A Companion to the History of the Book (22 page)

Read A Companion to the History of the Book Online

Authors: Simon Eliot,Jonathan Rose

In 1868, the new Meiji government immediately began to put its stamp on the publishing industry. On the positive side, a government gazette was issued for the first time, giving the text of official decrees, but simultaneously the first steps were taken to impose a more effective system of prepublication censorship. In the 1870s, the regulations became ever more stringent in response to political opposition to the government’s authoritarian tendencies, and in 1875 the Libel Law stipulated that matters that reflected badly on government ministers and officials could not be reported even if true. From this point up to 1945, censorship became increasingly severe in application and punitive efficacy.

Although private and commercial libraries had long existed in Japan, travelers such as Fukuzawa Yukichi, who visited the West in the 1860s, perceived Western libraries as something different, emphasizing that they were open to all free of charge. The first such institution established in Japan was the Shojakkan created by the Ministry of Education in 1872, but in 1885 it started charging fees, thus differing from earlier commercial lending libraries only in the fact that provision was made by the state. It was in 1872, too, that commercial lending libraries adapted their stocks to the new shibboleths of the day and undertook to provide newspapers and foreign books on professional or scientific subjects, but many of them continued to stock the fiction of the 1830s. The publication in the 1880s of typographic editions of old favorites indicates that reading tastes had not surrendered completely to the lure of the West.

For the first twenty years of the Meiji period (1868–1912) woodblock printing remained the dominant technology, but thereafter the tide turned irrevocably in favor of movable type. The government had early on committed itself to typography, establishing in the Ministry of Works a bureau charged with casting type for the presses of central and local government agencies and of the newly founded Imperial University in Tokyo. This official encouragement had the greatest impact at first on newspapers. The first daily,

Kankyo Yokohama Shinbun

, founded in 1870, was printed for the first few years with wooden type, but in 1873 it adopted metal type. In the late 1870s and 1880s, movable type was increasingly used for book publication too, especially translations of Western books and new works of fiction.

New publishers, such as Hakubunkan (1887–1947), now came to the fore. Hakubunkan made its name with innovative journals and magazines, such as

Nihon Taika Ronshû

(Essays by Great Writers of Japan, from 1887), which carried articles by well-known contemporaries on issues ranging from medicine and hygiene to literature and education;

Nisshin sensô jikki

(True Account of the Sino-Japanese War, from 1894), which was the first photo magazine and carried pictures of the war; and

Taiyô

(The Sun, from 1895), the most popular general magazine. At the same time, it was undertaking bold publishing projects, such as a multivolume encyclopedia in 1889, and from 1893 the hundred-volume series

Teikoku Bunko

(Imperial Library), which reprinted literary favorites of the Edo period that had hitherto circulated either as woodblock books or as manuscripts. By the 1890s, very few of the old publishing companies, some of which went back to the seventeenth century, were still in business. Their place had been taken by new companies like Hakubunkan, which relied on typography, steam-driven technology, and new business methods.

In the twentieth century, leaving aside technological developments that were by no means unique to Japan, the most striking features of the publishing business were the vigor of the periodicals market and the continuing appetite for new titles. Of the many new periodicals, the most influential were

Chûô Kôron

(Central Review) and

Bungei Shunjû

(Literary Times), while the launch in 1903 of

Katei no tomo

(The Family’s Friend) and in 1917 of

Shufu no tomo

(The Housewife’s Friend) inaugurated long-lasting, mass-market magazines aimed at women readers. From the outbreak of war with China in 1937 onward, stringent controls were applied to periodicals and many were forced to close down. Immediately after the end of World War II, a number of new magazines were launched which took advantage of the end of wartime censorship to adopt a more liberal stance or to look to the West for fashions and lifestyle information. In successive decades, new launches established

Shônen janpu

(1968), a comic magazine for boys which reached a circulation of 6.5 million in 1993;

an-an

(1970), a very successful fashion magazine; and

Focus

(1981), a photo magazine that often carried sensational news items.

