(3/20) Storm in the Village (26 page)

Read (3/20) Storm in the Village Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Fiction, #England, #Country life, #Country Life - England, #Fairacre (England : Imaginary Place)

I steered the conversation to the state of Miss Clare's health and her hopes for the future.

'Everyone worries far too much about me,' she said gently. 'I think I shad be able to manage here for some time yet. And I must say, that with Miss Jackson looking more cheerful, the outlook is much more hopeful for me. It's just at night sometimes——' Her voice died away and she looked into the fire. Taking a deep breath I unfolded my proposals.

Miss Clare listened in silence. When I had finished, she leant forward and took my hand.

'I can't thank you enough, but I'm going to tell you something. George Annett has promised that if ever Miss Jackson leaves me he will find a really easy lodger from his own school to take her place—so that I have no financial worries. And if my health should fail, and I have to leave this little house, he and Isobel have another plan. But I won't speak of that. I hope I may be here for many years.'

She bent down and put two logs of apple wood on the fire. Their sweet outdoor fragrance began to creep about the firelit room.

'For a woman who loves solitude as much as you do,' she continued, 'and who gets so little of it—I think you have made a superhuman offer. But I don't think the need will arise for me to accept such kindness.'

'It will stand anyway,' I told her truthfully. Miss Clare stood up.

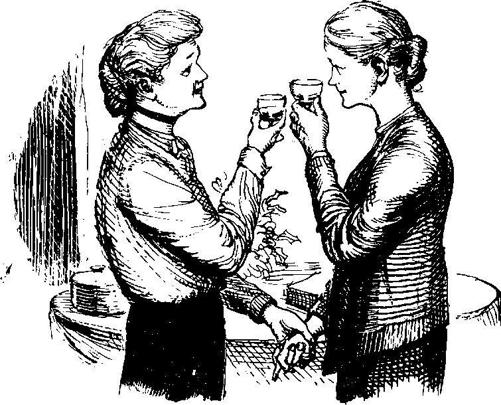

'Have a glass of home-made wine,' she said briskly. She went to a corner cupboard, high on the wall, and produced a deep red bottle that glowed like a ruby.

'Plum,' she said with satisfaction, 'and two years old!'

She trickled it into two wine glasses, brought mine over to me, and then raised her own.

'I'm thinking of Hilary's remark,' she said. 'To our friends!'

We sipped, smiling at one another.

22. Fairacre Waits and Wonders

T

HE

Nativity Play, which took place in St Patrick's church three days before Christmas, had occasioned almost as much comment as the proposed estate. This was the first time such a thing had been attempted and the innocent vicar, whose only thought had been of his parishioners' pleasure in praising God in this way, would have been flabbergasted could he have heard some of the criticisms.

'Nothing short of popery!' was Mr Willet's dictum. 'Play acting in a church! I don't hold with it!'

'It's been going on for years,' I pointed out mildly. 'Churches were used quite often to perform plays for the people.'

'When?' asked Mr Willet suspiciously.

'Oh, a few hundred years ago,' I replied.

'Then it's about time we knew better,' was Mr Willet's unanswerable retort.

The children had been practising their part in it for several weeks, and I knew that Mr Annett as choirmaster had been busy with the singing which was to form part of the play. Several parents had spoken to me, rather as Mr Willet had, expressing their grave concern about what one called 'doing recitations in the Lord's House.' The singing passed without comment.

But on the evening in question Fairacre's villagers turned up in full force and it was good to see the church packed. A low stage had been erected at the chancel steps and the setting was the stable at Bethlehem.

The church looked lovely, decorated for Christmas with holly wreaths and garlands of ivy, mistletoe and fluffy old-man's-beard. On the altar were bowls of Christmas roses and white anemones. Only candlelight was used that evening, and the golden flames flickered like stars here and there in the shadows of the ancient church.

The play was simple and moving, die country people speaking their parts with warm sincerity, but it was the unaccustomed beauty of the boys' singing that was unforgettable. Mr Annett had wisely set aside several passages for the boys alone and their clear oval notes echoed in the high vaulted ceiling, with thrilling beauty. Whatever may have been said about such goings-on in church before the play, everyone agreed, as they stopped to talk afterwards in the windy churchyard, that it was a moving experience.

