A Companion to the History of the Book (79 page)

Read A Companion to the History of the Book Online

Authors: Simon Eliot,Jonathan Rose

32

The Importance of Ephemera

Martin Andrews

By its very definition, book history concentrates on the contents and artifact of the book. But to explore and understand the subject in all its dimensions, we need to extend beyond the book itself to consider a breadth of contextual issues. In addition to literary content and organization, we need to study topics such as printing and production; readership and the act of reading itself; the buying, selling, and distribution of books; the availability of, and discussion about, books, libraries, and literary societies. Printed ephemera can contribute to all of these areas of research, providing a rich and important source of information.

What objects do we mean when we refer to ephemera? Even in the particular area of ephemera relating to the book, the range is enormous: prospectuses, catalogues, billheads and letterheads, bookmarks, posters announcing publications and literary events, handbills for circulating libraries, booksellers’ labels, galley proofs, book tokens, dust jackets, advertisements – the list goes on. Individually, items of ephemera might seem trivial and peripheral, but cumulatively they can throw a very particular light on history, offering not only factual detail but also an atmospheric and evocative direct link with the past.

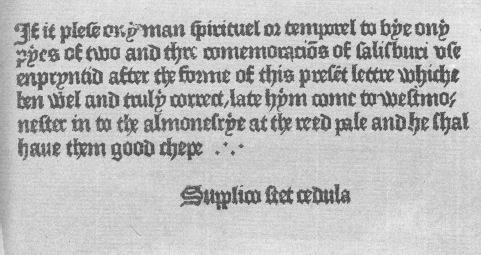

With the growth of literacy, communications, advertising, and marketing, there was a great proliferation of jobbing printing in the nineteenth century, but ephemera relating to the printing, publishing, and marketing of books have existed since the very beginning of printing with movable type. The first dated specimen of Western printing was not a book but a piece of ephemera: an indulgence probably printed by Johann Gutenberg or by his partners Fust and Schoeffer in 1454. Although rare, examples of ephemera from the earliest days of book printing have survived. Two copies of a short advertisement printed by William Caxton in about 1478 for his

Commemorations of Sarum Use

still exist (

figure 32.1

). The advertisement promises that the book is competitively priced (“good chepe”).

Occasionally, items such as a prospectus or advertisement are bound into a book or more commonly found hidden away in the binding. The value of paper was such that redundant items were reused as one of the layers of pasteboard or pasted down to the wooden board. This was possibly the fate of a list of books for sale printed by Peter Schoeffer in 1470. The list was used by a traveling salesman who wrote his address at the bottom of the sheet. The final line of the list is picked out in a larger size of type as a specimen of the typeface used in the Psalter for sale. In 1498, Aldus Manutius circulated a list of books printed in Greek, classified by subject (grammar, poetics, logic, philosophy, sacred scriptures), and priced. In America, ephemeral items such as broadsides were the stock-in-trade of the first printers. The first book published in the English colonies was the Bay Psalm Book of 1640, printed by Stephen Daye. But he is also known to have printed a “Freeman’s Oath” broadside and an almanac.

Figure 32.1

William Caxton’s advertisement for

Commemorations of Sarum Use,

c.1478. Reproduced from a photolithograph facsimile published in 1892. The original is in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

There have been many debates about a precise definition of printed ephemera, but there is much to be gained from a wide, embracing approach, accepting fuzzy edges. Broadly, the derivation of the word lies in the Greek

epi

(about or around) and

hemera

(a day). The word is also used as the specialist term for the freshwater insect, the mayfly

(Ephemera danica),

which, in its adult winged form, is commonly believed to live for only a day. For astronomers, astrologers, and navigators, the word

ephemeris

is used for a calendar or table of days. Even Dr. John Johnson, appointed printer to the University of Oxford in 1925 and founder of the extensive and celebrated collection of ephemera that is now housed in the Bodleian Library, found it difficult to be precise. He said his collection consisted of “common printed things … what is commonly thrown away – all the printed paraphernalia of our day-to-day lives, in size from the largest broadside to the humble calling card … from magnificent invitations to coronations of kings to the humblest of street literature sold for a penny or less.” On another occasion, he defined it as “everything which would normally go into the wastepaper basket after use, everything printed which is not actually a book” (Rickards 1988: 14). But Johnson’s definitions were not meant to be deprecating; on the contrary, he greatly valued ephemera as documentation of his world of printing and publishing: “I keep every trade card of every traveller who comes within the gates [at OUP], and treasure them in my archives. They are among the many gauges of our craft” (Johnson 1933: 46).

Today, there is wide recognition of ephemera as an important historical source. As Asa Briggs argues, “In the reconstruction of the past everything is grist to the historian’s mill, and what was thrown away is at least as useful as what was deliberately preserved. As our sense of past times changes, we try to strip away the intervening layers and discover the immediate witnesses” (quoted in Rickards 1988: 9). Ephemera provide us with a very particular kind of evidence. They offer an opportunity for scholarly analysis as well as a more subjective quality, an almost emotional and tactile response to worn and fingered material, directly handled by the people whose concerns and activities we are trying to understand, material that, against the odds, has survived and come down to us, often in a fragile state. In an unpublished essay, “The Study of Ephemera, 1977”, the ephemerist Maurice Rickards wrote:

An implicit component of every item of ephemera is the reader over our shoulder – the eyes for which the item first appeared; the living glance that scanned the paper even as we ourselves now scan it … Not only can you “hear their voices”, as Trevelyan put it, you can merge your glance with theirs … You become, as you read, an intimate part of the detail of their experience – not just overhearing them, but being momentarily

within

them … As we survey a battered public notice or a dog-eared printed paper, we are aware not only of the sum total of duration (implicit in its wear and tear), not only the buffetings and bruisings that its condition proclaims, but the countless scannings it has undergone – the multitude of readings and re-readings. It is, as you might say, “eye-worn” … (quoted in Rickards 1988: 16–17)

