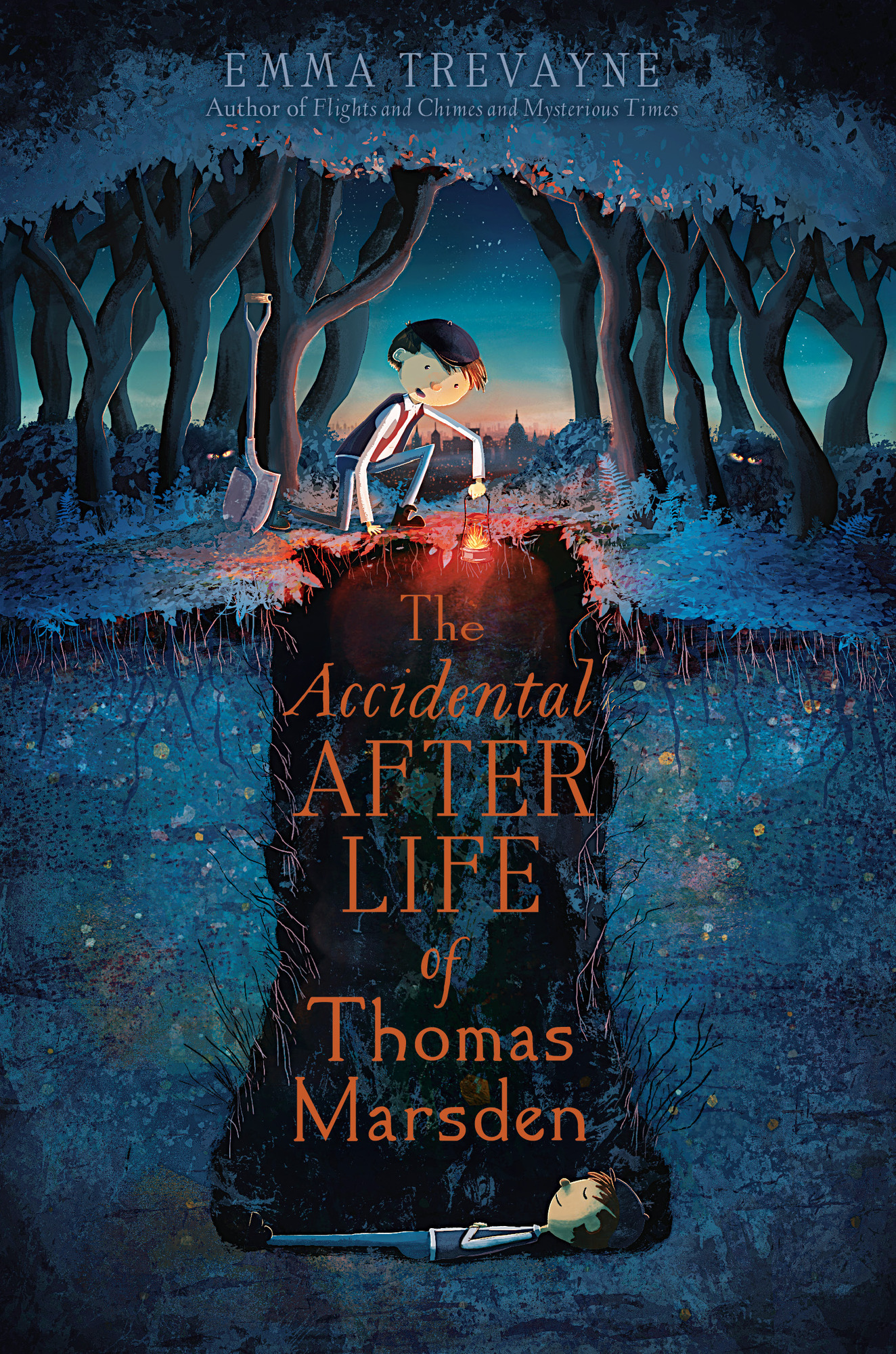

The Accidental Afterlife of Thomas Marsden

Read The Accidental Afterlife of Thomas Marsden Online

Authors: Emma Trevayne

THANKS

FOR DOWNLOADING THIS EBOOK!

