3 Among the Wolves (27 page)

Read 3 Among the Wolves Online

Authors: Helen Thayer

As we approached a twenty-foot-high pyramid of sparkling blue ice, Charlie stopped and yipped several times. Puzzled because the sound was different from his usual bear-warning bark, we allowed him to pull us around to the other side.

We froze, astonished. Two hundred feet away was a group of eleven wolves, all of whom we had seen on and off since leaving land. Smudge, whose behavior now confirmed that he was a family alpha, had already detected our approach. Stiff-legged, hostile, lips pulled back in a snarl, he stood in front of his family, ready to defend them.

Close behind him, the limping female hurried to join Blondy, who shielded her protectively. The others, including Crab and Patch, watched and paced nervously, never taking their eyes off us. Charlie squatted on his haunches, while Bill and I hastily sat on our sleds and looked away to show that we weren't a threat. Then Smudge and Blondy joined in a series of barks in varying tones, interspersed with growls through bared teeth, designed to keep us away.

Charlie dropped to his belly with his muzzle averted, touching the ice. Led by Smudge, the entire family abruptly galloped another hundred feet away to cluster behind two foot-high chunks of ice, then turned to watch us suspiciously. We slowly rose, turned our sleds and, with Charlie at our side, retreated the way we had come, swinging wide onto open, flat ice. Although we were now farther away, we still had an easy view of the family. Once again we sat on our sleds while Charlie lay on his belly on the ice, his head half-turned away in submission.

We had disturbed the group as they rested in a place they frequented regularly, judging by the many patches of urine-discolored snow and the numerous wolf scats nearby. After a fifteen-minute standoff the wolves, although still cautious, relaxed their stiff-legged posture. Smudge barked a short warning with no sign of his earlier bared teeth and growling. Charlie, still belly down on the ice, raised his head and replied with yips so soft even we understood they were benevolent.

At first there was a long silence. Perhaps Smudge was trying to judge this black, doglike wolf offering friendship. Then he replied with a few gentle yips, the last one ending on a penetratingly high note. The group gathered about their leader in a tight bunch, and he calmly led them away. They disappeared into an area of rough ice to the north. The limping female easily kept up, her limp barely perceptible.

As they turned away, Charlie stood and tried to follow until his leash stopped him. With a tug, he urged us forward. “No, Charlie, not this time,” I said quietly, as we headed west toward Pullen Island.

Meeting the sea ice wolves as a family answered a question that had increasingly bothered us. Why were we encountering so many wolves in a place where we would have considered ourselves lucky to see one or two? Even in our most optimistic mood, we had never imagined discovering an entire family.

We judged this spot to be a temporary resting site used by these wolves when open leads of water provided hunting bears with access to the area. Once the leads froze or shut, the bears would move to another area of open water, and the wolves would follow. Just as Alpha would be leading his pack across the southern tundra throughout the winter to hunt over a wide range, Smudge was leading his family on a journey across the frozen ocean. They had cleverly discovered that hunting was easier if they followed bears and shared whenever they could.

During the spring ice melt, the wolf family would be forced to abandon the ice and return to land. If a female was pregnant, they would dig a den or return to an old one, just as the summer wolves had done. The wolves in this pack, generally much lighter in color than Alpha's family, were about the same individual size. Smudge exhibited total control of his group as he led them to safety, his proud and imposing bearing reminding us of Alpha.

A shadowless fog swirled about us as we neared Richards Island, slowing our progress to a blind crawl. We could scarcely see our outstretched hands. Depth perception had disappeared. We drifted in a silent void where east and west, north and south, up and down were all the same. Slowly we moved in what we hoped was the right direction, gambling that our ski tips wouldn't drop into a watery abyss. The islands lay somewhere ahead, we thought. Engulfed in white, I stopped and shook my head to rid myself of a wave of vertigo.

“I hardly know whether I'm standing up straight,” Bill said, straining to see ahead. “I feel as if I'm floating.”

In our diminutive ice world, where we could see no more than a foot in any direction, each step was an adventure, like walking on a cloud. Even the ice underfoot was obscured by fog. We stumbled in the hollows and tripped on raised chunks of ice.

