A Companion to the History of the Book (51 page)

Read A Companion to the History of the Book Online

Authors: Simon Eliot,Jonathan Rose

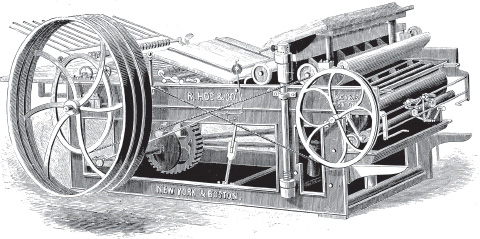

Figure 20.4

Hoe’s bed-and-platen book-printing machine. From

Typographic Messenger,

July 1867 (St. Bride negative 442).

Stereotyping and Electrotyping

Stereotyping is the method of creating a cast-metal printing plate using a mold taken from a form of type (or from a woodblock illustration). There are a number of reasons why it might have been desirable for book printers to use stereotyping, all of which have to do with saving time, money, or both. A printer who used stereotyping would not need to replace his type as often because it would not suffer as much wear and tear. It also meant that printers did not need to stock so much type, thus cutting down on what was otherwise an expensive investment.

The main advantage of stereotyping was the ability to reprint something at a later date without having to pay composition costs a second time. Paper was an expensive commodity and therefore not many printers (or publishers) could afford to print more copies of something than it was estimated that they could initially sell. Unfortunately, this meant that they might miss out on sales if they happened to underestimate the number of copies required. If there were sufficient demand for more copies of a particular title, the printer would have to undertake another print run. This required starting the job again from scratch and incurring for a second time all the costs that this entailed. This problem could be solved by leaving all the forms for a particular title standing. However, most printers would not have had large enough stocks of type to set a whole book and at any rate this was only practical for books that were in more or less constant demand. Stereotyping meant that reprints could be produced without expending further time and money to compose the pages afresh and without having to leave the type standing.

Stereotyping using casts made in sand or plaster had been in use since the 1700s, and the technique of “dabbing” to make stereotype copies of woodcuts and wood-engravings had probably been around for even longer (Mosley 1993). However, a reliable means of stereotyping forms of type was not in place until a method of casting plates from plaster of Paris molds was patented in 1784 by Alexander Tilloch, editor of

Philosophical Magazine

and part-proprietor of

The Star,

and printer Andrew Foulis. Their invention did not really take off until Earl Stanhope approached them in 1800 wanting to develop and use their process. In 1803, a printer named Wilson, under the patronage of Stanhope, set up as a stereotype printer. Both Cambridge University Press and Oxford University Press soon had agreements with Wilson for the printing of Bibles, Testaments, and prayer-books.

Casting stereos using plaster of Paris was expensive and time-consuming. It required specially cast type and took around two hours to make a single plate, not including the time it took to bake the mold. The protracted nature of the process was exacerbated by the fact that each mold could only be used to make one plate because it was always destroyed during casting.

Around 1828–9 the papier mâché method of casting stereotype plates was rediscovered (having previously been used as early as the seventeenth century) by Claude Genoux in France. This superseded Stanhope’s method and continued to be used, more or less unchanged, until the use of metal type for commercial printing came to an end. Genoux’s process replaced plaster of Paris with papier mâché or “flong.” The wet flong was laid on top of the form and beaten with a stiff brush to force it into the gaps. It was then removed and dried, ready to be used for casting plates. A special “drying and casting press” was used to dry the mold, initially while it was still pressed against the form. The same piece of equipment was used to cast the plates: the press was moved from a horizontal to a vertical position, which allowed the air to escape when metal was poured in. The flong, or wet-mat, process was much faster than the Stanhope process and did not require special type. Most importantly, the flong molds were not destroyed in casting, meaning that they could be used repeatedly and also that they could be stored for possible future use without having to undertake the actual casting of plates, thus saving time, money, and storage space. The molds could also be packaged and transported safely so that they could be made in one place and the plates cast and printed elsewhere. The flong molds were soft and pliable and so could be curved into a hemispherical shape and then used to cast curved plates for use with rotary presses.

The spread of stereotyping early in the nineteenth century generated an explosion in the number of “stock blocks” that were available from type-foundries; some companies traded in nothing but stereotype blocks. This meant that printers now had access to cheap images to enliven their printed pages, a system similar to the picture libraries of today.

From the late 1830s, electrotyping was also used for plate-making, especially for the duplication of wood-engraved blocks. A mold was made using wax or plastic and a thin layer of metal was deposited on the mold using electrolysis. The resulting “shell” was an exact copy of the original, faithfully reproducing even the finest lines. This had to be strengthened, by backing with a lead alloy, and then mounted onto a block of wood before it could be used for printing.

Bookbinding

In 1800, books were still bound by hand, usually after being sold to the bookseller or private individual as flat sheets or in paper-covered boards which were not intended to be durable. By the end of the century, all the various aspects of bookbinding had been mechanized and most books were sold ready bound. The first machine to enter the bookbinding trade was the rolling press which was used to flatten the folded sheets before binding:

a process that had hitherto been performed by a workman hammering the sheets with a fourteen-pound beating hammer – a monotonous job concerning which Arnett gave this warning: “When employed at the beating stone the workman should keep his legs together to avoid hernia, to which he is much exposed if, with the intention of being more at ease, he contracts the habit of placing them apart.” (Darley 1959: 29–30)

By 1830, the rolling press was in use at most binderies, but the folding of printed sheets and binding of books continued to be done by hand well into the nineteenth century. As in other areas, it was the newspaper trade that led the way: the first folding machines were in use by the 1850s, attached to cylinder presses for folding newspapers as they were printed. By the end of the century, machines to fold sheets for binding into books were in use, and paper-cutting, gathering, stitching, stapling, and gluing were all automated. Mechanical means of attaching the covers and stamping the lettering on them had also been devised. In large binderies, all these machines were connected by a system of belts and pulleys to one or two steam engines that provided the power.