We have SO many more books for kids in the in-beTWEEN age that we'd love to share with you! Sign up for our

IN THE MIDDLE books

newsletter and you'll receive news about other great books, exclusive excerpts, games, author interviews, and more!

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com/middle

To J. G. and A. R.,

with all the love and gratitude in this world or any other

And also with pineapples

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Different books grow from idea to novel in different ways.

Afterlife

was determined to surprise me at every turn; the only thing that never changed was its title. As much as I would like to claim I weathered those surprises through sheer force of will, in reality it was thanks to the support of the following people:

My family, particularly those who instilled a love of reading and words in me from such an early age.

Brooks Sherman. I could probably write books without the best agent ever, but I wouldn't want to.

Zareen Jaffery. For any author, an editor who just

gets

you and what you're trying to say is important. To have one who is also insightful, generous, understanding, brilliant, kind, and funny is a lottery win.

All the amazing people at Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, especially Mekisha for being awesomely organized when I'm not (which is most of the time), and Lizzy and Hilary for a beautiful book.

Glenn Thomas, who once again turned my words into stunning visual art.

A novel's worth of lovely, hilarious, strange-in-awesome-ways characters who are as essential to my success as the

faeries are to Mordecai's: Heidi Schulz, Stefan Bachmann, Claire Legrand, Katherine Catmull, and Alice Viccajee. Leiah, for keeping me supplied with sugar. My Strings, who know who they are.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, you. You who are holding this book and giving up your precious time to read it, you who may have read about weird music or magic birds and agreed to join me on another dark adventure. Thank you.

CHAPTER ONE

Bones

T

HOMAS MARSDEN WAS ELEVEN YEARS

old when he dug up his own grave.

It was the twenty-ninth day of April, though for only another few moments, and thus he would be eleven years old for only another few moments. When he awoke next morning, there'd be a tiny honey cake beside his bowl of gruel, and he'd give himself one bite each day until it was gone. The previous year, he'd managed to make it last near a week.

Midnight was clear and bright, with a hint of summer in the spring, and the headstones glowed like a mouthful of teeth under the moon. This was a messy business in the rain, so at least there was that. Thomas's fingers curled

around the shovel's handle as he looked back and forth across the plots, waiting for one to speak to him, just as he'd been taught.

When he was smaller, it'd been Thomas's job to keep watch, eyes and ears peeled for anyone who might have it in mind to stop them. There'd been some close ones, but nobody'd ever caught them.

But for a while now, Thomas'd been old enough to dig.

Behind him, his father waited. Waited to see if Thomas “had the bones.” That's what Silas Marsden called it, the sense of knowing which grave might hold the plunder that would feed them, keep the tallow candles burning another while.

The yew trees cast shadows of tall, dark ghosts waving gnarled arms and shaking wild, leafy heads. Stars peered through, bright, watching eyes, blinking in horror at the desecration that was about to come.

But stars knew nothing of empty bellies and grates with no coal. Stars always had fire.

“Hurry up, then,” grizzled Silas. “Find your bones, or I will.”

That wouldn't do. Silas was always just a bit more generous when Thomas did the workâand happier to have someone else to blame if they caught a dud.

Thomas turned this way and that, and froze.

“D'you hear something?” he asked. Footsteps, he was

almost sure of it. The very particular sound of footsteps trying not to make any noise.

Tap, tap, tap,

on the soft grass between the graves.

“Don't 'ear nothing. If I didn't know better, I'd think you was frightened. Not frightened, are you, son?”

Thomas straightened his shoulders. He most certainly was

not

. Perhaps it was nothing. Trees or an animal. He never felt alone in graveyards, anyway.

“This way,” he said, starting in the opposite direction from whence the possibly imagined footsteps had gone. Shovels over shoulders, they trudged along the paths, sacks in their hands, which would hopefully soon be filled.

Beyond the graveyard walls, the lively, stinking city felt very far away, banished by this land of the dead. Thomas dropped his sack and shovel beside a crumbling stone on which he could just make out the name

COSGROVE

because Mam had insisted he learn his letters.

In this work, there was always a choice to be made. Older graves might've been turned over already, their treasures taken, but for those as were untouched, what they held could be worth a whole handful of coin. Newer ones were a safe bet for a few bits and bobs, but rare was the one that'd feed them for a month.

