Read 97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement Online

Authors: Jane Ziegelman

Tags: #General, #Cooking, #19th Century, #History: American, #United States - State & Local - General, #United States - 19th Century, #Social History, #Lower East Side (New York, #Emigration & Immigration, #Social Science, #Nutrition, #New York - Local History, #New York, #N.Y.), #State & Local, #Agriculture & Food, #Food habits, #Immigrants, #United States, #Middle Atlantic, #History, #History - U.S., #United States - State & Local - Middle Atlantic, #New York (State)

97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement (21 page)

In the mid-1930s, the

Daily Forward

, the East Side’s leading Yiddish newspaper, began a regular cooking feature edited by Regina Frishwasser. The recipes that appeared in the column were sent in by readers—home cooks with limited time and limited budgets as well. In the 1940s, Frishwasser collected the recipes into

Jewish American Cook Book

. The purpose of the book, she writes in her preface, “is not to bring glamour to a menu, but rather to bring our foods in the easiest way possible to those who want them.” Here is her recipe for a

krupnik

that used dried mushrooms, barley, lima beans, and yellow split peas.

K

RUPNIK

Bring 2 quarts water to a boil, and add 1 cup yellow split peas, ½ cup minute barley, ½ cup lima beans, and 1 teaspoon salt. Simmer 1 hour and add 1 ounce broken dried mushrooms, 1 minced onion, 1 diced carrot, and 1 diced parsley [root]. Cook until the vegetables are tender. Fry 1 minced onion in 2 tablespoons butter until golden brown, then add to the soup.

8

Come summer, Jewish cooks turned to chilled soups, like meatless borscht served with sour cream and boiled egg, just one of the many mouth-puckering foods consumed by the immigrants, a taste preference they had acquired on the other side of the ocean. Back in Europe, the traditional souring agent in borscht was home-fermented beet juice otherwise known as

rossel

. Once in America, cooks turned to a store-bought product called sour salt (tartaric acid) to give their borscht the required zing. Like lemonade, it was the sourness of borscht that made it so refreshing. Schav was another cold and sour soup that the Jews consumed as a summer tonic. Murky green in color, it was made from boiled and chopped sorrel leaves, a plant loaded with vitamin C. The appearance of sorrel on the East Side pushcarts signaled that spring had come to the ghetto. Tenement housewives prepared their first batch of schav sometime in mid-May, and served it “the old Ghetto way,” with sour cream, bits of chopped egg, cucumber, and scallion, so it was part soup and part salad. Schav was also popular in the East Side cafés, where customers sipped it from a glass like iced tea.

In warm weather, as pushcarts filled with summer vegetables, the Jews became avid salad-eaters, though not the leafy green kind favored by the Italians that we are most familiar with today. Instead, they chopped cucumber, radish, scallion, and pepper into bite-size chunks and sprinkled them with a little salt and pepper. In a more luxurious version, the raw vegetables were crowned with a scoop of cottage cheese or sour cream, a dish once referred to as “farmer’s chop suey.” This classic Jewish creation was reportedly the food that Harry Houdini (a Hungarian-born Jew) requested on his deathbed.

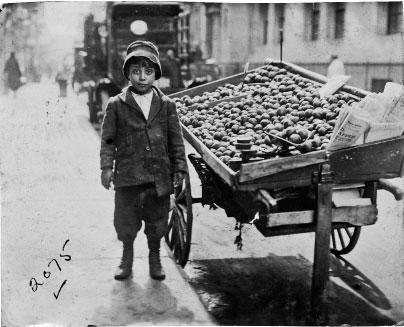

When the first pushcart survey was taken in 1905, fruit peddlers held sway over the market, occupying more curb space than vendors of any other food. On the far side of the ocean, Jewish fruit consumption was more or less limited to whatever grew locally, including apples, peaches, cherries, berries, and, above all, plums, which grew on the outskirts of the shtetls and which Jewish cooks made into a thick, dark preserve called

pavel

, a kind of plum butter. Plums were also dried along with apples and used in cooking. Jewish cooks added prunes to festive dishes like tzimmes (sweet glazed carrots) and cholent, or used it as a filling for hamantaschen, the triangle-shaped Purim cookie. When crushed and left to ferment, plums were the foundation for slivovitz, a kind of Eastern European firewater. At the pushcart market, immigrant Jews discovered an Eden of melons, citrus, stone fruits, and tropical wonderments like pineapple, banana, and even coconut, which the vendor sold, pre-cracked, the white oily shards floating in jars of cloudy water. In fact, many kinds of fruits—melons, pineapple, even oranges—were sold presliced and hawked as street food, a practice that city officials frowned on. (According to the New York sanitary police, the consumption of bad fruit purchased from street peddlers was a leading cause of death among East Side children.) Where other vendors packed up by dinnertime, the fruit vendors remained on the street long after the sun went down, their carts illuminated by flaming torches. Fathers coming home from work would stop by the fruit peddler for penny apples to give to the kids. On summer nights, when tenement-dwellers poured into the streets for a breath of fresh air, strolling East Siders paused at the fruit carts for a cool slice of watermelon. Fruit was the great affordable luxury of the tenement Jews.

Family members often took turns at the pushcart. Children peddled in the afternoon when school let out.