'The vicar could've done a lot worse,' conceded Mr Willet. And that indeed was high praise.

The holidays slipped by with incredible speed and early in January I was facing the school again at our first morning of the New Year.

There were thirty-six children now on rod and I wondered, as I watched them singing, how many I should see before me at the same time next year. Would ad these older children, now making the partition rattle with their cheerful voices, have been wrested from Fairacre and be adding their numbers to those at the new school, standing on what had once been Hundred Acre Field? Would I have a handful of infants, and remain here, the sole member of staff, with one of the rooms empty of children after nearly eighty years? It was a depressing and disturbing thought and it had occurred to me more often than I cared to admit to anyone. This was my life, as satisfying and rewarding as ever a woman could ask for, and the thought of change distressed me.

Mr Willet would say 'Cross that bridge when you get to it!' I told myself, and I put these upsetting conjectures from me resolutely and determined to live for the day alone, although it was not easy.

Miss Jackson had returned in high spirits. Miss Crabbe was now in the ascendant, and had evidently done her best to make die girl forget the unhappy love affair which had so unsettled her. She told me some interesting news.

'Miss Crabbe is starting a small school this summer. It's to be a kindergarten school quite near the college and she's running it on progressive lines, of course.'

'Of course,' I echoed gravely.

'She's got two other friends who are helping her with the money-people who are

quite sure

that her teaching methods are revolutionary—and she's asked me if I would like to be appointed to the staff.'

'And would you?' I asked unnecessarily. Hilary's face was radiant.

'I can't think of anything that I'd like more. There will be a house attached as there are going to be a few boarders—the ready difficult cases—and I should live there with Miss Crabbe. Won't it be lovely?'

I said that it sounded a most hopeful venture and thought, privately, what a good thing it would be for the girl to get into another new post after ad that had happened in Fairacre.

'She wants to open it next September and is already getting out prospectuses.'

'Then you'd have to give in your notice here about Eastertime,' I said.

'That's right,' agreed Hilary ecstatically. 'It will ad fit in quite well, because by that time I expect the older cruldren will have been sent on to the new school, and you won't need an assistant with just the infants.'

I was a trifle shaken by this calm acceptance of Fairacre's future plans, and hastened to point out that even if the estate were built, the school could not possibly be ready to house children by next September.

'In that case,' said Miss Jackson off-handedly, 'they would have to get another teacher in my place.'

'I suppose so,' I agreed. For one dreadful minute my old doubts engulfed me again. Supposing that there was no assistant to be had this time? Could I tackle the whole school for any length of time? Could I even tackle the infants if the older children had been whisked away-to Beech Green perhaps-if the new school were not ready? Would it be best for everyone if I tendered my resignation too? I thought of all the tedious business of writing out testimonials, filling in endless forms, asking people if they would stand as referees. I thought too of ad that Fairacre and its folk had come to mean to me. No, I told myself firmly, I couldn't face it. For Fairacre's good or not, I should do my best there, and be happy to stay if I were deemed fit for the job. I came back to earth from this swift day-dream to hear Miss Jackson speaking with great earnestness.

'I couldn't let Miss Crabbe down, you know. It would be unthinkable!'

It seemed to me, in the weeks that Mowed, that Miss Jackson's acceptance of the housing scheme, as a foregone conclusion, was shared by others in Fairacre and the neighbourhood. It was as though the prolonged waiting had numbed the anti-estate feeling which has been so ferocious earlier in the affair. The people had lived with the idea for so long now that a fatalistic resignation to what might transpire had affected quite a number of them.

'We must get a more efficient heating system in the church if we have to house the new people,' said the vicar to his wife. 'The back of the church is never ready warm.'

Til have to think of an extra delivery van and an extra driver, this time next year,' said Mr Prince, the baker, to his assistant.

Even Mrs Pringle was beginning to soften towards the project.

