A Companion to the History of the Book (52 page)

Read A Companion to the History of the Book Online

Authors: Simon Eliot,Jonathan Rose

In the first half of the twentieth century, both Linotype and Monotype introduced many of their own typefaces which, now in digital form, remain the staples of book design today. The majority of these typefaces were historical revivals based on typefaces used by great printers of the past, such as Manutius, Plantin, Baskerville, and Bodoni. They also produced some entirely new types, the best known being Monotype’s Gill Sans and Times New Roman.

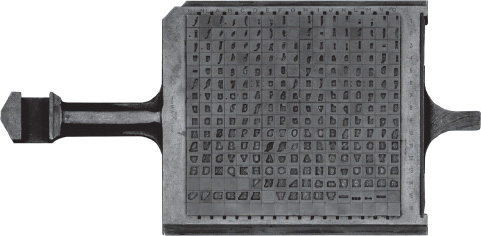

Figure 20.7

A Monotype matrix case. Department of Typography and Graphic Communication, University of Reading.

Lithography

Arguably one of the most important developments in the industrialization of the book was the invention of lithography by Alois Senefelder in Munich in 1798. Lithography was the first entirely new method of printing to have been invented for hundreds of years. The key to the process is the basic principle that grease and water do not mix. If marks are made on a flat, porous stone surface with a waxy crayon or other greasy substance it will stick to the stone and be partially absorbed. The whole surface can then be moistened and the water is attracted to the stone but repelled by the grease. If the stone is then inked up with greasy printing ink, the ink will adhere to the greasy marks but be repelled by the water. The ink can then be transferred to a sheet of paper through the application of pressure. Unlike relief printing where the printing surface is raised, or intaglio where the ink is contained in incised grooves in a metal plate, in lithography the printing surface is flat.

Soon after its invention, lithography was being used to print books, mostly very small in both extent and print-run, but for the most part it was used for jobbing work and the reproduction of works of art and had very little impact on the book trade. In many ways, letterpress printing was extremely restrictive: the nature of type made of small, rectangular blocks of metal imposed limits on what could easily be printed. Lithography, on the other hand, allowed a great deal of freedom: any mark that could be made on the stone could be printed and so it had a great advantage over letterpress when it came to printing tables, diagrams, music, equations, maps, and the like. It was also capable of reproducing handwriting and so enabled the printing of non-Latin languages without the need to invest in expensive typefaces that would rarely be used. However, lithography was much slower than letterpress, and while powered machines were developed for letterpress printing early in the nineteenth century, lithographic printing relied on the hand press until after 1850. This meant that lithography was only used for printing short runs of books in circumstances in which the most could be made of its flexibility.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, powered machines with automatic inking and damping mechanisms were introduced, but further development was hindered by the fact that the rotary principle could not be applied to lithographic stones. The answer was the development of offset printing and the introduction of metal plates to replace the lithographic stones. In offset printing, the ink is transferred from the lithographic stone or plate to an intermediate rubber cylinder and then on to the paper. In the first quarter of the twentieth century, both sheet- and web-fed rotary presses for offset lithographic printing were in use. However, the vast majority of books (and newspapers) continued to be printed by letterpress. In part this was due to the fact that lithography was thought to be inferior to letterpress in terms of clarity of impression and density of ink. Because lithography deposited less ink, the printed result often had a rather “flat” look compared with letterpress, where the ink was caused to spread by the enormous pressure of the press. The use of water in the process tended to grey the ink and cause a certain amount of paper distortion, with resultant problems in register. Lithography was also hindered by the fact that text had to be composed in metal first.

The original method was to set type by hand, proof it on special transfer paper, and then transfer the image to stone; later, type was set on a composing machine, proofed, and then photographed down onto a plate. But in both methods there was an initial stage when the text could just as well have been printed in an edition by letterpress. (Twyman 1970a: 29)

Letterpress printing finally began to be superseded by lithography in the 1960s when the advent of phototypesetting meant that text could be composed without using metal type (see below).

Although most books were originally printed by letterpress in the first half of the twentieth century, some were then reproduced using offset lithography – often when US and UK publishers collaborated on a title. The normal procedure was to have the book printed and typeset in one country, then to send the other publisher printed sheets or a finished copy that could be photographed for printing by offset lithography. This would save around 50 percent of the cost of typesetting and was also a very quick way of working.

Color

After some experiments in the incunable period, it became unusual to find color in books because it was difficult to justify the added expense. After 1800, color printing became more widespread, mainly driven by the demands of the advertising industry, but there was also an increase in the use of color in books. Text printed in color was generally limited to the occasional two-color title page, although there were exceptions, such as the version of the New Testament produced by De la Rue and Giles Balne in 1829 which was printed throughout in gold on special porcelain-coated paper. Illustrations printed in color were much more common, although the vast majority were still in black only. The best-known developments in this area are probably those of Savage, Baxter, and Knight, in the first half of the nineteenth century, although they were by no means the first to experiment with printing images in color.

William Savage’s book,

Practical Hints on Decorative Printing,

was published in two parts in 1818 and 1823. Savage used oil-less inks to print a series of wood-engraved blocks, each in a different color, to build up a full-color image.

The book is a virtuoso performance. One of the plates, “Ode to Mercy”, was printed from as many as twenty-nine different wood-blocks and is a masterpiece of technical skill if not in conception. Savage’s major contribution was to refine and extend the technique used by John Baptist Jackson in the eighteenth century by introducing rich colours and a great many more workings. (Twyman 1970a: 38)

Baxter’s method was similar to that used by Savage, using a series of woodblocks to print different colors in order to produce the effect of full color. Unlike Savage, Baxter used oil-based inks and an intaglio key plate for the black working, which was usually a complete picture in its own right.

