A Companion to the History of the Book (21 page)

Read A Companion to the History of the Book Online

Authors: Simon Eliot,Jonathan Rose

Reed, Christopher (2004)

Gutenberg in Shanghai: Chinese Print Capitalism, 1876–1937

. Vancouver: U

BC

Press.

Tsien, Tsuen-hsuin (1984) “Technical Aspects of Chinese Printing.” In Sören Edgren (ed.),

Chinese Rare Books in American Collections

, pp. 16–25. New York: China Institute in America.

— (1985)

Paper and Printing

(Science and Civilisation in China, ed. Joseph Needham, vol. 5: 1). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

— (2004)

Written on Bamboo and Silk

, 2nd edn. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Zhang, Xiumin (1989)

Zhongguo yinshua shi

[History of Chinese Printing]. Shanghai: Shanghai renmin chubanshe.

8

Japan, Korea, and Vietnam

Peter Kornicki

Japan

Like Korea and Vietnam, Japan had no writing system before the encounter with Chinese script in the sixth century, when Chinese Buddhist and Confucian texts were first brought to Japan. The earliest texts were therefore written in Chinese, which remained the language of learning until the nineteenth century. In the seventh and eighth centuries, vast quantities of Chinese Buddhist manuscripts were brought back to Japan by scholar monks and then copied for domestic use; the holdings of Japanese monastic libraries at the time often included thousands of titles from the Chinese Buddhist canon and easily exceeded the norms of medieval European monastic libraries. The basic texts of the Chinese Confucian tradition and the key literary works were also transmitted to Japan and they became the keystone of the education system for over a thousand years, exerting profound influence on ethical norms and social values. In the ninth century, a syllabic script known as

kana

was developed for writing Japanese, and it was used for court poetry and romances such as the

Tale of Genji

(early eleventh century). It was sometimes known as the “women’s hand,” but it was used by both men and women for writing poetry at least, while Chinese continued to be used by men for official documents, education, and diaries.

By the mid-eighth century, the technology of xylography, or woodblock printing, had also reached Japan from China, where it had been developed in the seventh century or earlier. The first evidence of printing in Japan comes from the years 764–70, when at least a hundred thousand, and possibly as many as a million, copies of a Buddhist invocation in Chinese were printed in Nara. These were then inserted into miniature wooden pagodas, and many thousands of these survive with their contents intact. Although indubitably the first instance of mass-production printing in the world, these invocations are evidence not of the printing of texts for the benefit of readers but of printing as a ritual act, for the point was simply the multiple production of copies of the text. They were not for reading or even distribution: the pagodas with their contents were stored in temples and not examined until the nineteenth century. Ritual printing of this sort was practiced in Japan occasionally over the ensuing centuries, while printing for reading in Japan can be dated to no earlier than the eleventh century, when Buddhist commentaries and doctrinal works in Chinese were first printed.

Over the next four centuries, printing was undertaken spasmodically, for the most part by the great monastic institutions. Almost all the works printed were Buddhist texts and in Chinese. A few secular works in Chinese, the Confucian canon and medical texts, were also printed, but by secular printers. However, the classic works of Japanese literature were not printed until the seventeenth century, probably because the court society which had produced and transmitted them remained hermetic; another factor was the close association between calligraphy and literature which printing would have threatened. In spite of the growing familiarity of printed books, both through domestic production and through imports from China, there is until the seventeenth century no trace of a book trade or of the kind of commercial printing that had already established itself in China.

At the end of the sixteenth century, typography reached Japan from two sources, almost simultaneously. In 1590, the Jesuits brought from Macao a printing press and established a missionary press which printed not only almanacs and devotional works in Latin, but also some Japanese works in specially cast Japanese type. Later, in the 1590s, Japanese troops who had participated in an invasion of Korea brought back a Korean printing press as booty. Within a decade, both the emperor and the shogun had experimented with this new technology to print secular books in Chinese, and this served to liberate printing from the monasteries. In the first years of the new century, the renowned calligrapher Honnami Kôetsu, with the financial backing of a wealthy entrepreneur, produced exquisite typographic editions of the

Tales of Ise

(tenth century?), Noh plays, and other Japanese works using ligatures to represent the flow of calligraphy and colored papers to enhance the aesthetic effect. By the 1620s, there were commercial printer–publishers in Kyoto producing books in Japanese as well as Chinese, and using both typography and woodblock printing technology. However, during the 1640s, typography went into a decline and woodblock printing predominated until the 1880s. The decline of typography was due to a number of factors: the large quantities of type needed for printing Japanese, amounting to thousands of different pieces given all the characters as well as the

kana

; the calligraphic possibilities of woodblock printing; the greater ease, in the case of woodblock-printed books, of including illustrations and textual glosses to make texts more accessible to less-sophisticated readers; and the ease of responding to slow markets with woodblocks, which could be used to print to demand.

