A Companion to the History of the Book (18 page)

Read A Companion to the History of the Book Online

Authors: Simon Eliot,Jonathan Rose

The old concept inherited from classical Athens that a good person is a person who knows a lot is still at work here. It is in this light that the novel, a new literary form that came into being around the turn of the first century bc, can be considered as a form of text that gives even those who are less educated, and are unable to understand and enjoy the “great works,” something to read. Those reading the novels who had a good education would enjoy identifying numerous allusions to the great works of the past, but others who were not able to do so could just enjoy them for the story.

The old curriculum of reading, based on a progression from Homer to the orators, lasted long into the Christian era. However, the canon was gradually reduced to fewer and fewer works. Of Homer, the

Iliad

was considered more fruitful for a moral education, and most examples we have on papyrus come from the first book of that epic. Of the comedies of Aristophanes, only eleven survived into the medieval period, and of Menander’s plays, none made it past the end of the sixth century, even though the so-called

Sententiae Menandri

had a splendid career long after. These short maxims applicable to the everyday lives of all sorts of people were more fitting for readers who sought moral help, rather than education, from literature. The Bible had, between the fourth and fifth centuries, become the main text for education. When St. Basil the Great tells his nephews about the ideal education, he still advises them to read classics like Homer and Hesiod, but adds that younger readers should be given only what is “useful” as long as they cannot fully appreciate the holy words of the Bible (

Oratio ad adolescentes

ii. 7).

For book production, these tendencies meant a steady narrowing of titles being copied. Texts not considered of value any more were not copied from the old form of the roll to the new form of the codex. Most of the Greek lyric poets, except Pindar, did not make it into codex form. The next barrier at which many authors disappeared occurred in the eighth century ad when texts began to be copied in the new form of minuscule writing. At that stage, Sappho too was left behind.

Codex-type books became increasingly popular after the second century ad. The reasons why readers now wanted to have books in this new form, and chose to abandon the old form of the roll, will have been manifold. First, practical reasons can be adduced: there is no doubt that a codex is less fragile than a roll. The pages of a book, lying flat on top of each other, form an item more solid than a fragile roll wound round and round itself. A codex also has greater capacity, since its pages are written on both sides. It can also be easily opened, closed, and opened again at the same page, whereas a roll has to be rolled back completely after use. Thus, the codex also provided random access to any part of the text required, as opposed to the linear access of the roll (in our age, the videocassette offers only linear access, while a DVD offers random access).

It is striking that the change from roll to codex goes hand in hand with the change from the pagan religions to Christianity. All early examples of New Testament texts from the second century ad are written in papyrus codices and not on rolls. Here, ideological motives may be important besides the practicality of the new form. The Old Testament, the holy book of the Jews, had always been written on rolls. Christians may have wanted their holy book to look different from the Torah. The notebooks that the Apostle Paul used and mentioned in his epistles, small booklets made of parchment, may have been considered the right form for the books of humble people, a status desirable to many Christians. Later, the Codex Sinaiticus and the Codex Alexandrinus, luxury copies of the Bible written on parchment in the fourth century, were to make a very different point. By the fourth century, the holy scriptures had become a book that was expected to reflect the holiness and value of its content.

There are only few examples of illustrated books from antiquity. It is obvious that the insertion of drawings into the text required a special skill that the scribe who copied the text may not have possessed. Indeed, a private letter from late antiquity shows clearly that the copying of the text and the illumination of the pages were carried out by different people. Illumination of the text in the sense of ornamentation of the pages did not exist in the Greco-Roman world before the Christian area. The only examples of drawings and pictures in books from the earlier periods are illustrations that help to explain the text or give a visual counterpart to the text, like personae who appear in plays or geometrical figures in scientific treatises. The idea of putting ornaments at the beginning of a chapter or in the margins of a page, which we find so often in medieval and later manuscripts, developed only when the text copied was seen as an object sacred in its own right, the value of which could be emphasized through ornamentation. It is at this time that the scribe’s work started to become more and more valued, as it came increasingly to be seen as a sacred task. Scribes now began to put their names under the text when they had finished copying it.

References and Further Reading

Basilius (1984)

Oratio ad adolescentes

(Greek, Latin, and Italian), ed. M. Naldini. Florence: Nardini.

Černý, J. (1952)

Paper and Books in Ancient Egypt

. London: H. K. Lewis.