The digging itself was no easy job. Sweaty and back-breaking and endless, the blades of the shovels

chewing up the earth and diving in for another mouthful, only to spit it out onto a growing hill beside the growing hole. When their arms would no longer reachâsooner for Thomas than his fatherâThomas would jump lightly into the grave and try not to think of what was beneath his feet.

And then there was a moment, there was always a moment, when metal struck wood and Thomas could loosen his blistered fingers from the handle, for they were almost finished. This was also the moment when the stench began to waft, a smell of sickness and decay. Thomas covered his nose with a ragged shirtsleeve that, truth be told, didn't smell much better.

Rotted wood splintered under a final blow, and again when Silas climbed down to pull the coffin's lid free of its rusted hinges.

“Not bad,” he muttered. “Not so bad at all. This'll fetch a bit from the right buyer if it's polished up right nice.” A silver brush, its bristles long since fallen away to dust, gleamed in his hand. Thomas tried quite hard not to look at the spot it had come from, right between two hands that were nothing but bone now, but he could never resist completely.

The whole body was nothing but bone, bone and gaps for mouth and nose, ears and eyes. Two silver coins had fallen with unheard

clunks

to the wood below at some point after it had been buried and forgotten.

“Reckon you can keep one of those,” said Thomas's father, as was his way. He was not, by and large, a cruel man, and always gave Thomas a small share of the spoils if Thomas helped. A bigger share, if Thomas chose, and chose well. Most times, Thomas slipped it into his mother's purse so she might return from market with a few extra morsels.

The brush, a music box, the other coin, and a pair of shoe buckles went into a sack. Not bad for a night. Thomas climbed from the grave, his father behind, and they made quick work of filling it back up from the mountain of earth. Oh, by the light of day it would be clear that someone had disturbed the plot, but by then they would be long gone.

“Got time for another.” The moon still shone high in the sky.

Soon they wouldn't, as the days grew longer and warmer and stole the darkness that shrouded them. Winter was best. They scarcely had to wait past suppertime, but on those bitter cold days when the ground was frozen solid, it oftentimes took a whole night to dig just one.

Thomas led them deeper into the graveyard, almost to the wall that surrounded it, and near clapped with glee. A fresh one, so new as to not even have a marker yet, no name to read or years at which to wonder. The digging was so much easier when they was fresh, too, the earth loose and unsettled, welcoming the body back into its embrace.

“An easy one, eh? Good job.” Thomas's father patted his shoulder with a calloused hand. The objects in the sack clattered together as it hit the ground, and they both readied their shovels.

They did not have to dig far.

And there was no wood to splinter.

A scant few feet down, Thomas's shovel struck something that was surely not a coffin.

“What in blazesâ? Careful!”

Thomas dropped to his knees and began to brush the earth away with his hands. The corpse was new, plump and cool, the cloth that covered it whole and perfect. Worms and critters hadn't gotten to it yet.

He swept the last of the dirt from the face, and his blood ran colder than the skin under his fingers. And then, as if it would make some sort of difference, he scooped the earth from the rest of the body in great, messy handfuls. It made no difference at all, no good one, and a dozen feelings all choked in Thomas's throat like a chicken bone, for looking at the body was like . . . like staring into a pond on a clear day.

When Silas Marsden had told Thomas to “find his bones,” this was not what was meant, but it might as well have been. In the grave, smeared with earth on skin not covered by a black robe, was Thomas himself, down to the ragged fingernails, the blemish on his cheek, there in

a shard of looking glass since Thomas could remember.

Silas Marsden whispered a prayer.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

There was not a single difference, so far as Thomas could see. True, he was not covered in earth, and his skin was warmer than the soil-smeared face below him, but those things weren't as important as the ones that were exactly the same. The face, the hands, the skinny chest when Silas parted the robe with the end of his shovel. Despite the strangeness before them, it seemed he couldn't resist the urge to make sure there was nothing of value under the cloth.

“I don't understand,” said Thomas. “It looks just like me. Why does it look just like me?”

“We bury it again,” snapped his father, ignoring Thomas's question, seeming to answer a different one as he looked up at the stars. “Doesn't have nothing to take. We bury it again and get out of 'ere. Come on, quick.”

