A Companion to the History of the Book (13 page)

Read A Companion to the History of the Book Online

Authors: Simon Eliot,Jonathan Rose

This conclusion indicates that historians of reading need to be particularly sensitive to the biographical determinants of class, gender, and geographical location that helped to shape the individual’s reading life. But it also suggests that in order to test theories, such as the “reading revolution” hypothesis, we need to compile as many case studies as possible. The Reading Experience Database, launched by the Open University and the British Library in the late 1990s, is designed to bring such case studies together in order to help determine how readers of earlier periods approached their books. As the various case studies referred to in this chapter reveal, the reading experience since 1750 cannot be described as uniform or monolithic. However, by bringing together enough of these case studies, it should be possible to replace the opposed terms “intensive” and “extensive” with a more nuanced account of the various practices available to readers in the eighteenth century. This is, in part, a question of deciding which kind of history we want. The broad, epochal sweep favored by those historians who contrast manuscript with print, or intensive with extensive, is important, but such models may, of necessity, neglect or ignore those individuals or groups who appear to be “atypical.” These individual or local practices are important because they help us to recognize that many different forms of reading were taking place at a given historical moment. For example, in the same period that the middle-class Joseph Hunter was beginning to read extensively, many working-class readers still had access to only a very limited number of texts (Vincent 1983).

If reading extensively was increasingly the norm for middle-class readers during the early nineteenth century, what evidence do we have for those lower down the social scale? As Martyn Lyons has noted, “the lower-middle classes, aspiring artisans and white-collar workers” were amongst those who “swelled the clientele of lending libraries” throughout Europe during the Victorian period, but records of their borrowings tell us little about the way in which they actually read (Lyons 1999). By the 1870s, two-thirds of the British working class could read, but most studies of working-class reading are reliant upon the autobiographical writings of a small but eloquent artisan elite (Vincent 1982). When narrating the story of their life, members of this group “ra rely failed to give a description of their reading, and many of them outlined the detailed reading programmes which had guided and improved them” (Lyons 1999: 331–2). For example, the Chartist poet and lecturer Thomas Cooper recalled how he had attempted to master several languages and memorize “the entire Paradise Lost, and 7 of the best plays of Shakespeare” by reading in the early hours of the morning before going to work (Lyons 1999: 337). Such texts confirm the importance of reading to the ideology of self-improvement and they demonstrate just how much ef fort some working-class readers were prepared to put into becoming well read.

As Kate Flint has noted, however, it is important to “exercise a certain amount of caution when using autobiographical material.” All autobiography is a form of self-fashioning and involves the selection and arrangement of events (Flint 1993: 187). This is, of course, also true of other sources, such as letters and diaries, which involve the framing of events, but autobiography shares many of the literary techniques associated with fiction. Each author had different reasons for wishing to foreground the importance of reading in his or her intellectual or emotional development, but they often used established tropes or motifs to write about this experience. One such trope often found in working-class writing is the undertaking (or failure) of a detailed “programme of reading,” such as that referred to by Cooper. Many working-class writers also describe an epiphanic moment in which they encountered a text that transformed their life. Flint notes that a scene of childhood reading becomes a recurrent motif in female autobiography where it is often used to reflect upon freedoms lost after marriage (Flint 1993: 208).

However, despite these limitations, autobiography provides vital information about the new readers of the nineteenth century. As Flint’s work suggests, the recollection of adolescence provides a substantial body of evidence about the control exercised over young female readers during this period, as well as an important insight into the ways in which women surreptitiously acquired and enjoyed forbidden texts (Flint 1993: 209). Similarly, working-class autobiography provides evidence of the rules governing reading within specific families or communities. For example, in an autobiographical essay drafted shortly after he became famous as “the Northamptonshire Peasant Poet” in 1820, John Clare recalled how his skills in reading and writing made him different from his parents: “Both my parents was illiterate to the last degree. My mother knew not a single letter ? my father could read a little in the bible or testament and was very fond of the supersti[ti]ous tales that are hawked about a sheet for a penny” (Clare 1996: 2).