'Poor things must live somewhere!' she pointed out reasonably. 'Do 'em good to get out into decent houses and a bit of fresh air!' From the way she spoke one might imagine that they were living, at the moment, huddled together in sewers.

But the flame still burned brightly in some breasts. Over at Springbourne old Mr Miller looked out at his unchanged view and the first tiny spears of his new crop in Hundred Acre Field.

'They'll not shift me!' he said grimly to his wife, wagging his frosted head. 'We'd still be here when they've gone elsewhere, mark my words!'

The vicar, on hearing that Mr Miller had planted his field as usual was much impressed and said so to old Mrs Bradley who was present at the time.

'It is an act of faith, dear Mrs Bradley. A true act of faith!'

'Plenty of spunk there,' agreed Mrs Bradley spiritedly. 'Keep fighting! That's the way to gain your ends, and fight with ad the weapons you can find! I myself sent a telling Christmas card to the Minister at his home address.'

'Ready?' said the vicar, somewhat alarmed. He would not have put sending a bomb past this fierce old lady.

'A reproduction of "The Dew Pond on the Downs",' continued Mrs Bradley. 'One of Dan's best pictures. And I signed it "Adelaide Bradley—Lover of Fair Play and Our Downs" and added "Remember Dan Crockford!" for good measure!'

'It may wed have helped,' said the vicar politely.

'Too much waiting about is making far too many fainthearts,' announced Mrs Bradley shrewdly—'"Up and at em" is my motto! We'd see 'em off yet!'

Amy brought much the same news of Caxley's reaction to the scheme when she came to spend an evening with me. Resentment had largely been replaced by a philosophic acceptance of the affair as a necessary evd, and, in fact, the shopkeepers were beginning to speculate on the increase in their business which so many extra families must inevitably bring.

Amy herself, however, was as militant as Mrs Bradley.

'I've sent four letters already to the

Caxley Chronicle

and two more to

The Times

about this business,' she asserted.

'I haven't seen them,' I said innocently.

'For some reason they haven't been published yet,' replied Amy, not a whit disturbed, 'but it's the

writing

that matters. We mustn't give way and let things slide. Which reminds me!'

She scrabbled in her large crocodile handbag, a gift from James after a week's absence at a mysterious conference at a place unspecified, and handed me a book.

'It's a lesson to you!' said Amy firmly. 'It's about a woman, living alone, just as you do, on a small income with a regular working day, who never Lets Herself Go! It impressed me very much. Quite a nice little love-story too,' added Amy, in a patronising tone.

'Any picture strips?' I asked acidly, putting the book on my shelf.

'It's that sort of remark,' said Amy coldly, 'that reveals what a frustrated woman you ready are!'

'That be Mowed!' I answered inelegantly. 'Don't come the Integrated-Married-Woman over me, my girl. I've known you too long. What about scrambled eggs on toast for supper?'

United in common hunger we went cheerfully together to raid the larder.

23. The Village Hears the News

M

ARCH

that year was one of the coldest that Fairacre had ever known. The nights were bitter, and cottage fires were kept in overnight with generous top-sprinkling of small coal dampened with tea leaves, and stirred into comforting life first thing the next morning.

Ad growth was at a standstill. The small buds on the hedges were brittle to the touch and the spearlike leaves of those hardy bulbs which had already sent them aloft grew not a whit. The birds were particularly hard hit and not a day passed without a child bringing in a small pathetic corpse, its frail claws clenched stiffly in its last agony.

The vicar grieved over the inadequate heating of St Patrick's. Mr Roberts, Mr Miller and all the neighbouring farmers chafed at the delay to their crops, the children came to school wrapped up like cocoons in numberless coats and scarves, and I suffered my seasonal stiff neck from the draught from the skylight above my desk.

Despite continuous stoking, on my part, of the tortoise stoves, the school seldom seemed ready warm because of villainous draughts from ill-fitting doors and windows. The coke pile in the playground began to dwindle visibly and Mrs Pringle was affronted.

'Good thing the Office can't see the rate we're using up the fuel!' she said darkly.