(7/13) Affairs at Thrush Green (5 page)

Read (7/13) Affairs at Thrush Green Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #England, #Country life, #Pastoral Fiction, #Country Life - England

The two sat down at a table at the back of the empty room, and Rosa began to tell Gloria about the disco she had attended the night before when the door bell gave its mighty ping, and in came an elderly man. Rosa sighed.

'Here we go, then. I'll take him, dear. You do the next.'

She allowed the stranger to settle at a table near the window where he had a good view of the High Street, and had time to buff her nails on her apron while he studied the menu.

Slowly she approached.

'What can I get you?'

'Some coffee, please. Oh, and one of those iced buns.'

'White or black?'

The stranger look temporarily nonplussed.

'Surely you will bring me a pot of coffee and one of hot milk?'

it's usually just a cup.'

'Well, today will you please bring me a pot of each, as I have asked you.'

His eyes were very blue, Rosa noted, and flashed when he was cross. Proper old martinet, she reckoned. A general or admiral or something awkward like that, and used to having his own way, that was sure.

'It'll be extra,' she shrugged.

'I've no doubt I can stand the expense,' he said shortly. 'And I'm in a hurry, so look sharp.'

Rosa ambled into the kitchen at the rear.

'Got a right one in there,' she informed the kitchen staff. 'Wants a pot of coffee and one of hot milk. I ask you!'

She cast her eyes aloft as if seeking divine aid for such recalcitrance.

Old Mrs Jefferson, chief cook for many years at The Fuchsia Bush, and a staunch upholder of long-forgotten principles of service, gave one of her famous snorts.

'Then get what he's asked for. It ain't your place to query a customer's order. Do as you're told, and keep a civil tongue in your head.'

'You don't have to face the customers,' grumbled Rosa.

'I have in my time,' reminded Mrs Jefferson, 'and given satisfaction too, my girl, which is a lot more than anyone can say about you. Now, get your tray ready, and see if you can manage a smile on that ugly mug of yours. Enough to turn the milk sour looking like that.'

She whisked back and forth from stove to the central table, nimble as ever despite her impressive bulk.

Rosa took the tray without a word, but if looks could have killed, Mrs Jefferson would have been a substantial corpse on the kitchen floor.

***

Half an hour or so later, the stranger emerged from The Fuchsia Bush into the muggy air of Lulling High Street.

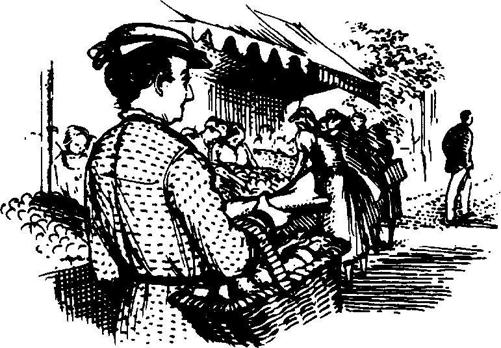

The shoppers were in action now, and the tall figure had to circumvent perambulators, dogs on leads, and worst of all, two ladies having a lengthy gossip with their baskets on wheels spread behind them across the width of the pavement.

'Excuse me!' said the man firmly, pushing aside one of the baskets with a well-polished brogue.

'Really!' exclaimed one of the ladies. 'What are people coming to? It's a pity if we can't stop to say a civil word to our friends!'

But she waited until the stranger was out of earshot, before making these protestations.

Her companion was gazing after the upright figure making his way up the slight incline towards the market place.

'I believe I've seen him before,' she mused. 'Years ago.'

'Well, I shouldn't bother to resume the acquaintanceship,' replied her friend. 'A very thrusting sort of individual, I should think.'

They settled back into their former positions and continued their interrupted discussion.

Miss Violet Lovelock was in the market place comparing the price of leeks on each of the vegetable stalls.

It was really outrageous how expensive even the lowliest vegetables were these days, she thought. Perhaps three of Dawson's thick leeks would make enough soup for two meals for the three of them. Plenty of the leek water, of course, and some salt and pepper should eke things out.

She was just putting her parcel in her basket, and endeavouring to avert her eyes from page three of the newspaper in which the leeks were wrapped—what was the world coming to!—when she noticed the figure striding vigorously uphill across the road.

Miss Violet gazed with concentration. She knew that walk. Who was he? If only her sight were keener, but she feared that her sisters were quite right in urging her to get her spectacles changed. Now a lorry was in the way. Now he had stopped to look in Barlow's window, and had his back to her. If only she could place him! There was something familiar about that straight back. Now who could it be?

The figure moved on, and suddenly opened the door of the solicitors, Twitter and Venables. In a trice he had vanished into the murk of that establishment, leaving Miss Violet to ruminate on her way home.

Perhaps she had been mistaken. Perhaps it was a complete stranger going into dear Justin Venables' office on business.

Her sight really was getting worse, and it made it quite easy to make mistakes when people were at a distance. She would think no more about it.

And yet—there was

something

! And that something had given her a thrill of pleasure, as though some long-forgotten happiness had been stirred into life again, on that quiet grey morning in the damp Lulling street.

4. Rumours At Thrush Green

MARCH ARRIVED, but there was nothing lion-like about its coming.

The same grey stillness enveloped Lulling and Thrush Green. The same listlessness enveloped the inhabitants. Everyone longed for the clouds to lift, for a great wind to rush gustily through the trees, for the streets to be blown dry and for spirits to feel exhilaration again.

At Lulling vicarage Charles was having a most uncomfortable interview with one of his keenest parishioners. Mrs Thurgood was the widow of a wealthy provision merchant who had supplied a great many first-class Cotswold grocers with such exotic articles as coffee beans, tea, spices, dried fruits and preserved fruits, jars of ginger, toothsome pâtés and a host of other elegant comestibles.