Clare uses the term “illiterate” here to refer to writing rather than reading, and it is clear that he was the only member of his family that could both read and write. Households in which various levels of literacy operated were common amongst working-class communities during this period, and it is important to note that the inability to read did not necessarily prevent people who were as “illiterate” as Clare’s mother from participating in print culture. Both Clare and his father frequently read aloud and this form of text transmission remained important amongst groups where different levels of literacy coexisted well into the twentieth century. Clare also reveals that he began to hide his own fondness for “reading and scribbling” from his parents when it became apparent that he was not using these skills to acquire a better-paid job, and he makes several other references to concealing his reading from the rest of his community. His autobiography and others like it thus help to reveal the complex nature of working-class attitudes toward literacy and culture. A close study of these texts will allow historians of reading to avoid what Roger Chartier has described as a naïve identification of “the people” with the oral transmission of texts (Chartier 1994: 22). Clare’s solitary, hidden reading is an important part of the history of working-class reading, but it would be equally naïve to assume that he is a typical working-class reader.

In order to understand better the activity of reading, book historians have begun to explore a wide range of sources, including representations in literary and pictorial texts, and the new physical forms taken by texts as they are reproduced. As Chartier has noted, such sources are of limited use because reading “cannot be deduced from the texts it makes use of,” but he also argues that the reader is never entirely free to make meaning. Readers “obey rules, follow logical systems, imitate models” (Chartier 1994: 22–3). The best way in which to rediscover the systems that underpinned past reading practices is to explore the kinds of autobiographical materials that have been the subject of this chapter.

References and Further Reading

Baggerman, Arianne (1997) “The Cultural Universe of a Dutch Child.”

Eighteenth Century Studies

, 31 (1): 129–34.

Beal, Peter (1993) “Notions in Garrison: The Seventeenth-century Commonplace Book.” In W. Speed Hill (ed.),

New Ways of Looking at Old Texts

, pp. 131–47. New York: RETS.

Beetham, Margaret (2000) “In Search of the Historical Reader.”

Siegener Periodicum zur internationalen empirischen Literaturwissenschaft

[

SPIEL

], 19 : 8 9 –104.

Brewer, John (1996) “Reconstructing the Reader: Prescriptions, Texts and Strategies in Anna Lar-pent’s Reading.” In James Raven et al. (eds.),

The Practice and Representation of Reading in England

, pp. 226–45. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chartier, Roger (1994)

The Order of Books.

Cambridge: Polity.

Clanchy, M. T. (1993)

From Memory to Written Record: England 1066–1307

, 2nd edn. Oxford: Blackwell.

Clare, John (1996)

John Clare by Himself

, ed. Eric Robinson and David Powell. Ashington and Manchester: MidNag and Carcanet.

Colclough, Stephen (1998) “Recovering the Reader: Commonplace Books and Diaries as Sources of Reading Experience.”

Publishing History,

44: 5–37.

— (2000) “Procuring Books and Consuming Texts : The Reading Experience of a Sheffield Apprentice, 1798.”

Book History

, 3: 21–44.

— (2004) “ ‘R R, A Remarkable Thing or Action’: John Dawson as Reader and Annotator.”

Variants,

2/3: 61–78.

Darnton, Robert (1984)

The Great Cat Massacre

. London: Allen Lane.

— (1990)

The Kiss of Lamourette : Reflections in Cultural History

. New York: Norton.

— (2000) “Extraordinary Commonplaces.”

New York Review of Books

, December 21: 82–7.

Engelsing, Rolf (1974)

Der Burger als Leser: Leserge-schichte in Deutschland 1500–1800

. Stuttgart: Metzler.

Flint, Kate (1993)

The Woman Reader 1837–1914.

Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Grafton, Anthony (1997) “Is the History of Reading a Marginal Enterprise? Guillaume Bude and his Books.”

Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America

, 91: 139–57.

Hall, David (1996) “The Uses of Literacy in New England, 1600–1850.” In David Hall (ed.),

Cultures of Print: Essays in the History of the Book

, pp. 36–76. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Jackson, H. J. (2001)

Marginalia: Readers Writing in Books

. London: Yale University Press.

Jardine, Lisa and Grafton, Anthony (1990) “ ‘Studied for Action’: How Gabriel Harvey Read his Livy.”

