A Companion to the History of the Book (10 page)

Read A Companion to the History of the Book Online

Authors: Simon Eliot,Jonathan Rose

However, if your time series shows fluctuations then other methods may be necessary to distinguish between different influences. Monthly figures for tonnage of paper can show the long-term

trend

in paper production. In addition, there may be

regular fluctuations

which indicate a seasonal variation. Lastly, there may be

irregular fluctuations

, such as the fall in paper production during civil war, or changes in tariffs and taxes. The book historian has to decide what the factors might be, then use the tool of time-series analysis to estimate the effect of short-term influences on the long-term trends. Another way of isolating trends from regular fluctuations is to plot four- or five-year moving averages, as Simon Eliot does to considerable effect in his essential source (Eliot 1994)

.

However, it can have its limitations: if you do not know the frequency of the fluctuations, you can misrepresent the data by selecting the wrong length of time. (In my work on book-production costs, time-series data are affected by business cycles, which in the nineteenth century varied in length from five to ten years.)

To isolate the variations, you calculate the original data as a percentage of the trend, and then the deviation from the original data as a percentage of the trend. This result conflates regular cycles with irregular fluctuations which can make interpretation difficult; for example, showing seasonal variations in the cost of paper, the overall trend in the cost and the irregular variations caused by supply problems during blockades, wars, transport problems, and so on. You can isolate the regular cycles from the irregular fluctuations to separate the long-run trend, recurrent seasonal fluctuations, and residual fluctuations so that you can analyze each separately. Feinstein and Thomas give a clear account of how this is calculated on data on bankruptcies in England from 1780 to 1784 (2002: 28–30). O f course, this has to be used appropriately: applied to the STCs, the regular cycles of five and ten years may tell us more about cataloguers’ habits of “rou nding” the d ate of publication to the next half-decade, decade, or century than giving us insights into cycles of production. In this case, the seasonal and irregular fluctuations caused by other factors may be of more significance. In the end, the mode of presentation is the choice of the book historian who is, after all, simply offering an interpretation of the statistics.

Reading Variables

Many questions book historians want to ask are about the relationship between different factors. We want to know if there is a relationship, how strong it is, and, if possible, what form it takes and whether it is coincidental. I might be interested to know, for instance, if there is a relationship between the quantity of books manufactured and the average price, or perhaps the number of books written by an author and his or her wealth at death. As a comparison between two numerical variables, the task is largely a statistical one. However, when qualitative responses are coded for statistical analysis, some level of interpretation becomes integrated into the data. Social scientists familiar with the design of questionnaires have strict methodological procedures to reduce researcher bias and numerous statistical methods to interpret combinations of numerical and category variables.

Researchers in this field have employed techniques found in studies of contemporary society from questionnaires to content analysis of the media. One powerful tool is multivariate analysis, which is commonly used by media and marketing analysts today and requires large, robust datasets or survey data. Eiri Elvestad and Arild Blekesaune use data about newspaper-reading in twenty-two European countries from the European Social Survey (2002), demographic data from Eurostat, and data from World Press Trends 2005. T heir multivariate analysis is used to describe national differences in newspaper-reading and to explain how these differences occur (Elvestad and Blekesaune 2006). Vincent Greaney (1980), on the other hand, uses data from a survey to explore the factors related to amount and type of leisure-time reading. Among the variables he examined were gender, level of reading attainment, leisure activities, socio-economic status, family size, choice of television programs, and location and type of primary school attended. Not all had a significant influence on the 5.4 percent of leisure time the pupils devoted to recreational reading. Using multiple regression analyses, Greaney deduced that “most of the explained variation (22.9 per cent) in time devoted to books was accounted for by a combination of the variables gender, reading attainment, school location, library membership, and birth order” (1980: 337). To improve our understanding of the book and its effect on society through history, it is important to adapt and extend these kinds of analysis so that we can use them on the historical record.

One project that seeks to record elusive information on changes in reading habits is the Reading Experience Database (RED). The project has a web-based public interface for researchers, who can input data to the project wherever they are connected. The online form prompts the researcher to input the details of who read what, where and when, in company or alone, silently or aloud. As the historical period is wide – from 1450 to 1945 – standard sociological groupings are not useful and categories have been designed for the purpose. The genre groupings are also specially designed to capture popular subjects through the period. Information is drawn from a range of sources, including autobiographies, diaries, letters, scrapbooks, and annotations in books, and thus obviously cannot be considered a random sample of historical reading practices. The sample is selective, representing as it does those who had the leisure and inclination to record their reading experience. It will also be biased by the sources read by the contributors – inevitably “rich” sources are preferred. Even within this group, however, it would be interesting to compare variables: what proportion of Bible readers in the first half of the sixteenth century read aloud to company? How did this change in the following centuries? What did agricultural laborers read at the time of the French Revolution and how had this changed by the fall of Napoleon Bonaparte?