When I belatedly checked our direction on my compass, I discovered that instead of traveling northwest, we were skiing due south. We had traveled in a circle and were headed back toward land. I was leading and had made the foolish mistake of assuming that I knew the right direction. Bill kindly remained silent as I slipped the compass into a holder at my waist to make it easier to stay on course.

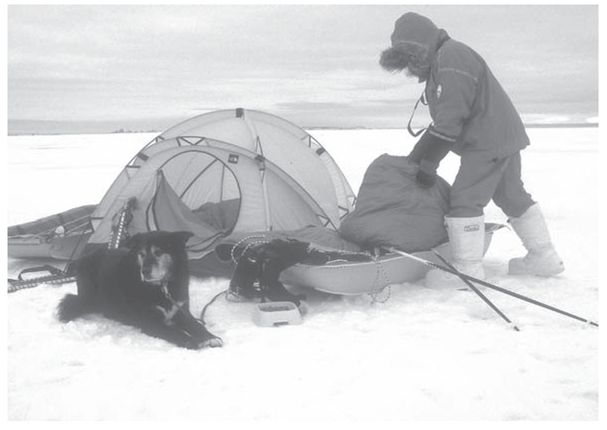

Charlie rests while we set up camp on the sea ice.

“I hope polar bears don't like fog and stay home,” I said nervously. More than ever, we would have to rely on Charlie to warn us.

An elated Charlie picked up the scent of polar bear tracks. He pulled out all the stops, with all manner of yips and tugging on his leash, to persuade us to follow the scent, but we insisted on a northerly course, away from trouble. He reluctantly agreed, but dropped back to follow on our heels with head and tail down to show his displeasure. After a half mile he was in front again, though, his gait buoyant and confident, his gaze ahead intense. No doubt he was hoping for more bear scents and sightings, while we were hoping all the area's bears were many miles distant.

We half-expected a bear to emerge suddenly from the ghostly fog as we skied slowly ahead. Twice Charlie halted us on the edges of cracks several feet wide. In the whiteout we couldn't see them, but he sensed the open water in time to stop. We groped our way around detours onto solid footing, thankful Charlie was along to save us from falling into unseen water.

Seven nerve-wracking hours later, our boots crunched across thin coastal ice. In a world still no more than two feet wide, our GPS unit faithfully confirmed our position: We had arrived at the northernmost tip of tiny Pullen Island. Judging by the fragile ice underfoot, we had practically gone ashore.

We peered into the swirling whiteness at something long and bleached white. Further investigation showed the object to be a weather-beaten log. At first it made no sense in that treeless place. Then we remembered that logs from southern forests float down the Mackenzie River. Upon reaching the Beaufort Sea, swift ocean currents sweep them west until Arctic storms cast them onto the northern shores.

We retreated to more stable ice to set up camp as dusk darkened our claustrophobic world. We were relieved to escape into our tent, where we could look at something besides the blank whiteness of the fog.

There was no wind. For once the ice was still. Before sliding into our sleeping bags for the night, we checked outside but could see nothing. Alone in the Arctic darkness, I felt a brooding mood descend upon our tent. I wondered aloud whether the bears would be kind enough to keep their distance tonight.

“No use worrying about them when we can't do much about it,” said Bill.

“Well, I'm not going to allow them to ruin a good night's sleep,” I said. I definitely did not want to sleep in two-hour shifts as we had before. Bill and I are both day people, and I always found it particularly difficult to stay awake during night watches.

Even the threat of polar bears was sometimes not sufficient to keep me awake. Bill claimed that I fell asleep on my feet.

Even the threat of polar bears was sometimes not sufficient to keep me awake. Bill claimed that I fell asleep on my feet.

Although troubled by the fog and bears, we rested well for the first two hours. But then Charlie suddenly rose and listened at the door. Bill opened the zipper, which sounded loud in the perfectly still night. Perhaps Charlie needed to relieve himself, I thought, but he didn't move. His head turned to his right, then slowly moved to his left, as though following something unseen.

We had learned long ago to respect Charlie's reactions around bears. Now we remained quiet, although my pounding heart felt as though it was about to leap out of my chest. My brain silently screamed,

Is there a bear out there?