Past and Present

, 129: 30–78.

Lyons, Martyn (1999) “New Readers in the Nineteenth Century: Women, Children , Workers.” In Guglielmo Cavallo and Roger Chartier (eds.),

A History of Reading in the West

, pp. 313– 44. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Reading Experience Database at

www.open.ac.uk/Arts/RED/

St. Clair, William (2004)

The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period

. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Savile, Gertrude (n.d.) “The Commonplace Book of Gertrude Savile.” Nottinghamshire Archives, Nottingham, DD512/212/12.

Saville, Alan (1997)

Secret Comment: The Diaries of Gertrude Savile

. Thoroton Society Record Series 41. Nottingham: Thoroton.

Sharpe, Kevin (2000)

Reading Revolutions: The Politics of Reading in Early Modern England

. London: Ya le Un iversity Press.

Vincent, David (1982)

Bread, Knowledge and Freedom: A Study of Nineteenth-century Working-class Autobiography

. London: Methuen.

— (1983) “Reading in the Working-class Home.” In John K. Watton and James Walvin (eds.),

Leisure in Britain 1780–1939

, pp. 207–26. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

PART II

The History of the Material Text

The World before the Codex

5

The Clay Tablet Book in Sumer, Assyria, and Babylonia

Eleanor Robson

If a book is a collection of pages bound together and sold on the open market, then there were no books in the ancient Middle East. If, on the other hand, a book is a means of recording and transmitting in writing a culture’s intellectual traditions, then there were very many, and there is a rich and extraordinary history of the ancient Middle Eastern book to be explored and told. Although much has been written on the origins and development of early writing in the Middle East (Walker 1987; Nissen et al. 1993), and rather less on archives (Pedersén 1998; Brosius 2003) and libraries (Michalowski 2003; Black 2004), there has been no comprehensive study of writing media, still less on literate intellectual culture. This chapter is a first attempt at such a venture and, as such, I hope that book historians of other periods and places will read it with a certain indulgence. Equally, I write in the hope that colleagues of mine will take up the challenge of taking this project further, integrating the first half of recorded history more fully into the history of the book.

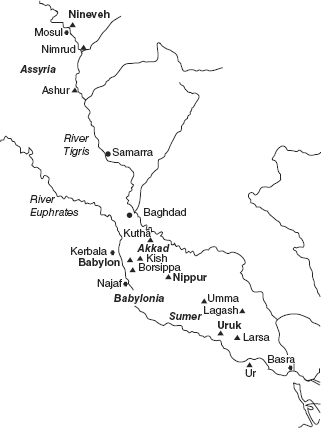

After a brief survey of the mechanics, media, and cultural context of cuneiform writing, I will take three case studies to try to determine whether – and, if so, when, where, and how – we can talk of books in the first three millennia of recorded human history in the Middle East (

figure 5.1

).

Books of Clay? Cuneiform Culture

Writing emerged in the context of temple bureaucracy in the cities of the southern Iraqi marshes some time in the late fourth millennium bc (Nissen et al. 1993). A tiny number of accountants used word signs (usually pictograms) and number signs to account for institutional assets – land, labor, animals – and their secondary products. They wrote on refined clay tablets, about the size of a credit card but around 1 cm thick, incising the signs for the objects they were recording with a pointed stylus and impressing the numbers with a cylindrical one. The front surface of the tablet was marked out into boxes, each one containing a single unit of accounting, logically ordered, with the results of calculations (total wages, predicted harvests, and so on) shown on the back. This writing was barely language-specific – it represented concrete nouns, numbers, and little else, with only occasional clues to pronunciation and none at all to word order – and was known only to a handful of expert users. Its functionality was as yet so limited that it was used only to keep accounts, or to practice writing the words, numbers, and calculations needed for accountancy.

Figure 5.1

Map of ancient Iraq showing major cities.