Manga

, or comics, have in postwar Japan constituted a large proportion of both magazine and book consumption. They have sometimes been criticized for violence, racism, or sexism, but they remain a visibly popular form of entertainment that is now closely tied to

anime

, or the Japanese animation film.

Over the past ten years, sales of new books have been in decline both in terms of numbers of copies and of net value, and the number of bookshops has also been falling, although it is still above 8,000 for the whole of Japan. The number of new titles published each year defies the downward trend and continues to rise, reaching 74,000 in 2002. Although an overwhelming proportion of the books published in Japan were originally written in Japanese, publishing globalization is demonstrated by the fact that the first printing of the Japanese translation of J. K. Rowling’s

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire

was 2.3 million copies. On the other hand, the globalization of Japanese books, as measured by the number of translations of Japanese books into foreign languages and by the number of copies of translations sold, remains at a low level, even in the English-speaking world. While the Japanese classics and the best of current fiction are now available in most European languages, it remains rare for academic, political, and other books to appear in English translation.

Korea

Korea is remarkable as the source both of what is considered by many to be the oldest datable printed item in the world (before 751) and of the oldest extant sample of typography, nearly a hundred years before Gutenberg. Both these texts are in Chinese, for, like Japan and Vietnam, Korea had no writing system before its encounter with Chinese characters and the written traditions of Buddhism and Confucianism. Hence Koreans, until the development in the fifteenth century of an alphabetic script for writing Korean, were constrained to write in Chinese. Their oldest surviving texts are Chinese translations of Buddhist sutras, which were copied in Korea in the eighth century. Chinese remained the written language of intellectual discourse until the twentieth century, but under King Sejong in the middle of the fifteenth century a phonetic alphabet was devised for writing the highly inflected Korean language; this script is now called

hangul

. Today, Korean is written exclusively with

hangul

in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) in the north, while in the Republic of Korea (ROK) in the south Chinese characters continue to be used for words of Chinese origin, although newspapers increasingly use

hangul

for them as well.

By the seventh century at least, woodblock printing was practiced in China, and the technology was transmitted, before the eighth century was over, to both Korea and Japan. In 1966, a printed Buddhist invocation in Chinese was discovered in a pagoda, constructed in 751, in the Bulguksa temple in Gyeongju; the date has been challenged and it has also been suggested that the invocation may have been printed in China. However, the paper is indubitably Korean and the consensus is that it was printed in Korea more than a dozen years before similar Buddhist invocations were printed in quantity in Japan. If printing was then practiced in Japan, it is

a priori

likely that it was also practiced in Korea, which was technologically ahead of Japan. In both countries, however, this was printing for ritual purposes, not for reading; the same was true of a sutra printed with illustrations in 1007, which was produced for inserting into a reliquary.

Thereafter, woodblock printing was put to more practical uses to produce Buddhist texts for study and devotion. The most ambitious undertaking was the production of a Korean edition of the vast Buddhist canon, inspired by the Chinese printed edition of 983, of which a copy reached Korea by royal request in 991. The carving of the blocks for the 6,000 volumes of the Korean edition began in 1010, but they were later destroyed during the Mongol invasion of 1232; no complete copy survives, but substantial parts are preserved in Japan. In 1236–51, however, the blocks for a second edition were cut, and more than 80,000 of these are preserved to this day in the Haeinsa temple in southern Korea. This edition of the canon, containing 1,516 texts in 6,815 volumes, was a more comprehensive collection of sutras and exegetical writings than anything previously produced in China or elsewhere, and was much sought after in Japan and the Ryûkyû kingdom.

