A Companion to the History of the Book (15 page)

Read A Companion to the History of the Book Online

Authors: Simon Eliot,Jonathan Rose

Ashurbanipal’s younger brother Shamash-shumu-ukin had been designated prince regent of Babylonia by their father Esarhaddon. In 652 bc he rebelled against Assyria, claiming Babylonian independence. Ashurbanipal responded by declaring war, which ended four years later in Assyrian victory. Fragmentary library acquisition records from Nineveh, dated 647 bc, detail the contents of a large number of scholarly tablets and writing boards from various named towns and individuals in Babylonia (Parpola 1983), presumably booty or tribute, while a contemporary letter reports on the writing activities of several captive Babylonian scribes: “Ninurta-gimilli, the son of the governor of Nippur, has completed the Series [of celestial omens] and been put in irons. He is assigned to Banunu in the Succession Palace and there is no work for him at present. Kudurru and Kunaya have completed the incantation series ‘Evil Demons.’ They are at the command of Sasî.”

Recent cataloguing in the British Museum has enumerated some 3,700 scholarly tablets from Ashurbanipal’s Library written in Babylonian script and dialect – about 13 percent of the entire library (Fincke 2004). Ashurbanipal’s obsession with Babylonian books did not, then, completely overwhelm indigenous production, but he did view them as highly valuable cultural capital: their forced removal to Nineveh undermined Babylonian claims to the intellectual heritage of the region and thus pretensions to political hegemony, while reinforcing Ashurbanipal’s own self-image as guardian of Mesopotamian culture and power.

Books and Professional Identity in Hellenistic Babylonia

After the collapse of the Assyrian empire in 612 bc, Babylonia regained its independence for some seventy years, only to be conquered by the Persians (539

BC

) and, much later, by Alexander the Great (330

BC

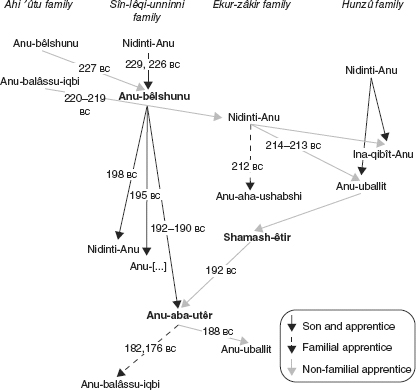

) and his Seleucid successors. Despite losing political autonomy, Babylonia retained a large share of cultural, religious, and intellectual independence, particularly in the priestly and scholarly communities based around the urban temples. This last case study examines the scholarly tablets belonging to one Shamash-êtir of the Ekur-zâkir family, the chief priest of the great sky god Anu in the southern Babylonian city of Uruk in the 190s bc. The colophons of his tablets enable us to situate him in a kin-based professional context, within a five-generation continuous tradition of priesthood and book-learning (

figure 5.5

; Robson forthcoming).

Shamash-êtir is named on nine surviving tablets that he owned or wrote. At first sight, they are an eclectic mix. As might be expected, two contain instructions for the performance of rituals in Anu’s temple Rêsh: for the four daily meals of the gods; and for the night-time rituals of the autumnal equinox. Both are part of the copied tradition. The latter is explicitly stated to have been “written and checked from an old writing board,” while the colophon of the food ritual tells a narrative of its capture in the mid-eighth century, followed by rescue in c.290 bc by one of Shamash-êtir’s ancestors. But there are also six tablets of mathematical astronomy, containing complex instructions for the calculation of dates and positions of key events in the journeys of Mars, Jupiter, and the moon across the night sky, and tabulations of those data. None of the colophons suggest that they are copies of older works; the predictive tables certainly, and perhaps even the mathematical methods, are original compositions. Finally, Shamash-êtir was the scribe of at least one legal document, recording the purchase of shares in temple income by one Anu-bêlshunu, descendant of Sîn-lêqi-unninni (the legendary editor of

Gilgamesh

) and a lamentation priest of Anu, which was witnessed by nine named members of four different families.

Figure 5.5

Shamash-êtir’s intellectual network.

