jumped to their feet to stare in the direction of the sound, waving their tails expectantly. Soon five more adults emerged from the trees, dragging behind them the partly eaten carcass of a white Dall sheep. The pack greeted the hunters excitedly, licking their muzzles. A large male regurgitated partly digested meat for the pups, while the rest of the family ripped apart and eagerly consumed the sheep. After eating his fill, the black wolf climbed to the summit and sat with his back to us.

As we counted the wolvesâsixteen altogetherâCharlie tugged at his leash and took a step forward. Pointing his muzzle to the sky, he gave a long howl. The black wolf leaped to his feet and spun to face Charlie, who dropped silently to his belly, laying his head on his paws. He kept his eyes below those of the wolf, looking downward to display submission and respect.

We expected the wolf to retreat out of caution, but instead he returned Charlie's howl. The blond wolf sped up the trail to the black one's side. Now both stared at Charlie.

Charlie raised his muzzle and howled again. The pair stood tall and alert, with tails curled above their backs. In unison, both returned Charlie's call. Then they bounded downhill to rejoin their pack. The rest of the wolf family was guarded but calm, watching Charlie, who gazed back, relaxed but vigilant.

Still hidden, Bill whispered, “We should leave.”

To mark the den's location on our map, we quickly took a reading with our global positioning system (GPS). Then we crouched low and began to creep away silently, still downwind. Charlie followed at first, then stopped to look back. With an urgent tug of his leash I whispered, “Come on.” We didn't stop or straighten up until we were well out of sight.

After two more miles of trekking across steep slopes and uneven tundra, we arrived at our camp, where we took another position reading to record our tent site in our journal notes. We would use these readings to locate the den when we returned

next summer, equipped and ready to attempt to live among these wondrous creatures.

next summer, equipped and ready to attempt to live among these wondrous creatures.

In our thirty-two years of marriage, Bill and I had worked together on more than twenty expeditions. He was a helicopter pilot who had amassed almost 13,000 flight hours during a career spanning four countries: New Zealand, the dense jungles of Guatemala and Honduras, and the United States, where he was a bush pilot in Alaska's mountains. My love of outdoor adventure had begun early, at nine years of age, when I began climbing mountains in my home country of New Zealand. As I grew older, I challenged myself with more technical routes and also competed as a discus thrower for New Zealand, Guatemala, and the United States. Later, in 1975, I won the U.S. national luge championship and represented the United States in European competition.

But the mountains were my first love. In 1986 I decided to embark on a series of expeditions to the world's remote regions. Journeys with Bill included kayaking 1,200 miles through the Amazon rain forest and trekking 2,400 miles through the Sahara Desert. Closer to our home in the northwestern United States, we had explored 1,500 miles of the Mojave and Sonoran Deserts. In 1997 I trekked solo in Antarctica, and Bill and I walked 1,450 miles across the Gobi Desert of Mongolia in 2001.

In 1988, in celebration of my fiftieth birthday, I became the first woman ever to complete a solo trek to the magnetic North Pole. The trek was just one element of my quest to create a continuing educational series called Adventure Classroom that would enable me to share the challenges and wonders of the world with students of all ages, worldwide, through websites, lectures, and books.

The success of the first program encouraged me to join with Bill in a second journey on foot to the Pole four years later, again without dog teams or snowmobiles. Between these two polar journeys, we spent many months exploring remote areas in Alaska and in Canada's Yukon Territory, the Northwest Territories, and Nunavut, where we encountered repeated examples of wolves coexisting with other creatures. Seeing such cooperation piqued our curiosity.

The Richardson Mountains where we hope to find a wolf den, as viewed from Eagle Plains.

As we trekked with caribou during their spring migration in Alaska, for instance, we observed wolves following the Western Arctic caribou herd as the almost half-million animals streamed north to their calving grounds on the North Slope. Similarly, in Canada we watched wolves following the Porcupine caribou herd as they traveled about four hundred miles from the Canadian Yukon to their calving area in Alaska's Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. During previous expeditions in the northern polar regions, we had observed wolves and arctic foxes following polar bears in apparent harmony with each other.

I had been fascinated by wolves for many years, but it was Bill who really began studying wolves in the wild. While flying a helicopter as a commercial bush pilot in Alaska, he had seen many wolves at their dens and watched them as they pursued prey across the tundra, and had developed a lasting respect for the animals. Although usually soft-spoken and somewhat reserved, he had felt compelled to speak to Alaskan government agencies repeatedly concerning the need to protect wolves from aerial hunters, who sought to destroy entire wolf families by shooting them from planes. As his protests continued to go unheeded, he became even more determined to work toward a better understanding of wolves and their environmental importance.

These experiences led us to dream of a new program for Adventure Classroom, one in which we would explore the intertwined relationship of the gray wolf species (

Canis lupus

) and the other animals who share the wolf's habitat, from grizzly bears to caribou. Gray wolves inhabit parts of North America, Europe, and Asia. A symbol of the wilderness, they are astute hunters, socially complex, family oriented, with strong nurturing instinctsâin many ways like our good friend the dog, but also cannily like humans. Perhaps our similarities are the reason wolves have often taken center stage in the human imagination and today stir strong emotional debate over their place in the world.

Canis lupus

) and the other animals who share the wolf's habitat, from grizzly bears to caribou. Gray wolves inhabit parts of North America, Europe, and Asia. A symbol of the wilderness, they are astute hunters, socially complex, family oriented, with strong nurturing instinctsâin many ways like our good friend the dog, but also cannily like humans. Perhaps our similarities are the reason wolves have often taken center stage in the human imagination and today stir strong emotional debate over their place in the world.

Other books

Ride the Thunder by Janet Dailey

We Can Laugh Together Too (Walnut Grove Trilogy) by Baker, Cindy

New Australian Stories 2 by Aviva Tuffield

El hombre de la máscara de hierro by Alexandre Dumas

Maxine by Claire Wilkshire

Emily: Sex and Sensibility by Sandra Marton

Rode Hard, Put Up Wet by James, Lorelei

Seize the Night: New Tales of Vampiric Terror by Kelley Armstrong, John Ajvide Lindqvist, Laird Barron, Gary A. Braunbeck, Dana Cameron, Dan Chaon, Lynda Barry, Charlaine Harris, Brian Keene, Sherrilyn Kenyon, Michael Koryta, John Langan, Tim Lebbon, Seanan McGuire, Joe McKinney, Leigh Perry, Robert Shearman, Scott Smith, Lucy A. Snyder, David Wellington, Rio Youers

No Safe Secret by Fern Michaels

Never Buried: A Leigh Koslow Mystery by Edie Claire