CSS Photography Archives, Courtesy of Community Service Society of New York and the Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University

In the early 1920s, a Boston dietician named Bertha Wood conducted a multiethnic study of immigrant eating habits, eventually published as a book,

Foods of the Foreign-Born in Relation to Health

. As the title suggests, the book was written for health-care professionals—visiting nurses, settlement workers, and dispensary doctors—who served the immigrant community. Though well versed in current medical practice, they knew very little about the immigrants’ foodways, a tremendous handicap in treating the immigrant patient. For each group in her study, Wood identified the leading food deficiencies and most harmful tendencies. She was also ready, however, to point out where the immigrant cook was superior to her native-born counterpart.

At less than a hundred pages,

Foods of the Foreign-Born

is a curious little book. Ms. Wood approaches her immigrant subjects with a degree of culinary open-mindedness unusual for the 1920s, a particularly anxious period in American political history. At the same time, she is firmly moored in the food wisdom of her day, with a deep faith in the value of bland, unadorned cooking like creamed soups and boiled vegetables. Her 1920s perspective helps explain Wood’s two most persistent concerns with the immigrant kitchen: too much seasoning and too little milk. Ms. Wood declared the Jews guilty of both preparing highly seasoned foods (one reason the Jews were so nervous) and depriving their children of sufficient milk, “nature’s most perfect food.”

Red Cross workers distributing milk, “nature’s most perfect food,” to newly landed immigrants.

Library of Congress

Among the foods that Ms. Wood objected to most was a much-loved Jewish staple: the pickle. “Perhaps no other people,” Wood observed, “have so many ‘sours’ as the Jews. In the Jewish sections of our large cities,” she continued,

There are storekeepers whose only goods are pickles. They have cabbages pickled whole, shredded, or chopped and rolled in leaves; peppers pickled; also string beans; cucumbers, sour, half sour, and salted; beets; and many kinds of meat and fish. This excessive use of pickled foods destroys the taste for milder flavors, causes irritation, and renders assimilation more difficult.

9

More alarming still was the pickle habit among Jewish school kids, who spent their lunch money on pickles and nothing else, their appetites ruined for more appropriate foods like milk and crackers. The taste of the standard Jewish pickle was so aggressive—briny, garlicky, sour—and so foreign to the native palate that Americans like Ms. Wood wondered how anyone, children especially, could eat them by choice. Instead, they saw pickle-eating as a kind of compulsion. The undernourished child was drawn to pickles the same way an adult was drawn to alcohol. More than a food, the pickle was a kind of drug for tenement children, who were still too young for whiskey.

At the pushcart market, the pickle stand was a rendezvous for shoppers. Here, standing among the barrels, hungry East Siders could buy a single pickle and eat it on the spot, then continue with their errands. Pickles were also sold in bulk, dished from the barrel with a sieve and packed into jars supplied by the shopper. Uptown visitors to the market were shocked by the size of Jewish pickles, some “large enough to kill a baby.” These overgrown sours were cut into thick rounds that sold for a penny a piece and placed between bread to make a pickle sandwich, a typical East Side lunch.

The following recipe is adapted from Jennie Grossinger’s

The Art of Jewish Cooking

:

D

ILL

P

ICKLES

30 Kirby cucumbers of roughly the same size

½ cup kosher salt

2 quarts water

2 tablespoons white vinegar

4 cloves garlic

1 dried red pepper

¼ teaspoon mustard seed

2 coin-sized slices fresh horseradish

1 teaspoon mixed pickling spice

20 sprigs of dill

Wash and dry cucumbers and arrange them in a large jar or two smaller jars, alternating a layer of cucumbers with a layer of dill. Combine salt and water and bring to boil. Turn off heat. Add vinegar and spices and pour liquid over cucumbers. They should be immersed. If necessary, add more saltwater. Cover and keep in a cool place for 1 week. If you like green pickles, Mrs. Grossinger recommends you try one after 5 days.

10

Though pushcarts formed the backbone of the immigrant food economy, East Siders also patronized neighborhood shops: butchers, groceries, delicatessens, and dairy stores. This last group, a type of business that no longer exists, included Breakstone & Levine, sellers of milk, butter, and cheese, formerly located on Cherry Street, and forerunner to the modern-day Breakstone brand. But inside the tenements, hidden from the casual observer, immigrants trafficked in a shadow food economy in which neighbors took responsibility for feeding each other. Transactions within the tenement were most often cashless. Neighbors exchanged gifts of food as part of an improvised bartering system in which the poor gave to the truly destitute, or, in many cases, to families struck by tragedy: a death, sickness, a lost job. In return for her edible gifts, the tenement homemaker received the same consideration whenever her luck was down—and no one in the tenements was immune from a run of bad luck. Mrs. Rogarshevsky, a widow with six kids, was certainly eligible, and edible charity must have streamed into the apartment during and after her husband’s long illness, when she adjusted to her new role as breadwinner.

The continuous give-and-take that carried food from one apartment to another was a strategy for survival among tenement-dwellers sustained by the tenement itself. In buildings where apartment doors were hardly ever locked or even closed, where stairways were used as vertical playgrounds, rooftops functioned as communal bedrooms, and front stoops were open-air living rooms, the business of daily life was an essentially shared experience. Tenement walls, thin to begin with, were riddled with windows, windows between rooms, between apartments, and windows that opened onto the hallway. As a result, sounds easily leaked out of one living space and into another. Or, if they were loud enough, ricocheted through the central stairwell. During summer, when East Siders hungered for fresh air, and windows to the outside world were open wide, voices were broadcast through the building via the airshaft. In the brownstones and apartment houses above 14th Street, New Yorkers lived more discreetly, sealed off from the larger world in their own domestic sanctuary. In the tenements, the people who lived above and below you were often blood relatives, but even if they weren’t, you were fully briefed on their domestic status down to the most intimate details, and vice versa.