With the seventeenth century, then, came the emergence and rapid growth of commercial publishing. It started in Kyoto, but rapidly spread to Edo (modern Tokyo) and Osaka, and by the end of the century to most of the larger castle-towns. By 1650, most of the canon of Japanese literature had been printed, mostly with monochrome woodblock illustrations, and new works were being written for print, from letter-writing manuals for women to guidebooks and popular fiction. Contemporaries wrote of a flood of publications, and in the 1660s the book trade began issuing classified catalogues of books in print. By that time, booksellers in Kyoto, Edo, and Osaka had already formed themselves into exclusive guilds to protect themselves against copyright disputes. It was at this time, too, that the first censorship edicts were promulgated; these were vague, but the import was to prevent the publication of erotic or sensational books, of any books that even mentioned Christianity (which was proscribed), and of any books which featured the shogun or his officials even if the intent was to praise. In the 1720s, these regulations were tightened up and the guilds were made responsible for their enforcement, but overall the hand of censorship was light in the Edo period (1600–1868) compared with more recent times.

Although reliable estimates of literacy rates are wanting, it is evident that the number of readers was growing rapidly in the seventeenth century. This applied to women, too, for male complaints about women wasting their time reading romantic fiction when they should be reading improving books were on the increase. By the 1660s, “women’s books” had become a category in the booksellers’ catalogues, and numerous books – moralistic, practical, or simply entertaining – were being published explicitly for women readers. There were no public libraries until the late nineteenth century, but booksellers began to undertake commercial book-lending, and colporteurs took books around rural villages offering them for sale or rent.

Although print dominated the production of books in the Edo period, it should not be supposed that manuscript traditions died out. There were three main reasons for the continued production of manuscripts: first, the demand for calligraphically and aesthetically pleasing copies of works of Japanese literature such as the

Tale of Genji

and the canonical poetry anthology

Kokinshû

(905), which were often prepared as wedding gifts; secondly, the desire not to publish commercially sensitive information such as medical advances or new techniques in flower arrangement, which were commonly recorded in manuscripts available only to followers of the teacher who had devised them; and, thirdly, the demand for books on proscribed topics, including political scandals. The last category was particularly large, and judging from the fact that a printed catalogue of them survives and that many extant copies bear the seals of book-rental merchants, they seem to have been popular and to have circulated widely.

With two exceptions, Japan was self-sufficient in books in the Edo period. The first exception was books imported from China via the only open port, Nagasaki. There was a constant supply, including canonical works and commentaries on them, but, increasingly, vernacular fiction too. In the mid-nineteenth century, there were accounts of the Opium Wars and Chinese translations of books on Western geography, which furnished crucial information in the years before 1858 when Japan signed its first trading treaties with the West. The other exception was Dutch books, which entered Japan through the outpost of the Dutch East India Company in Nagasaki, mostly from the beginning of the eighteenth century. Some Japanese became proficient in Dutch, and by the end of the eighteenth century were producing some important translations of Dutch editions of Western anatomical and medical works.

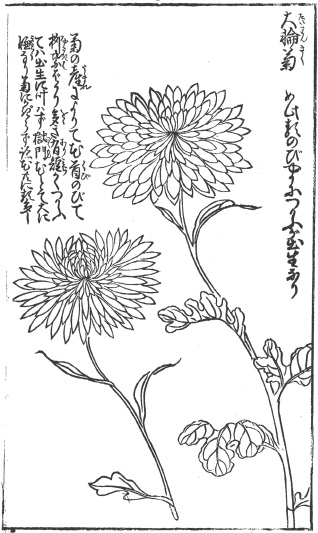

Figure 8.1

A page showing chrysanthemums from

Genji ikebana ki

(1765), a book of flower arrangements. Woodblock printing greatly facilitated the combination of illustrations and text on the same page, as here, and accounts for the very high proportion of illustrated books printed in Japan from the early seventeenth century onward.

