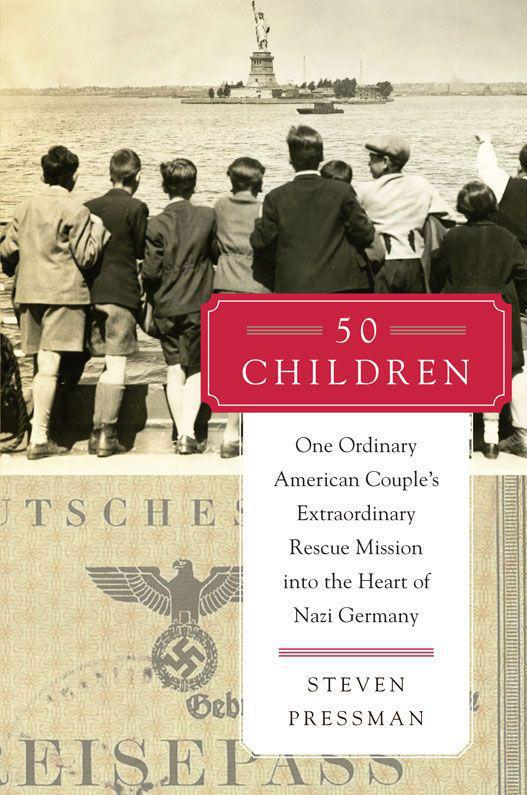

50 Children: One Ordinary American Couple's Extraordinary Rescue Mission into the Heart of Nazi Germany

Authors: Steven Pressman

Tags: #NF-WWII

F

OR

L

IZ

,

WHO ALWAYS KNEW

Whoever saves a life, it is considered as if he has saved the entire world

.

—T

HE

T

ALMUD

Contents

T

he inch-thick stack of yellowing onionskin paper rested in a brown cardboard binder held together by a rusting metal clasp. For years my wife, Liz, had kept it tucked away, half forgotten, in a desk drawer in our home in San Francisco, mixed in with the usual assortment of bank statements, medical records, and other household documents. But there was nothing even remotely mundane about the astonishing tale that had been carefully typed out on those brittle pages decades earlier. The contents of a small plastic bag, wedged between the manila file folders in the same desk drawer, added graphic drama to the pages in the binder: more than a dozen German passports, each stamped with a menacing Nazi swastika and bearing the name and photograph of a young girl or boy.

The broad outline of what Gil and Eleanor Kraus, my wife’s maternal grandparents, had accomplished in the spring of 1939 was not exactly a secret. Family members had long been aware of the couple’s daring voyage into Nazi Germany on the eve of the Holocaust and their return to the United States with fifty Jewish children in their care. For the rest of their lives, however, neither of them spoke in any detail with family or friends about their unlikely adventure. They certainly offered no clues that explained how—or why—a Jewish couple from Philadelphia wound up in Nazi-controlled Vienna determined to rescue children whose lives were at stake.

Eleanor, however, had written it all down. At some point she typed out a richly detailed account of a seemingly far-fetched plan that began with a simple discussion between her husband, Gil, and his friend Louis Levine, the head of a national Jewish fraternal organization called Brith Sholom. At first glance, the typewritten pages read like an improbable, if not impossible, product of a vivid imagination.

Incredibly, the rescue mission took place precisely as Eleanor described it. In fact, its full historical significance extended well beyond her own account. The fifty boys and girls whose lives were saved by Gil and Eleanor Kraus comprised the largest single known group of children, traveling without their parents, who were legally admitted into the United States during the Holocaust.

I first learned of Eleanor’s private manuscript not long after Liz and I met in the summer of 2000. But it took another decade before I was able to give it my full attention and dig more deeply into this fascinating episode that for years had remained hidden in plain sight. It quickly became clear that this was much more than just another Holocaust rescue story. Research into Gil and Eleanor’s unheralded exploits led to a greater understanding of the obstacles that stood in their way as they valiantly (and in Gil’s case, single-mindedly) carried out their mission. The rescue project took place within the context of a profoundly hostile social and political environment in the United States that made their achievement all the more stunning—and, sadly, all the more singular. Moreover, the Krauses embarked on their journey during a brief window of time when the Nazis, determined to rid the Third Reich of all Jews, were allowing—in fact, pressuring—them to leave. Tragically, the greater challenge was finding countries that would take them in.

Gil and Eleanor Kraus never set out to be heroes. They were ordinary people who did something extraordinary and whose courageous deeds came very close to being lost to history. The stack of Eleanor’s pages, ever more fragile to the touch, has been carefully placed back in the desk drawer. At long last I am proud to bring the dramatic story of their quiet heroism out of the darkness.