There are other areas of confusion and debate. One is the problem of distinguishing when a pamphlet, brochure, or other minor publication can be described as a book and therefore no longer ephemera. Librarians commonly define a book as being a bound work of thirty-two pages or more. Is a newspaper or magazine to be classed as ephemera? Such publications are given bibliographical status and are kept in libraries and yet are also thrown away after use. This clearly is an issue when looking at essays, serialized novels, and short stories in journals and popular magazines. Furthermore, the artifactual description of “book” is given to a variety of documents: order book, stamp book, autograph book, ration book, and specimen or sample book. Another issue is how to categorize letters and manuscripts. Is the daybook of the publisher Longmans to be considered ephemera compared with a hand-scribbled note from the publisher to the printers? However, precise and rigid definitions are unhelpful. What is important is how this huge and diverse area of material can inform a study of the history of the book.

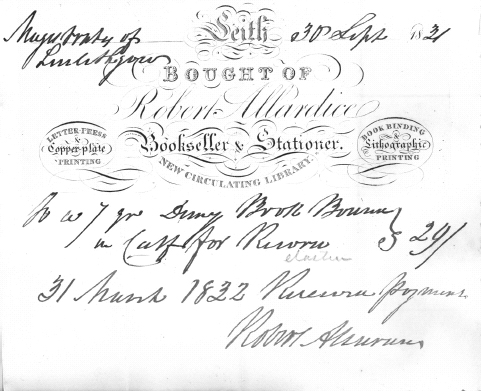

Figure 32.2

Receipt from Robert Allardice, bookseller and stationer, 1831- John Lewis Collection, Reading University Library.

Finding material is often a matter of chance, locating the odd relevant item in private collections of printed ephemera or among specialist traders or at regularly held ephemera fairs. But there are also major collections in libraries, museums, and company archives, such as the collection of typographer John Lewis at the University of Reading, organized with sections relating to bookselling, publishing, libraries, printing, and printers (

figure 32.2

). The seventeenth-century diarist Samuel Pepys had a particular passion for ballads, chapbooks, and other street literature, preserved in the Pepys Library at Magdalene College Cambridge. Amongst thousands of items that form “a throwaway conspectus of the life and times of a remarkable Londoner” (Rickards 1988: 39) are forty or so trade cards gathered from the businesses within walking distance of his home, including this card for a bookseller: “Roger Tucker. Bookseller at the Signe of the Golden Legg. At the corner of Salisbury Street in the Strand. Sells all sorts of Printed Books and all manner of Stationery Ware at reasonable Rates. Where aliso one may have ready mony for all Sorts of books.”

Another seventeenth-century collector of street ballads, John Bagford, was to become notorious as something of a vandal to those interested in books. Brought up as a shoemaker in London with little formal education, Bagford nevertheless gained a reputation as a bibliophile. He was commissioned as an agent by many distinguished book collectors and academics, including members of the Society of Antiquaries, to search out specific and often rare volumes for their libraries. Ferreting around in attics, cellars, street markets, and dusty bookshops in England and abroad gave him an opportunity to research his own book,

Proposals for Printing an Historical Account of that Most Universally Celebrated, as well as Useful Art of Typography

(1707). Unfortunately, to inform his study and provide illustrations, Bagford amassed a vast collection of title pages, frontispieces, and illustrations, which some believe he wantonly cut out of precious volumes – even destroying books for their bindings and endpapers. In

The Enemies of Books

(1888), William Blades described Bagford as a “wicked old biblioclast” who “went about the country from library to library tearing away title-pages . . .” (quoted in Rickards 1988: 44). Alongside his misdirected passion for books, Bagford was also fascinated by social history and picked up and preserved a vast cross-section of printed oddments of the time: tickets, bills, lottery puffs, price lists. Included in this mass of trivia was material relating more closely to his interest in printing and publishing: galley sheets, bookplates, specimens of paper and watermarks, and price lists. Bagford’s collections are now housed in the British Library.

From the very beginning of jobbing printing in America, certain collectors felt compelled to preserve the ephemeral scraps that accompanied their everyday lives, recognizing their worth as, in Dale Roylance’s words, a “persuasive graphic witness to their times” (1992: 6). Perhaps the greatest of these early collectors was Isaiah Thomas (1749–1831), founder of the American Antiquarian Society and a successful printer and publisher. In his early career, Thomas produced radical newspapers (the most famous being the

Massachusetts Spy)

and revolutionary patriotic rhetoric as a passionate supporter of the cause of American independence. After the war, Thomas concentrated on his business enterprises: settling in Worcester, Massachusetts, he eventually owned several printing offices, bookstores, paper mills, and a bindery. As well as books, he published newspapers, broadsheets, sheet music, periodicals, pamphlets, children’s literature of all kinds, and a yearly almanac. He retired at the age of 53 to dedicate himself to his interest in documenting the history of the young nation, and in 1810 published his book,

The History of Printing in America.

As the first librarian and president of the American Antiquarian Society, Thomas amassed a vast collection of printed ephemera, incorporating his own personal archives and also material he had purchased, such as a large proportion of the Mather family collection. In his account of the society, published in 1813, Thomas wrote: “We cannot obtain a knowledge of those who are to come after us, nor are we certain what will be the events of future times; as it is in our power, so it should be our duty, to bestow on posterity that which they cannot give to us, but which they may enlarge and improve and transmit to those who shall succeed them” (Thomas 1813: 4).