Emery, W. B. (1938)

The Tomb of Hemaka, Excavations at Saqqara

. Cairo: Government Press.

Immerwahr, H. R. (1964) “Book Rolls on Attic Vases.” In C. Henderson (ed.),

Classical, Medieval, and Renaissance Studies in Honor of B. L. Ullman

, vol. 1, pp. 17–48. Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura.

— (1973) “More Book Rolls on Attic Vases.”

Antike Kunst

, 16: 143–7. Olten: Urs Graf Verlag.

Janko, R. (2002) “The Derveni Papyrus: An Interim Text.”

Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik

, 141: 1–62. Bonn: Habelt.

Johnson, W. A. (2004)

Bookrolls and Scribes in Oxy-rhynchus

. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Lewis, N. (1974)

Papyrus in Classical Antiquity

. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

P

.

Oxy

. 2192 (1941)

The Oxyrhynchus Papyri XVIII

, ed. E. Lobel, C. H. Roberts, and E. P. Wegener. London: Egypt Exploration Society.

P

.

Petaus

30 (1969)

Das Archiv des Petaus

, ed. V. Hagedorn, D. Hagedorn, L. C. Youtie, and H. C. Youtie. Cologne: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Pliny the Elder (2000)

Naturalis historia

. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Roberts, C. H. and Skeat, T. C. (1983)

The Birth of the Codex

. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Thomas, R. (1989)

Oral Tradition and Written Record in Classical Athens

. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Turner, E. G. (1980)

Greek Papyri: An Introduction

. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

— (1987)

Greek Manuscripts of the Ancient World

, 2nd edn., revised by P. J. Parsons. London: Institute of Classical Studies.

The Book beyond the West

7

China

J. S. Edgren

Script appeared in China more than four thousand years ago. China’s distinctive non-alphabetical script has been found on many kinds of ancient objects that are not books: written on pottery, engraved on animal bones (especially bovine) and tortoise shells, and cast on bronze vessels, from the Shang dynasty (circa fourteenth to eleventh centuries

BC

) to the Western Zhou period (eleventh century to 771

BC

). Other portable bronze objects that bear brief inscriptions include weapons, mirrors, coins, and seals. The use of seals began in the Eastern Zhou period (770–221

BC

) and continued throughout the Han dynasty (206

BC

–

AD

220). Early seals were often made of iron or bronze as well as gold, even jade and other precious stones, and impressions were usually made in soft sealing clay. Other text-bearing objects include inscribed monuments, such as the “stone drums” (not later than fifth century

BC

), so called because of their shape, and various commemorative stelae from the Han period onward.

The

jiance

or

jiandu

, a roll of thin bamboo or wooden strips inscribed by brush with indelible ink and fastened in sequence by cords, may be considered the earliest true book form in China. These books came into existence no later than the sixth century bc, and extant specimens date from the late Warring States period (403–221

BC

) through the Han. Archaeological discoveries of

jiance

hoards in recent decades have greatly enhanced early historical and textual studies. As early as the fifth century bc, books were commonly referred to as

zhubo

(bamboo and silk), which points to the use of silk as a writing material. Silk books were also in the form of scrolls. The

jiance

arrangement of text from right to left in narrow vertical columns further influenced early manuscript copying on silk and paper. Eventually, the custom left its mark on the layout of manuscript books and on the printed page (

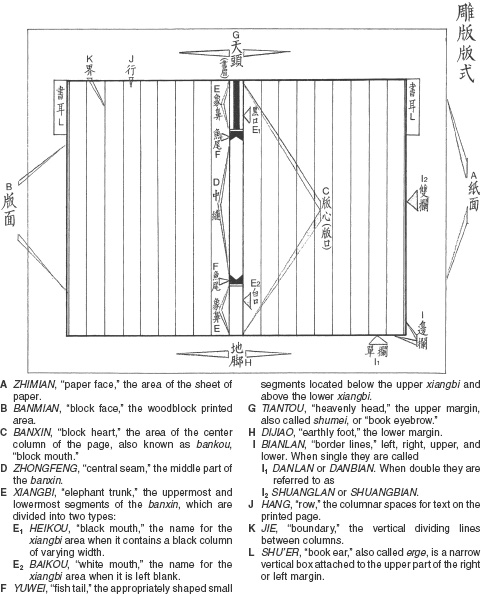

figure 7.1

).