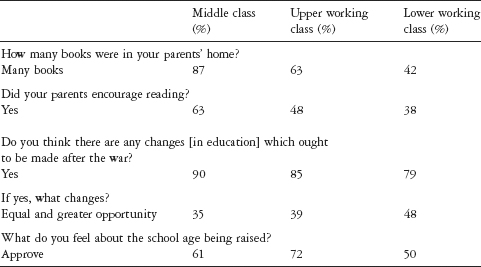

The RED form was designed to investigate historical reading practice. But often historians have to use surveys or questionnaires created in the past. Researchers interested in mid-twentieth-century reading habits and library use in Britain have turned to the Mass Observation archive. Helpfully, interview subjects were coded according to sex, age group, class, and sometimes location, and the survey used standard sociological groupings. The numbers of respondents are known and this makes it far easier to analyze the findings and quantify the correlation. Joseph McAleer (1992), Alistair Black (2000), and Jonathan Rose (2001), amongst others, have made use of this valuable source of qualitative and quantitative information for the history of the book. Rose’s investigation of the

Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes

(2001) quotes figures from a survey in 1944 which asked: “How many books were in your parents’ home? And did your parents encourage reading?” The survey found “that nearly two-thirds of skilled workers and almost half of all unskilled workers grew up in homes with substantial collections of books and that working class parents of the previous generation had encouraged reading” (Rose 2001: 231). In this case, it may not be necessary to look for a statistical correlation between the factors; the link seems obvious. However, it might also be useful to calculate a correlation between the following question: “Do you think there are any changes in the way education is run which ought to be made after the war?” and the suggested changes (“Equal and greater opportunity” and “What do you feel about the school leaving age being raised?”). Of the two suggested changes, the stronger correlation turns out to be between low socio-economic class and the desire for equal and greater opportunity which supports the interpretation that this is the most desired change. Raising the school leaving age is not the reason as the correlation is low (at 0.54; see

table 3.2

).

There is a body of work on the phenomenon of book groups, which traces their history and resurgent popularity. Scholars in this field have used survey methods in their research. Elizabeth Long’s (2003) ethnographic study takes an historical view of women’s book groups from the Civil War in America to the present day, using questionnaires and observer-participation techniques to gather data from currently active groups. Jenny Hartley’s (2001) survey of contemporary British book groups draws on a core of 350 groups which answered questionnaires designed to elicit qualitative information, which Hartley then followed up with e-mails and visits. Exploring their composition and processes, she presents the voices and attitudes of the various groups, supporting her commentary with an indication of their representativeness derived from a numerical analysis of the responses. Using the powerful reach of the Internet, DeNel Sedo’s (2003) online survey of book clubs lends itself to statistical analysis of location, composition, age, genre preference, and so on. The self-selected sample supports Long’s and Hartley’s evidence that book groups appeal predominantly to women and are used largely as a place to reflect upon their life experience. Sedo compares members’ views of the advantages and disadvantages of meeting as a group at a fixed time and place with the less constrained social interaction available online.

Table 3.2

Correlating responses to questions asked in 1944 survey

Source

: Rose (2001: tables 5.10 and 6.5A)

The Internet has been beneficial to many projects. Finding aids, census information, data sets, and a lot more besides are directly accessible. Creating a digital archive which can then be made available via the Internet is

de rigueur

for a new research project today. The Internet has made the tracking of books and dissemination of texts much easier for professionals and amateur enthusiasts alike. Information scientists analyze the information recorded about a book or article on a database or in a citation index such as the ISI Web of Knowledge

SM

(

www.thomsonisi.com

), Scientific Citation Index, Arts and Humanities Index, and so on. Applied to scientific publications, it is a way of determining the life-cycle of the literature on a specific subject. The analysis of the number of citations – in particular, their distribution and longevity – can be used to quantify “reputation,” and this has been used to inform policy on scientific research and as an indicator of the spread of ideas and research findings. At the opposite end of the spectrum, a community site, bookcrossing.com, enables enthusiasts to track the life of a book as it passes though the hands of readers. Both measure the dissemination and usage of the printed text, but for very different purposes.

Geographical Distribution

Globalization, visionaries proclaim, changes our understanding of time and space, and this is perhaps particularly true in the case of the application of Geographical Information Software (GIS). Early studies of book distribution in Canada traced the westward spread of communication routes though the building of roads and railways and the rise of newsagent networks. Harold Innis and others working in the 1950s and 1960s showed the importance of geography in our conceptualization of the historical spread of print (Innis 1950, 1951; Carpenter and McLuhan 1960). However, the logistics of collating and plotting geographical data by hand meant that spatial analysis of historical data was limited. Now GIS can offer the opportunity of storing, mapping, and interrogating spatial data on an unprecedented scale. This has given rise to a number of fascinating historical atlases which show graphically, for instance, examples of agricultural land use, urbanization, or the transport infrastructure in the past. The correlation of spatial and temporal data gives insights into such things as the rise and decline of centers of print production within a country. Data from other historical sources can be included as variables within the analysis of print culture and help to confirm old theories (such as the links between the stage coach and sea routes and the spread of print distribution) and raise new and now potentially answerable questions such as “Do the demographics of printers and religious sects correlate?”

While the potential of GIS is considerable, two obstacles have slowed down its adoption in book history. First, the task of collating and combining databases to ensure the information is in a suitable form for analysis is a big one, particularly when many databases were originally constructed without reference to the needs of GIS software. Secondly, GIS software is better at exploring data spatially at a specific historical moment than tracking developments through time. Ian Gregory points out how it has been used effectively in historical research and then points to its limitations:

A good example of this approach is taken by Kennedy

et al.

(1999) in their atlas of the Great Irish famine. The atlas uses census data to show demographic changes resulting from the famine. At its core are layers representing the different administrative geographies used to publish the censuses of 1841, 1851, 1861 and 1871. These layers are linked to a wide variety of census data from these dates. This allows sequences of maps to be produced showing, for example, how the spatial distribution of housing conditions and use of the Irish language change over time.