Shamash-êtir copied the equinoctial ritual for an older man named Anu-uballit of the Hunzû family, while four of the astronomical tables were written for him by Anu-aba-utêr of the Sîn-lêqi-unninni family. Both men wrote other surviving scholarly tablets too. The dates of the tablets, where known, suggest that younger men wrote tablets for older established scholars as part of the apprenticeship process (Gesche 2000). As far as we can tell, this was the only circumstance in which scholarly tablets were produced or reproduced in Hellenistic Uruk. Anu-uballit Hunzû was educated by two different men in the 210s bc. From his father he learned lots of alternative rules of thumb for the short-term prediction of ominously significant phenomena, such as the timing of lunar eclipses or the length of the following lunar month; from Nidinti-Anu Ekur-zâkir (and thus an older relative of Shamash-êtir) he learned the 70-chapter celestial omen series

Enûma Anu Ellil

(“When the gods Anu and Ellil”) and the equally long standard sacrificial omen series

Bârûtu

(“Extispicy,” divination from the configuration of sacrificed animals’ entrails). The form and content of both series had been standardized by at least the seventh century bc, and are well known from Ashurbanipal’s Library. Apart from the four astronomical tablets, Shamash-êtir’s pupil Anu-aba-utêr Sîn-lêqi-unninni wrote seven surviving tablets for his father in the late 190s bc, just after he was writing for Shamash-êtir; five were written for him shortly afterwards by Anu-uballit Ekur-zâkir (presumably a young relative of Shamash-êtir’s). He also owned or wrote five others, including two copied by a nephew in the 180s and 170s. Over two-thirds of his tablets contain computational astronomy; the remainder is made up of incantations, zodiacal calendars, and a collection of mathematical problems (

figure 5.6

).

The colophons thus enable us to situate Shamash-êtir within five generations of scholars over a forty-year period, c.215–175 bc. While it is perhaps dangerous to make too many inferences from such a small dataset (and it is but a subset of the known scholarly corpus from Hellenistic Uruk), some intriguingly suggestive patterns can be seen. First, there appears to be a striking shift in the type of astronomy transmitted (Rochberg 2004). While the second generation apparently learned only short-term prediction methods based on simple periodicities, the fifth generation was exclusively trained in sophisticated computational methods. The middle generations were involved in both approaches as well as horoscopy. And while traditional omen collections were copied only by the older men, there was a consistent preservation of the temple rituals and cult songs across the generations. The younger members of the Sîn-lêqiunninni family added injunctions to the colophons of their astronomical tablets, such as “Whoever fears Anu and Antu shall not deliberately take it away.” This suggests that the restricted circle of scholars that we infer from the colophons was strictly enforced in practice: a tiny number of men from a tiny social group were allowed access to this material.

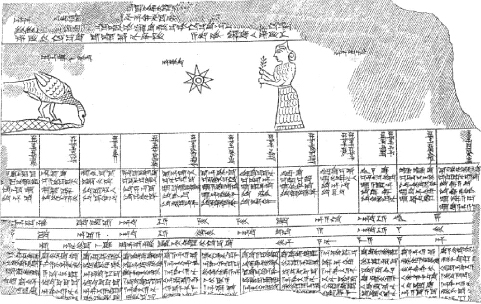

Figure 5.6

A tablet from Hellenistic Uruk, written by Shamash-êtir’s apprentice Anu-aba-utêr in 192 bc, depicting constellations including Hydra and Virgo.

In fact, just three families were involved in this intellectual network. Indeed, taking the entire Hellenistic scholarly corpus into account would at least double the number of individuals involved, but add only one further family: the descendants of Ahi’ûtu. Shamash-êtir’s intellectual world was also embedded within his social circle. In the legal document he wrote, the buyer of the prebend was no other than the father of his apprentice Anu-aba-utêr, while seven of the nine witnesses were from the Ahi’ûtu and Hunzû families. The seller and remaining witnesses are from just two further families: the descendants of Kurî and Lushtammar-Adad. We also know of several intermarriages, between the Hunzûs and Ekur-zâkirs, and between the Lushtammar-Adads and Ahi’ûtus.