An important

jiance

book of wooden strips from Juyan from the end of the first century

AD

was found intact, and it can be noted that the text was written before the strips were fastened (i.e., bound) together, resulting in some characters being covered by the hemp cord. The Han dynasty cache of wooden and bamboo inscribed strips found at Wuwei in Gansu province in 1959 is particularly significant. The text of the classic

Yili

(Book of Etiquette and Ceremonial) has spaces between characters where the cord was tied, implying that the roll was constructed before the text was copied. Chapter number and name are indicated on the two outer strips of each roll, and a column number, somewhat akin to modern pagination, is written at the foot of each column. Compared to bamboo and wooden strips, silk was a more valuable material and appears to have been reserved for important texts and for illustrated works (Tsien 2004).

Figure 7.1

Standard format of traditional Chinese printed books and manuscripts (unfolded leaf). From S. Edgren (ed.),

Chinese Rare Books in American Collections

, New York, 1984. Reproduced by courtesy of the China Institute in America.

It is necessary to consider the possibility of the existence of

jiance

as early as the Western Zhou, or even the Shang. It so happens that the Chinese character

ce

, in

jiance

, is the common one for a volume or fascicle of a book, and its ancient graph is clearly a picture of three to five thin vertical strips intersected transversely by a circular threadlike line. The graph for

ce

as well as the one for

dian

, a related character showing

ce

as a presumed offering, occur in ancient bronze and oracle bone inscriptions, which has led to the assumption that books existed as early as this in China. Furthermore, the

Shangshu

(Book of Documents), an important ancient Chinese text, confirms that

ce

and

dian

existed in the Shang. If any archaeological evidence is forthcoming for the existence of bamboo or wooden strips with writing in the Shang, it is likely that the inscriptions will be limited to the sort of simple records we know from oracle bones and bronzes. After all, what surely contributed to the probable advent of the book in China around the sixth century bc was the rise of literary production in the Spring and Autumn period (722–481

BC

) of the Eastern Zhou.

The earliest Chinese books of bamboo or wooden strips, however practical they may seem, became heavy and awkward when a complete text was assembled, and they were not conducive to the wide circulation of texts. The important silk books discovered in the early Han tomb at Mawangdui clearly were luxury products. It was not until after the invention and development of paper in China during the late Han period that the book could begin to rise above these limitations, and it took a few more centuries before books of paper replaced those of bamboo and silk. The invention of paper is usually associated with the Han eunuch Cai Lun (d.

AD

114), who presented his method of paper manufacture to the emperor in

AD

105, although we know that true paper existed at least two centuries prior to this date (Tsien 1985). According to Cai’s biography in the

Hou Hanshu

(History of the Later Han,

AD

25–220), he reported that, as writing materials, “Silk is dear and bamboo heavy, so they are not convenient to use. [Cai] Lun has the idea to use tree bark, hemp, rags, and fish nets to make a silk-like writing material” (Zhang 1989: 8). The significance of paper as the most important material for the evolution of book forms, in China and elsewhere, cannot be overstated.

The earliest manuscript books of paper were made by horizontally pasting sheets of paper on end in the form of

juanzizhuang

(scroll binding) or

juanzhouzhuang

(scroll and rod binding), clearly in imitation of the forms they were superseding. The scrolls opened on the right and rolled out to the left and, at the very end of the text, a wooden rod might be attached on which the scroll could be tightly rolled. Sometimes vertical lines, outlining columns for the text, were lightly traced on the surface. Coexisting with these early manuscript scrolls of paper were an ever-decreasing number of manuscript scrolls of silk.

Although paper itself was viewed as an inexpensive substitute for silk, the particular characteristics of paper, such as receptivity to folding, came to be recognized, and by the early Tang dynasty (618–907) the

jingzhezhuang

(sutra-folded binding, sometimes called accordion or concertina binding from its appearance) was in use in China. It was simply made by folding sections of a scroll at regular intervals to form a flat, vertically elongated rectangular volume. The chief advantage of the sutra-folded binding was that it afforded direct access to any section of the text. This style is believed to have been influenced by the Indian palm-leaf manuscript books (

pothî

) imported to China and adjacent central Asian territories by early Buddhist travelers. While it is altogether plausible that knowledge of palm-leaf books had some influence on the transition from rolled sheets of paper pasted on end to form a scroll to folded sheets of paper joined in the same manner, it is equally likely that the natural act of folding was intuitively understood directly through handling the paper. The sutra-folded binding represents the first codex form in China.