Charles Knight’s career began at around the same time as that of Baxter. In 1832, he founded the

Penny Magazine

and this was followed by numerous books, often issued in parts, and all of these early works were illustrated with woodcuts. In 1838, Knight patented a method of color printing which he termed “illuminated printing.” Like Baxter, Knight used oil-based inks, although his process differed in that he printed the colors first, from metal plates, with the black added last from a woodblock. The key to his idea was to apply four colors to a single sheet during the course of a single pass through the press. The sheet of paper remained stationary in the press until all the colors had been applied. This was achieved by fitting the press with a revolving frame in the place of the usual platen. Each color was printed on top of the preceding one whilst the ink was still wet, meaning that further colors could be created by mixing the inks together. In the field of lithographic printing, Godefroy Engelmann in the 1830s pioneered a similar method, called chromolithography, of building up color images using different stones to print different colors. Chromolithographed illustrations were used in books, sometimes with spectacular results, as in Owen Jones’s masterpiece,

The Grammar of Ornament

(1856). All of these methods required the separation of the original into its constituent colored plates by eye, each plate then being engraved by hand. Later this was done using photography (see below).

Photography

The first role of photography in books was simply as tipped-in illustrations, one of the best-known early examples being the four-volume

Reports by the Juries

of the Great Exhibition in 1851, which contained 155 pasted-down photographs. From around 1860 photographic images were transferred onto wood blocks by sensitizing the surface of the block before being engraved by hand as before.

By the 1870s it was possible to use photography to reproduce line drawings or other images with no tonal values. The original was photographed and the negative exposed onto a metal plate coated with a light-sensitive emulsion that hardened where it was exposed to light.

Development removes the unexposed emulsion and leaves the drawing represented by lines of hardened emulsion on the surface of the bare metal. The plate is now treated to convert the emulsion into an acid resist, and it is then ready for etching. Etching with acid eats away the surface of the metal wherever it is unprotected, leaving the resist protected lines standing in relief. (Jennett 1967: 130)

However, paintings and photographs that had shades of grey could not be reproduced this way with black ink and white paper. The answer came in the shape of the halftone screen. “This was a device used to break down the tonal image of a photograph into a series of small dots. The size of the dots depended on the amount of light passing through a mesh of lines engraved on glass and on the coarseness of the mesh itself” (Twyman 1970a: 31). The negative was exposed onto the plate through this mesh of tiny holes (the “screen”) resulting in a “halftone” block broken up into raised dots of greater or smaller size in correlation to the light and dark areas of the photograph. The same principle is still used to reproduce images today. When printed, and viewed at reading distance, the dots appear to reproduce the tonal values of the original photograph. In crude halftone screens, with larger dots, the dot pattern can sometimes be seen with the naked eye, but usually the dots are so small that they can only be seen with a magnifying glass.

The same method was later applied to reproducing color photographs using three or four colors to give the effect of full color. The original is photographed through a red, a green, and a blue filter. The halftone plates made from these photographs are called color separations and are printed in cyan, magenta, and yellow respectively (in four-color printing black is added). The resulting printed image is actually composed of different-sized dots in these three colors, but the human eye is fooled into seeing a complete range of colors.

Halftones printed better on coated or “art” papers, which were not suitable for printing text by letterpress, and so most books featuring halftone reproductions had them printed on different paper from the text paper to form a discrete section of the book, usually at the back or in the center. As the quality of reproduction improved, more “integrated” books were produced where the text and halftones were placed together on the pages.

Metal plates for lithographic or offset lithographic printing could also be made photographically. A metal sheet coated with a light-sensitive substance that would also attract greasy printing ink was exposed to light through a negative film. The coating hardened in the parts hit by the light and the rest remained soft. The soft parts were washed out, leaving the metal plate bare in these areas. Finally, a water-receptive substance was applied which adhered only to the bare metal, leaving only the area to be printed receptive to ink.

In the early 1960s, a new technology, called photosetting or filmsetting, began to become a significant force. This was a means of setting type using photography, based on a very simple principle: by shining light through a photographic negative of a character, an image of that character could be made on photosensitive material. The character images were negatives carried on a matrix – transparent images on a black background. As with hot metal machines, there was a selection mechanism that responded to input from a keyboard, choosing and positioning the correct characters. However, instead of positioning the character over a jet of molten metal, it was positioned over a high-intensity light source and then exposed onto a photosensitive film or plate. Most phototypesetting systems also had a screen where the typesetter could see the text they had entered, allowing them to edit and correct it.

There were many different phototypesetting machines, some simple, some complex. In some, the different components were separate, others were combined into a single master unit. Typefaces for phototypesetting systems came in a variety of forms (discs, disc segments, film strips, and grids), which were not interchangeable between different systems. In some systems, the fount matrix remained stationary while the light source moved; in others, the matrix spun or rotated, while the light source remained stationary.

Phototypesetting allowed much greater freedom than metal type. Metal type was limited to a small number of different sizes and the space between the characters could be increased by set amounts but not decreased. With phototypesetting, characters of any size could be produced and the spacing between them altered as required. As with most new printing technology, there was initially some resistance to phototypesetting, but it was ideally suited to offset lithographic printing and together these two technologies offered a serious alternative to hot metal and letterpress printing. During the 1970s, phototypesetting became the predominant method of setting type.