“Butâ”

“Do as I say, or feel the back of my hand, boy!”

“But it does have something!” said Thomas, startled. Silas had never struck him, not when he spilled his supper or broke a mug or put holes in his jumpers, and he knew many who were not so fortunate. Silas was

afraid

, a thing so unfamiliar to Thomas it took him a heartbeat to see it for what it was.

But he couldn't do as Silas asked, for Silas was wrong.

Thomas pulled free the curl of paper from under the cold fingers that were otherwise identical to his own, and a shiver passed through him, as, briefly, he held his own hand.

Silas peered at it in the moonlight. “What's it say? Read those letters your mam's made you learn. Never saw any call for that, meself.”

The ink was so blue it was almost black, formed into whorls and spikes. At first look, they seemed nothing like the letters Mam had painstakingly taught him, sounding each one out and stringing them together into words. He squinted as the shapes seemed to wriggle and change.

“It says,

My name is Thistle,

” Thomas whispered. What an odd name. And what an odd feeling it was that came over Thomas, a wave of despair and fright from the boy at his feet, as clear as if the boy could talk and had whispered to Thomas that he was sad and afraid. Odd. But there was nothing about this that wasn't odd, and the name wasn't the only thing the note said.

Do not read this aloud. Go. Wear a cap. Watch. Speak to no one. This is essential.

Three more bits of paper had fallen to the ground. Thomas gathered them up, and these were printed in ordinary letters. He'd seen something like them once before, when the graves had been particularly rich and Mam had taken him to a penny theater as a treat.

Those tickets hadn't been made of such thick card, however, with gold leaf around the edges. The theater hadn't been in such a posh part of town as the address on these, neither.

The performance was the following night.

“This is all some daft trick,” said Silas, gripping his shovel tighter, the distraction over. “Get to work.”

Thomas slipped the note and the tickets into his pocket.

Calluses burned on Thomas's palm. He tipped the first load of earth slowly back into the hole, where it covered the face so like his own. Another shovel of dirt, slowly again. But his pace did not matter, for Silas Marsden worked as if possessed, scooping up huge clumps and throwing them into the grave, breath labored and loud in the quiet night.

He did not say another word to Thomas, not when they had finished, nor on the long trudge home, nor when he pushed open the creaking door and pointed in the direction of Thomas's small bed, really no more than a pile of moth-eaten blankets near the hearth.

If there was coal, Mam always left a few embers glowing for the bit of warmth that stole over Thomas as he climbed under the topmost blanketâthe thinnest and most threadbare. The others formed a nest underneath him that softened the hard floor. Most nights he was weary, tired to his very bones from hours in the graveyards, and grateful to

fall asleep soon as he was burrowed in, but not this night.

Tonight his bones in this bed couldn't be as tired as his bones in the grave, so exhausted they would never move again.

It simply made no sense, not the slightest bit. The Robertsons down the road and round the corner, they had two girls, twins, who looked so much the same that Thomas couldn't tell which was waving to him in the street. But Mam and Papa had never so much as hinted at Thomas having a brother. He longed to ask his father, longed right up until the moment Silas Marsden finished hanging up coats and shovels on the nails by the door and stomped across the room in socks badly in need of darning. The door to the house's one other room slammed shut hard enough to wake Mam, asleep on the other side.

Sure enough, voices slipped like smoke through the cracks around the wood. Whispers, and they got no louder even when Thomas crept from his bed to press his ear against the rough, splintery planks. The floor was cold under his toes, drafts breathed across his neck, but Thomas did not move except to sit when his legs would no longer hold him.

When Thomas woke, he was in his bed, warm, the fire ablaze in the hearth. A long spoon clanged on the side of a metal pot hung over the flames on a hook.

“Wake up. That's your breakfast ready,” said Thomas's mother. “Come now, eat.” She looked tired, great dark

circles under her eyes, but she was smiling as always. Her hair curled in wisps over her shawl.

“In the graveyardâ” Thomas began, remembering.

“There's clean water. Wash your hands, as I can guess you didn't before bed, and I won't have you getting my spoons mucky. Those as has an 'undred of them can get them as filthy as they likes, but not in this home, I say.”