Once it was understood that the leaves of a book need not be attached continuously, the size and shape of books began to reflect the natural form of a sheet of handmade paper, limited as it was by the arm span of the papermaker. The next phase was represented by the

hudiezhuang

, or butterfly binding, which was achieved by folding each printed sheet in the center, text folded inward, and then pasting each sheet together at the fold to form the spine of the book. Each page thereby had three margins: upper, lower, and outer. Stiff paper covers were added with a band of paper or cloth covering the spine. This form was devised in response to the development of woodblock printing in the late Tang and early Song (960–1279). Partly from economic motives and partly from the use of a wider variety of raw materials, thinner and more absorbent papers began to be used for book printing, and these papers often were too limp to be rolled or folded. Moreover, xylographic printing did not employ a press, but instead applied pressure by rubbing the back of a sheet of paper that had been laid face down on an inked printing block. Rubbing the already-printed side to produce an impression on the other side of the paper would inevitably disturb the text, so one side of the sheet had to be left blank. In addition to the inconvenience of pairs of printed pages alternated with pairs of blank pages, the use of paste in the area of the spine of the book made butterfly binding attractive to insects. Furthermore, if leaves became detached through reading, the center column might be damaged and the leaves were not easily reattached.

The wrapped back binding, or

baobeizhuang

, simply reversed the process used for the butterfly form. By folding the sheet at the center column, but this time with the text facing outward, there were three margins left on the page: upper, lower, and inner. The text block was fastened by means of two or more twisted spills made from sturdy long-fibered paper, which were threaded through holes pierced along the inner margin. Thus the text extended out as far as the foredge of the book. A single sheet of durable paper or cloth, or a combination of separate cover sheets and a strip of material for the back, was used to form the covers and wrap the back: hence the name. The resulting volume could be shelved horizontally with the spine to the right and the foredge to the left, and it was popularly used in the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) and the first half of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). This book form was created to overcome the disadvantages of the butterfly form by strengthening the foredge and outer corners by folding the sheets there, by concealing the blank sides of the sheets inwardly, and by eliminating the potentially harmful paste used along the center column folds.

The next and final stage in the evolution of the traditional book in China was the familiar form of

xianzhuang

or thread binding. It evolved directly from the wrapped back binding during the Ming, and it simply resulted from removing the strip of paper or cloth covering the spine, piercing holes along the spine, and externally stitching the covers in place with silk thread. The advantages of thread binding were that it used virtually no paste and produced a lightweight, flexible fascicle that could be easily repaired or rebound without any loss or damage to the original form. This method predominated among new books published during the late Ming and throughout the Qing period (1644–1911), for more than four centuries. In fact, very few older books escaped being rebound in this manner, leaving us with a paucity of original early book bindings for study. There is an outstanding technique for rebinding

xianzhuang

volumes called

jinxiangyu

(jade inlaid with gold), which involves interleaving the entire book with intricately folded fine white paper in such a way as to produce new protective borders on all sides but the folded foredge.

The very characteristics described here that make Chinese books so desirable – that they consist of thin, lightweight fascicles whose parts are replaceable and whose production methods are reversible – also imply a degree of vulnerability. Chinese books must be handled with awareness of their special qualities and, unlike their Western counterparts, which have protective covers firmly attached to the text block, they are well served by a variety of detached protective coverings. As a general rule, in the earlier period books had durable or stiff covers and the fascicles were protected by soft coverings, such as wrapping cloths. Later, as the paper covers of bound fascicles became thinner and more vulnerable, especially after the introduction of thread binding, the covering materials became firmer and more protective. The most common means of protecting thread-bound fascicles is the

shutao

, generally called

hantao

, or folding book case. It is made of pasteboard, lined with paper, and covered with cloth, blue cotton for ordinary books and elaborate silk brocades for rare books. The

shutao

are less favored in the hot and humid climate of southern China, where mold is a serious threat to paper and cloth. Moreover, the paste used in the folding cases can attract insects and rodents. An alternative method for protecting thread-bound books and keeping them together are

jiaban

(clamping boards), which use no paste and expose the volumes to circulating air on four sides. An extremely effective means of protection can be provided by

muxia

(wooden boxes), ranging from plain and simple ones to superior ones made of rare and fragrant woods (Helliwell 1998).