By the early nineteenth century, Japan had a sophisticated publishing industry that covered the entire country through networks of retail booksellers and commercial lending libraries. Publishers catered even to niche markets; for example, with books on games and pastimes like Go, chess, and flower arrangement, or volumes on anatomy and mathematics: all required extensive illustration, which woodblock printing rendered easy to produce (

figure 8.1

). The mainstay of the industry, however, was illustrated fiction, which ranged from children’s texts consisting mostly of pictures, with dialogue squeezed in around the edges, to demanding historical novels enhanced by elegant calligraphy and illustrations by Hokusai and other famous printmakers. Most of the well-known names of the “floating world” print tradition were also in the business of producing book illustration. In many cases, they also created

ehon

, books consisting of nothing but pictures, mostly in black and white but, from the late eighteenth century onward, sometimes in color. The arts of the book in Japan reached their apogee in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when color printing using multiple blocks was combined with exquisite design sense to produce works like Utamaro’s book of insects,

Ehon mushi erami

(1788).

Another kind of publication to make use of color was maps, which customarily included not only cartographic representations but also pictorial elements and substantial amounts of text. From the middle of the seventeenth century onward, Japanese consumers had a considerable appetite for maps. Commercial maps of the main cities of Kyoto, Osaka, and Edo were issued annually; and large maps were produced by using series of woodblocks. Colored maps of Japan published from the late eighteenth century onward contributed to a sense of national identity and, by including lines of latitude and longitude, to a consciousness of Japan’s place in the larger world. By the 1850s, maps of Kobe and Yokohama were showing signs of a growing Western presence in Japan in the form of ships, consulates, and warehouses.

The economics of the book trade in the Edo period are obscure. Archival material is scarce and we have little information on print runs. It is usually estimated that, depending on the kind of wood used, no more than 8,000 to 10,000 copies could be printed from a set of printing blocks before the text became too poor in quality to be commercially marketable. At that point, the only option was to produce a new set of blocks: careful comparison of surviving copies indicates that this was not an uncommon practice by the nineteenth century, suggesting that some books were selling in tens of thousands of copies.

Authorship was now becoming a profession.

Ex gratia

payments to authors were sometimes made by grateful publishers even in the seventeenth century, but later writers became saleable commodities in their own right and publishers would trade on literary celebrities in publicity and advertising material. However, although a living could be made from writing fiction, copyright was held by publishers; authors enjoyed no intellectual property rights whatsoever.

A crucial financial consideration in the nineteenth century, when publishing larger and more expensive works of fiction, was the readiness of the commercial lending libraries to purchase copies. Commercial book-lending was practiced from the 1660s onward, but by the early nineteenth century there were more than five hundred commercial lending libraries in Edo alone, and many more scattered throughout the provinces, so that their purchasing power had an appreciable impact on profitability. Most of them specialized in current fiction, but many also stocked nonfiction, such as topographical works. The largest of them all, Daisô of Nagoya, had a stock in excess of 20,000 titles, ranging from sinology to light fiction.

Although commercial typography had come to an end in the 1650s, wooden movable type had been used occasionally by private printers thereafter. In 1848, however, a printing press and founts of Dutch type reached the Dutch East India Company outpost in Nagasaki, and they were purchased the same year by Motoki Shôzô, a government interpreter. In 1851–2 he used them, together with some

kana

type he had cast in Japan, to print a basic Dutch–Japanese dictionary. Under his direction, the government office in Nagasaki began printing some Dutch books for the benefit of Japanese scholars, and in the late 1850s and 1860s there were further experiments with imported presses to print books in Dutch, English, and Japanese. In 1854–5, the first treaties opening Japan to limited contact with Western countries had been signed and the number of resident foreigners began to grow, leading in 1861 to the

Nagasaki Shipping List and Advertiser

, the first newspaper published in Japan, albeit intended solely for the expatriate community. During the Edo period the thirst for news had been satisfied by occasional broadsheets known as

kawaraban

, which gave details of sensational events such as natural disasters, murders, and love suicides.