The tradition of woodblock printing was joined in the twelfth century by typography. Movable type had been invented in China in the eleventh century, but it was put to much more extensive use in Korea. The oldest extant book in the world printed with metal movable type is a book written in Chinese by a Korean Buddhist monk, which was printed in Korea in 1377 and is preserved in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. There is, however, reliable documentary evidence of typographic printing in the early thirteenth century, and a twelfth-century matrix for casting type has recently been unearthed, taking the origins of Korean typography back even further. In 1392, the Korean court established the Seojeogweon, a printing office for casting type and publishing books, but it was in 1403, after the foundation of the Yi dynasty (1392–1910), that King Taejong declared his intention of harnessing typography for the benefit of the state: “In order to govern the country well, it is essential that books be read widely … It is my desire to cast copper [bronze] type so that we can print as many books as possible and have them made available widely. This will truly bring infinite benefit to us” (Lee 1993: 537). In the course of the fifteenth century alone, new sets of type were cast at least twenty-one times to print mostly Chinese works but also, for example,

Dongguk jeong’un

(1448), a guide to the Korean pronunciation of Chinese characters. By this time, wooden type was being used as well as metal type, and after the Japanese invasions of the 1590s, which left Korea deprived of its founts of metal type, wooden type predominated for half a century.

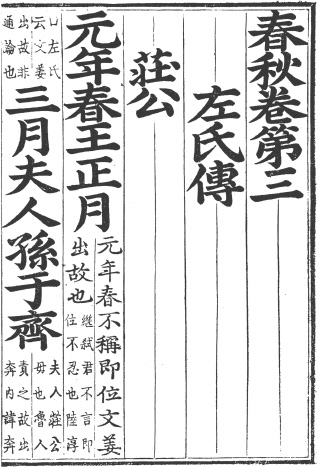

Thus, until the early twentieth century, Korean printers made use of a wide range of technologies in parallel: typography utilizing bronze, ferrous, or wooden type; woodblock printing; and a hybrid technology whereby different elements on the same page were printed using typography or woodblocks. The best example of the last is the 1797 edition of

Chunchu jwa ssi jeon

, which is the Korean name of the Chinese text called

Zuo’s Commentaries on the Spring and Autumn Annals

: on each page, the text of the

Annals

was printed in large size with woodblocks, while both the commentary in half size and notes by Korean editors in quarter size were printed with type cast in 1777 (

figure 8.2

).

These various technologies were used to produce five different types of book: Chinese volumes of Chinese authorship, such as the Confucian canon, which dominated education and intellectual life and which therefore constituted a high proportion of books printed; books written by Korean authors in Chinese, such as the

Samguk Sagi

(1145), a history of the three kingdoms of early Korea, the many works of the greatest Confucian scholar of Korea, Yi Toegye (1501–70), and even fictional works; books in Korean, which were fewer in quantity and often consisted of commercial editions of works of popular fiction; hybrid books, such as

Hyogyeong eonhae

, an early eighteenth-century Korean edition of the Chinese

Classic of Filial Piety

, which is furnished with

hangul

glosses and Korean translations; and maps. For maps obviously, and for books in Korean and hybrid books, woodblocks were the customary technology, although it is true that

hangul

type was cast for printing Korean from 1447 onward. For books in Chinese, typography was as likely to be used as woodblocks. In spite of the association between typography and government printing, it is important to note that even as late as 1909 some official publications were produced from woodblocks.

Figure 8.2

A page from the 1797 edition of

Chunchu jwa ssi jeon.

The use of various printing technologies by no means spelled the end of manuscript traditions, however. Many works of Korean fiction circulated mainly in the form of manuscripts, such as the seventeenth-century

Nine Cloud Dream

, which survives in nineteenth-century woodblock editions and in numerous manuscripts. It was common also to make manuscript copies of printed books, for reasons of economy or sometimes because the original was scarce. Thus, the copy of an agricultural manual titled

Nongga chipsoeng

in the Asami Library was made in 1891 from the 1686 edition, even though in 1734 the king had ordered all provincial governments to print and distribute it; apparently that edition had become hard to find by the end of the nineteenth century.