Both Bill and I carefully reached for our shotguns. In cold climates, we don't keep firearms in the tent. Any condensation in the firing mechanism would freeze, rendering the weapon useless. Instead we leave our guns in the cold vestibule, with a portion of the butt barely inside the door. We made slits in the door at floor level for just this purpose.

Is there a bear out there?

Both Bill and I carefully reached for our shotguns. In cold climates, we don't keep firearms in the tent. Any condensation in the firing mechanism would freeze, rendering the weapon useless. Instead we leave our guns in the cold vestibule, with a portion of the butt barely inside the door. We made slits in the door at floor level for just this purpose.

After five or ten minutes that seemed like forever, Charlie relaxed. His tail fanned back and forth, and after two yips he spread himself out on my sleeping bag with a contented sigh to resume his sleep. The episode was over for him, but we, still clutching our shotguns, continued to listen to the deep silence and its echoes in our imaginations.

Soon, though, the biting cold sent us back to our sleeping bags. “It had to be a bear. But Charlie seemed to send a friendly signal,” Bill whispered, as though afraid any noise might attract an unwelcome guest.

I agreed, still feeling exposed and vulnerable to whatever had caught Charlie's attention. We were puzzled by his friendly reaction, which was more in keeping with greeting a wolf than a polar bear.

Sleep came only fitfully for the rest of the night. Dawn greeted us with the same silent mist. Hoping it might lift, we

waited. But after several of the most boring hours of the expedition had passed, there was no improvement. At least in a storm we could listen to the wind. Here the only sound was the cracking of the ice pack as it moved. After a short discussion, we decided to begin our trip back to the mainland and hope conditions would clear. Although sorry to miss seeing Richards and Pullen Islands up close, we felt unsafe lingering amid so many bears.

waited. But after several of the most boring hours of the expedition had passed, there was no improvement. At least in a storm we could listen to the wind. Here the only sound was the cracking of the ice pack as it moved. After a short discussion, we decided to begin our trip back to the mainland and hope conditions would clear. Although sorry to miss seeing Richards and Pullen Islands up close, we felt unsafe lingering amid so many bears.

As I loaded my sleeping bag onto the sled, I looked down. Right beside the runners was a large set of polar bear paw prints and two sets of wolf tracks that continued right past our tent, only three feet in front of the door. Now the nighttime picture was clear. When Charlie had listened so intently he must have known there was a bear outside, but his yips had been a greeting to the two wolves following the bear.

Bill agreed, but wondered just how far the bear had traveled and in which direction. Might he still be nearby? Charlie showed no sign of scenting a bear, but Bill was taking no chances. “Just in case they didn't go far, let's get out of here,” he said.

We packed our sleds in record time, attached skis to boots, buckled our harnesses around our waists, and set off. Movement might give us a false sense of security, but it was better than contemplating a dubious future in the claws and jaws of a hungry polar bear.

Charlie displayed no such fear. His calm demeanor embarrassed us as we hurried away from the ghostly forms we imagined in the fog. He walked placidly ahead of me, knowing all was well and perhaps wishing his humans would get a grip on their emotions.

As we followed the compass needle southeast, leaving the shoreline of the island, the fog continued to thicken. The presence of bears and heavy fog made us suspect there was a much larger expanse of open water close by, possibly to the north.

As we travel side by side through life, Bill and I make a solid team.

Fog forms when frigid air temperatures meet warmer water. Because of the constant movement of the sea ice, wide cracks and sometimes persistent or permanent areas of open water exist in both summer and winter. Called “polynyas,” and caused by currents, wind, and warm upwellings, these are treasure chests of wildlife, including seals. And of course, where there are seals, there are polar bears. Thus our surroundings provided plentiful clues about the conditions ahead.

Other books

Silent Thunder by Andrea Pinkney

Autumn Bridge by Takashi Matsuoka

Graceful Submission by Melinda Barron

Accidentally...Evil? (Accidentally Yours) by Pamfiloff, Mimi Jean

Here Come the Girls by Johnson, Milly

Hiding His Witness by C. J. Miller

Business of Dying by Simon Kernick

Good Graces by Lesley Kagen

Call of the Wild Wind (Waterloo Heroes Book 2) by Sabrina York

I Am Juliet by Jackie French