In the course of the third millennium bc, scribes and accountants expanded writing’s capabilities to record legal transactions and agreements, dedicatory inscriptions to gods, and, finally, narrative texts of many kinds, including letters, accounts of political events, hymns to deities, and incantations (Van De Mieroop 1997). Several innovations were needed to bring this about. Most important was that writing should represent the sounds of words rather than the appearance of objects. At this point, Sumerian becomes visible in the written record. Sumerian is an isolate language whose linguistic relatives, if it ever had any, all died out before they were written down. It is agglutinating: its nouns and verbs are composed of unchanging lexical stems with grammatical particles prefixed and suffixed to them to indicate their function in the sentence. For instance, the phrase

ka egalakshe ngenangune

(“On my arrival at the palace gate”) is composed of the particles

ka

“ga te”;

e

“house,”

gal

“big,”

ak

“of,” and

she

“at”;

ngen

“go,”

a

(nominalizer),

ngu

“my,” and

ne

(verbal phrase marker). The earliest script had been capable only of writing the lexical stems in this phrase –

ka

,

egal

, and perhaps

ngen

– but now punning allowed grammatical particles to be written down for the first time. It thus became essential to write signs in a linear order, both to show which stem particles were attached to and to indicate the order of the words in the sentence.

Paradoxically, the tailoring of early writing to the grammatical particularities of Sumerian also freed it from the necessity of writing Sumerian alone. If signs represented sounds, they could represent the sounds of any language, with some adaptations if necessary. Sumerian’s closest neighbor was the Semitic language Akkadian, an indirect ancestor of Hebrew and Arabic, which today we subdivide into Assyrian, the dialect of ancient northern Iraq, and Babylonian, the dialect of the south.

Not so essentially, but perhaps inevitably, as writing grew to be representational of sounds rather than objects, it became more abstract in appearance too. The scribes developed a new technique of sign formation which entailed pressing a length of reed stylus obliquely into the clay to create linear strokes or wedges; hence our name “cuneiform” from Latin

cuneus

, “wedge.” The size and shape of the tablets themselves also became much more varied, with shape and layout becoming closely associated with function. Indeed, it is often possible to identify the genre of the text on a tablet simply by looking without reading, as, for instance, the five different types of school tablets from House F discussed below.

Cuneiform writing was fully functional by about 2400 bc but remained the preserve of the professionally literate and numerate who were employed by temples and palaces to uphold and manage institutional authority. Later in the millennium, prosperous families and individuals also began to use the services of scribes to record legal transfers of property on marriages, adoptions, and deaths, loans and sales, and the resolution of legal disputes. Cuneiform remained fearsomely complex with some 600 signs in its repertoire, many of which could take one of up to a dozen different syllabic or ideographic values depending on context. It was potentially susceptible to simplification, but in fact grew in complexity over the centuries, ensuring that its use remained almost exclusively in the hands (and the eyes) of highly trained scribes. When alphabetic Aramaic reached Assyria and Babylonia from the west at the turn of the first millennium bc, it was quickly adopted for an increasing range of everyday writings, almost always on perishable media like animal skins and papyrus. Whereas in early Mesopotamia cuneiform literacy had been primarily a tool for controlling the ownership and rights to assets and income (some 95 percent of extant tablets attest to this function), in the first millennium it increasingly became a prestige medium. With cuneiform, the scribes communicated with the gods, learned and created intellectual culture, and wrote certain sorts of legal documents. The last known datable cuneiform tablet is an astronomical almanac from ad 75 (Geller 1997).

For the most part, cuneiform scribes wrote on clay which had been prepared in much the same way as clay for fine pottery production. It had to be levigated, or sieved, to remove particles of stone and plant fiber, and puddled, or kneaded, to remove air bubbles and to increase its elasticity. Tablets could be as small as a postage stamp or (rarely) as large as a laptop computer, but scholarly tablets infrequently contained more than about 500 lines of text. Tablets were rarely baked in antiquity; more usually they were left to dry in the sun. They were filed in archives or libraries on shelves, in pigeonholes, or in labeled baskets. Clay basket tags and shelf records occasionally survive, as do a few acquisition lists from Ashurbanipal’s Library (discussed below), but no complete inventories are known.