The colophons of their tablets reveal that all of Shamash-êtir’s scholarly associates were priests of one kind or another: after their apprenticeships, the Hunzûs and Ekur-zâkirs all carried the title “incantation priest of Anu and Antu,” while the Sîn-lêqi-unninnis were “lamentation priests of Anu and Antu” (McEwan 1981). The Rêsh temple was uncovered during the course of long-running German archaeological excavations at Uruk. It may date back to the seventh century bc, but the excavated building is all attributable to work in 202 bc. It was a truly monumental construction of baked and mud brick, towering over the city. Anu and his divine spouse Antu’s shrines, which backed on to an enormous mud-brick ziggurat some 10 0 m square, were the focus of the complex, but the Rêsh also housed at least twenty further chapels and installments for divine statues. In one storeroom, which had already been subject to clandestine excavations, were found nearly 140 cuneiform tablets dated to 322–162 bc: hymns and rituals, as one might expect, but also horoscopes, collections of omens, and astronomical works, as well as a significant number of legal documents. Several of the scholarly tablets belonged to Shamash-êtir’s apprentice Anu-aba-utêr, and it is widely agreed that many of the other tablets discussed in this section were illicitly dug from this area too.

Finally, there is the conundrum of the scholars’ astronomical activity to solve. It is clear to see why, as priests, they would need to possess and understand the complex temple rituals (Linssen 2003). But as the primary object of their worship was Anu, the sky god, many of those rituals had to be performed at celestially significant times. Some of those were a regular part of the calendar, such as the equinoctial rituals. Others, such as the propitiatory rituals for placating the gods during the disruptive repair of their temples, had to be performed “on a propitious day, in a propitious month,” when the sun, moon, and planets were in auspicious configurations in the sky. And, finally, on the occasion of particularly inauspicious celestial events, such as lunar eclipses, the priests were charged with soothing the angered gods through ritual public lamentation. All of these rituals were elaborate and costly, requiring much preparation and expenditure, such as in the ritual manufacture of kettle-drums. On one infamous occasion in 531 bc, the lamentation priests of Uruk, all from the Sîn-lêqi-unninni family, had been the subject of an official temple enquiry after a lunar eclipse they had lamented over had not taken place. That put an onus on succeeding generations dramatically to improve their predictive ability – and jealously to guard their knowledge as inherited professional secrets. Shamash-êtir and his colleagues, while upholding the age-old ritual traditions, were still improving their astronomical methods, generation by generation, so that they could be confident of fulfilling their priestly duties on time, every time without embarrassment to their professional and familial heritage or their temple. In the end, though, new beliefs won out and the Rêsh – and cuneiform scholarship itself – went into terminal decline.

Conclusions: Re-reading Tablets in the Light of Book History

I have attempted to avoid generalizing about the three thousand years of cuneiform culture by taking three very different case studies to shed light on the variety, individuality, and fluidity of scholarly literacy and numeracy in the ancient Middle East. The early intellectual tradition was predominantly one of oral transmission, with repeated copying for memorization, in which tablets functioned essentially as ephemera. By the beginning of the Iron Age in the later second millennium bc – unfortunately, a period badly understood archaeologically – cuneiform tablets (and presumably also perishable writing media) begin to reflect concerns with textual stability, genre, and editing, which might lead us to think about them as “books.” In the first millennium bc, acquisition of such “books” is attested by inheritance, conquest, and copying. Costs of production were minimal: the easily available raw materials were presumably procured and prepared by junior apprentices, while the writing itself was carried out by captives (in the exceptional Assyrian case) or by apprentices as part of their training (as in Hellenistic Uruk). There was no sale market as far as we know, although sales of movable objects were not subject to written contracts, so it is equally fair to say that we have no evidence for the sale of food. Cuneiform literacy was by and large restricted to tiny handfuls of professionals – supported through royal patronage or by inherited positions in the independently wealthy temples – who were both consumers and producers of books. Yet the know ledge containe d in books could have political power as well as professional import.