His fleet of dark blue vans, chastely inscribed in gold lettering, were a common sight in the district, and Mrs Thurgood, carrying on the tradition of her husband, was a generous donor to all the church finances, and boasted that she never missed a service.

Anthony Bull had been her idea of the perfect vicar. 'The sort of fellow,' she had been heard to say, 'that one can invite quite safely to the house, no matter who is staying.' She approved of his distinguished looks, his charm of manner and the content of his sermons. She liked the ritual, the robes, the genuflecting, the sonorous chanting, the plethora of descants and the use of the seven-fold Amen. He was, in her eyes, completely satisfactory, and she mourned his promotion to a Kensington living.

She was also making it quite clear that she found Charles Henstock much inferior in every way to his predecessor.

'I can't believe,' she was telling Charles, 'that dear Mr Bull didn't mention this business of new kneelers for the Lady Chapel.'

'He had a great deal to think of, you know,' said Charles, 'before his move. It probably slipped his memory.'

'I doubt it,' replied Mrs Thurgood. 'I spoke to him a few weeks before his departure pointing out the need for a complete new set. He said, I remember, that he would mention it to you, as obviously you would be in charge when the work was undertaken.'

And who could blame Anthony Bull for shelving the problem, thought the rector? But now, it seemed, the birds had come home to roost, and it had become his problem.

'Do we really need new kneelers?' began Charles. 'The present ones seem very attractive, and I fear that we must guard against undue expense.'

'Of course

we need them! And I made it quite clear to Mr Bull from the outset, that I would be happy to pay for all the materials. It's just a case of getting the Mothers' Union, and the Ladies' Guild, and the Church Flower Ladies to take on the work—one kneeler apiece should be all that is needed—and to get your permission to go ahead.'

At the mention of all the potential kneeler-makers, many of whom Charles found profoundly intimidating, he found his mind turning to the hosts of Midian who prowled and prowled around.

'And, of course,' went on his formidable visitor, 'it would be best to have one person leading the way.'

Like a bull-dozer, thought Charles unhappily.

'To co-ordinate the whole scheme,' said Mrs Thurgood. 'For one thing we must think about Design and Colour.'

'But surely, each lady would choose her own pattern?'

'Good gracious, no! Naturally the main colour must be blue. Soft furnishings in Lady Chapels are traditionally blue. And one must have the kneelers of uniform size. And frankly, I think that they should all be of the same design. Luckily, my daughter Janet, who is exceptionally gifted and has studied Design, Tapestry Work and Embroidery at Art School, has drawn up a charming pattern on squared paper, ready for the project.'

Charles began to feel besieged. The preliminary skirmishes were over. Now the heavy guns were in action.

He looked out at the misty garden, the beaded grass and the cedar tree, darker than ever with moisture. That glimpse of placid unchanging nature gave him the strength to counter-attack.

'It's plain that you have given much thought to the matter,' said Charles kindly. 'And it is most generous of you to offer to face the expense. I shall talk to Dimity about it—she is always so practical—and have a word with my church-wardens. Perhaps I may ring you in a day or two?'

Even the redoubtable Mrs Thurgood realized that she had advanced as far as was possible on the present occasion. Now was the moment to halt and remuster her strength for future assaults.

'Very well,' she agreed, rising from the vicarage sofa. 'Everything is absolutely ready as soon as you give the word. I know,' she added meaningly, as she preceded the vicar of Lulling into the hall, 'that it was a matter very dear to Mr Bull's heart. How we miss him!'

This parting thrust was successfully parried by the genuine sweetness of Charles's smile.

'We do indeed, Mrs Thurgood,' he said. 'But Lulling's loss was Kensington's gain, and I hear he is exceptionally happy in his new parish.'

He watched Mrs Thurgood's ramrod-straight back departing down the drive, and sighed.

The Mothers' Union! The Ladies' Guild! The Church Flower Ladies!

Could he ever hope to gain a victory against such a monstrous regiment of women?

It was Ella Bembridge, Dotty's old friend, who first discovered the identity of the tall stranger in Lulling. Like so many ladies who live alone, Ella had the uncommon knack of assimilating local gossip and, what was even better, of remembering it. It was not that she actively ferreted out information as many of the Thrush Green and Lulling ladies were wont to do. Such obvious seekers after gossip were well-known in the community, and those who met them were on their guard and curbed their tongues.

But Ella was invariably engaged in one of her many crafts, clacking her handloom, knitting or crocheting at incredible speed, or simply rolling one of her deplorable cigarettes, and so appeared to the retailer of local news to be attending principally to the matter in hand. Consequently, much was divulged, and Ella's keen mind retained it.

'Did you know that the Venables have got a visitor?' she asked Charles and Dimity when she called in for the parish magazine one morning.

'Anyone we know?' asked Dimity.

'I shouldn't think so. He's been overseas most of his life, but he was born and brought up here, and went to the grammar school when Dotty's father was headmaster.'

'Poor boy!' exclaimed Dimity. Mr Harmer's idea of corporal punishment would have brought him before any present day court on a charge of battery and assault, if not grievous bodily harm, and the tales of elderly old boys, even though understandably exaggerated, were enough to curdle the blood.

'Kit Armitage. That's his name,' went on Ella, stuffing the parish magazine between a head of celery and her library book in the rather lop-sided basket of her own making, i expect Dotty will remember him, and the Lovelocks, of course, but before our time here.'

'Is he staying long?'

'I don't think so. He's looking for a small place of his own now that he's retired. Justin's always dealt with the family's legal affairs, and they've kept in touch over the years, and I gather he's just having a week or so with them until he gets settled.'