No one in his right mind would go to Germany now. It’s not safe, especially for Jews. I’d be too scared to put a foot into that country, assuming the storm troopers would even let us in

.

—E

LEANOR

K

RAUS

P

HILADELPHIA

J

ANUARY

1939

E

leanor Kraus glanced around the dining room of her spacious three-story brick home on Cypress Street, in Philadelphia’s well-heeled Fitler Square neighborhood. The dinner hour was approaching, and Eleanor wanted to be sure that the table had been set properly. Although her husband, Gil, had not yet arrived home from his downtown law office, Eleanor had already dressed for the evening, choosing a silk dress and a pair of T-strap pumps. A double strand of pearls, set off against a new pair of matching earrings and a deep-red coat of lacquered nail polish, completed the look. Carlotta Greenfield, one of Gil’s nieces, was bringing her fiancé to dinner, and Eleanor, as always, wanted everything to shine.

When Gil walked through the front door a few minutes after six o’clock, Eleanor greeted him with a quick kiss on the cheek and reminded him that their guests were due to arrive any moment. Gil smiled knowingly at his wife, removed his overcoat, and set down his worn leather briefcase. As Eleanor was turning to dash back into the kitchen to check with the family cook on the dinner preparations, Gil caught her eye. “There is something that I need to discuss with you. Come into the bathroom while I shave. We can talk in there and while I’m getting dressed.”

Eleanor followed him upstairs and into the bathroom that adjoined the couple’s bedroom. Gil undid his necktie and pulled off his starched white dress shirt, leaving on a sleeveless undershirt as he prepared to shave. He was forty-two years old, and he and Eleanor had been married for more than fourteen years. But as he stood there in the bathroom, filling the sink with steaming hot water and then carefully scraping the straight edge razor across his face, it struck Eleanor just how fit and handsome he still was. With his broad shoulders and muscular torso, Gil had retained his physique of more than twenty years earlier, when he had competed on both the varsity wrestling and football teams during his undergraduate days at the University of Pennsylvania.

While Eleanor perched on the edge of the bathtub, Gil mentioned that his good friend Louis Levine had dropped by earlier that day. Levine was a successful real estate man in New York, but his visit to Gil’s office had nothing to do with business matters. He had come in his capacity as the grand master of Brith Sholom, a national Jewish fraternal organization to which Gil also belonged.

The two men had talked all that afternoon about a seemingly impossible idea—whether there might be a chance to help save Jewish children trapped inside Nazi Germany. Both Gil and Levine were only too aware of the worsening conditions for Jews living inside Hitler’s Reich, and they discussed the possibility that Brith Sholom might be able to sponsor some kind of rescue effort. Levine reminded Gil that the group had recently built a children’s summer camp along the banks of Perkiomen Creek in Collegeville, a semirural area about an hour outside of Philadelphia. On the other side of the camp, Brith Sholom had also constructed a large stone house that included twenty-five bedrooms. The house, intended for possible use as an old-age home, at the moment was standing completely empty.

Gil had enormous respect for Levine, and he listened closely as his friend spoke passionately about the ever-increasing dangers that were confronting Jews—adults and children alike—living in Nazi Germany. As the afternoon wore on, Levine finally got to the real point of his visit. He knew all about Gil’s reputation as a tough-minded lawyer who seemed able to solve just about any challenge put before him. Levine bluntly asked if Gil himself would be willing to take on the children’s rescue project.

Reacting almost instinctively, Gil surprised himself by immediately agreeing. Of course, he was aware of the difficult—perhaps insurmountable—obstacles that would stand in the way of such a project ever succeeding. Would the Nazis consider letting children leave Germany? And even if they would, America’s rigid immigration laws presented another imposing barrier. But Levine knew his friend well: Gil had a strong sense of justice, of right and wrong, and the rescue idea was right. Coincidentally three prominent Philadelphia Quakers—Rufus Jones, Robert Yarnall, and George Walton, all of whom Gil knew quite well—had traveled on their own to Berlin only a few weeks earlier in an effort to help Jews get out of Germany. Quaker groups in the United States, organized under the banner of the American Friends Service Committee, had become active in a variety of Jewish rescue efforts ever since Hitler had come to power in 1933. The Philadelphia trio had set out in hopes of meeting with high-ranking Nazi officials—perhaps even with Hitler himself—and arguing the case for making it easier for Jewish families to leave the Reich. But the high-minded mission was rebuffed. “Germans Ridicule Visiting Friends” read the headline in the December 9 edition of the Philadelphia

Evening Bulletin

. The accompanying article, an Associated Press dispatch from Berlin, reported that a German newspaper controlled by Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels “declared today that ‘we must laugh’ at the Quaker delegation, which is coming from the United States to investigate the condition of Jews and other minorities in Germany.”