One of the most important developments was not a new machine but a new material. In 1820, Charles Pickering published the first of his “Diamond Classics” series (set in 4½ point “diamond” type) which were bound in cloth. In 1830, Pickering applied lettering to the spine of his cloth bindings using the new arming press – an iron printing press adapted for this purpose. The covers had to go into the arming press flat and this meant that they had to be made separately, so the lettering could be stamped on, before being glued to the book.

Shortly after this, it was discovered that even sewing could be dispensed with. The sections of a book were guillotined down the back, so that the book, instead of being, say, ten sections of thirty-two pages, became three hundred and twenty loose sheets of paper. By using a special kind of adhesive called caoutchouc, or gutta-percha, these pages could be made to adhere to the case quite satisfactorily. (McLean 1972: 6–7)

For reasons of economy, most books conformed to one of a number of standard sizes that related to the size of the paper that they were printed on. After the adoption of DIN (Deutsche Industrie Norm) paper sizes, books began to be printed in A4 and A5 formats, particularly after these sizes became common due to the spread of the photocopier after World War II.

Hot Metal

Preparing pages of metal type for printing was a time-consuming and expensive process, but it was not until the end of the nineteenth century that punch-cutting, type-casting, and composition were all automated, and all three continued to be done by hand well into the twentieth century. The first breakthrough came with the introduction of type-casting machines: David Bruce’s pivotal caster, invented in the US in 1838 and introduced to the UK in the middle of the nineteenth century, was capable of casting 6,000 pieces of type in an hour – around twelve times as many as a hand caster. Later machines improved output further, casting over 50,000 pieces of type an hour.

The slowest part of the process of manufacturing type by hand was punch-cutting – cutting a single punch and making a matrix from it could take a day or more. Punch-cutting was finally mechanized in 1885 with the invention of Linn Boyd Benton’s punch-cutting pantograph. This worked in a similar way to the pantograph for cutting wood type, but instead of making wood letters it made metal punches. The starting-point is a large drawing around 25 cm (10 inches) high. In cutting punches by hand, the only function of drawings is to provide a visual reference for the punch-cutter. In mechanized punch-cutting, drawings were an integral part of the system – for the first time in the history of type production the designing and making became separate parts of the process. The drawing was used to make a pattern, usually in metal, which the pantograph machine could trace around to produce punches in whatever size was required.

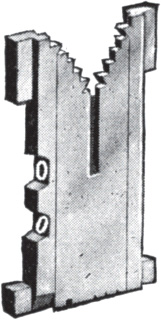

Figure 20.5

A double-letter Linotype matrix. From W. Atkins (ed.),

The Art and Practice of Printing,

1932.

A number of abortive attempts were made to mechanize the composition of type during the nineteenth century, which failed due to a combination of poor engineering and opposition from compositors. The answer was found at the end of the nineteenth century in the shape of machines which both cast and composed type. The first was the line-casting system introduced by Ottmar Mergenthaler in 1885 and developed subsequently by the Mergenthaler Linotype Company. The Linotype machine was first used by

The New York Tribune

newspaper. The machine carried a magazine of matrices similar to those used for hand-casting which were released by pressing keys on a keyboard to fall into a line. The operator then cast the whole line as a solid slug, a “line o’ type,” which gave the machine its name (figures

20.5

and

20.6

).

At the same time as Mergenthaler was developing his Linotype system, Tolbert Lanston was working on a rival machine called the Monotype which cast and composed individual pieces of type. Lanston’s machine had two parts, a keyboard and a caster. In the Monotype system, text was composed at a keyboard that punched character codes into a paper ribbon. The Monotype caster had all the matrices for a single typeface in a matrix case. The matrix case moved under instruction from the codes on the paper ribbon. Each character code in the paper ribbon produced at the keyboard was made up of two holes. At the caster, these controlled a pair of pins in the mechanism that positioned the matrix case over the mold. One pin selected a column of matrices in the case; the other a single matrix within the column. Because it cast and composed individual pieces of type, corrections could easily be made to typesetting done on a Monotype machine (

figure 20.7

).

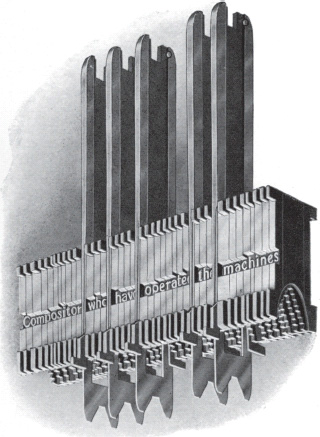

Figure 20.6

A line of single-letter Linotype matrices and spacebands, ready for casting a line of type. From L. A. Legros and J. C. Grant,

Typographical Printing-surfaces,

1916.