When the archival lives of the tablets were over they were recycled by soaking in specialist basins and reshaped. Whole archives and libraries

in situ

are thus found only in exceptional circumstances: the sudden abandonment of a building or city, or accidental conflagration (which, baking the tablets, paradoxically served to aid their preservation). Of the three case studies discussed below, the House F tablets were reused as building material; the tablets in Ashurbanipal’s Library baked in the fires set during the Median sack of Nineveh in 612 bc; and the Rêsh temple’s library was abandoned as the temple itself fell into disuse along with the entire cuneiform tradition.

Clay was not the only medium of cuneiform script. Monumental inscriptions were carved on stone, of course, but from the late third millennium onward there are also textual references to wooden boards with waxed writing surfaces. Almost all of those writing boards, and all of their surfaces, have long since perished along with other organic writing media, but clay tablets have survived in the archaeological record in many hundreds of thousands. Most cuneiform tablets known today are the yield of pre- and proto-archaeological digging in the late nineteenth century, or illicit excavations in the twentieth. Their original contexts can to some extent be recovered from internal evidence from the tablets themselves, in conjunction with the acquisition records of the museums and collections that house them. But controlled and documented archaeological excavation of textual objects

in situ

inevitably reveals far more than the historical record alone about the practices of creating, using, storing, and destroying cuneiform tablets. It enables us too to situate tablets in socio-intellectual contexts of production, communication, and preservation that allow them to be considered within the world history of the book.

School Books in Bronze Age Sumer?

When is it meaningful to talk of “clay tablet books,” as in the title of this chapter? Cuneiformists have traditionally divided tablets into two discrete genres. Much the largest consists of archival tablets: utilitarian documents with limited shelf-life that together comprised complex administrative and/or legal systems. Memoranda, letters, accounts, receipts, rosters, court records, legal documents: they all have their counterparts in more recent literate cultures, and intuitively we can say that these records and documents are not in themselves books. More interesting for our purposes are those tablets that Leo Oppenheim famously described as transmitting the “stream of tradition,” or the intellectual culture of ancient Mesopotamia. Their contents range from literature and poetry to magic and medicine, although on closer inspection these modern genre designations often prove inadequate to capture the intellectual content and social function of such texts. But what they have in common is the fact that they were memorized and/or copied from generation to generation, often over millennia, collected and edited and commented upon. Such tablets embody the production of knowledge in ancient Iraq and thus have first claim to being considered in the light of book history.

In the Bronze Age (c.3000–1200 bc in the Middle East) the production and transmission of literate knowledge was sited in scribal schools. No doubt temples, courts, and other places were also centers of intellectual and cultural exchange at this time, but they have not yet been identified and analyzed as such through the archaeological record. Second-millennium schools, on the other hand, have been carefully studied in recent years, enabling us to look at them in the light of book history. For instance, in the early 1950s over a thousand tablets, mostly in fragments, were excavated from “House F,” a small urban house in Nippur near modern Najaf (Robson 2001). According to the datable household documents found in it, House F was used as a scribal school in the 1740s bc, immediately after the reign of Hammurabi (1792–1750

BC

), most famous of the early Babylonian kings.

About half of the tablets in House F are the by-products of an elementary scribal education. They take the trainee from learning how to use a stylus to make horizontal, vertical, and diagonal wedges on the tablet to writing whole sentences in literary Sumerian. The students doubtless learned to make their own tablets too, because in the corner of the tiny courtyard was a bitumen-lined basin filled with a mixture of fresh tablet clay and crumpled up tablets waiting to be recycled. Both the elementary exercises and the tablets themselves were standardized, with format and content closely related to pedagogical function.

The tablets were made in just five shapes and sizes. Most interesting and useful for historians are those now called Type II tablets (

figure 5.2

), which are typically half the size of a hardback novel (Veldhuis 1997). They were designed to give the scribal student first exposure to a new exercise, through repeated viewing and copying of a 10–20-line extract on the obverse, and revision through recall and writing from memory of a longer section of an earlier exercise on the reverse, often explicitly joining the new onto the end of the old. No other tablet type is dual-function; but like the obverse of Type II tablets, Type III and Type IV tablets are witnesses to the early stages of students’ learning a new piece of work. Type I tablets and Prisms (long four- or six-sided tablets), like the reverse of Type II tablets, were probably written as the student recalled and wrote out a whole piece of work, or a significant section of it, before moving on to acquire new knowledge.