A Companion to the History of the Book (81 page)

Read A Companion to the History of the Book Online

Authors: Simon Eliot,Jonathan Rose

Reference has already been made to the problems involved in a precise definition of a book. This leads to the consideration of a range of published materials that are booklike but, because of their short length and bindings, are categorized as booklets or leaflets. Chapbooks, playbooks, and short monographs fall into this category. The dissemination of texts through these cheaper forms of publication could introduce a new readership to particular authors and lead on to book reading. The chapbook takes its name from the itinerant “chapman” or street vendor who sold these cheap and crudely printed booklets of anecdotes, romantic tales, verses, riddles, and puzzles. Usually of a small size (about 145 × 90 mm, from four to twenty-four pages), they were frequently sold unstitched and untrimmed, the reader having to finish off the binding at home. For many readers, chapbooks had the advantage over the broadsheet in that they more closely resembled a proper book. They often relied on worn and battered old type and woodcuts recycled from previous publications. The success of the chapbook led religious organizations to publish tracts and essays with a similar format but a higher moral tone. The texts of popular plays performed in nineteenth-century theaters were cheaply printed and sold as souvenirs. Single-section, stitched, paperbound textbooks of a more scholarly nature were also commonly available in the nineteenth century. Thomas Gray’s

Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard

and James Shirley’s

Death the Leveller

were published in Green’s “Scholastic Series of Poetry.” Extending to twelve pages and with extensive notes and biographical details, these little volumes sold for a penny.

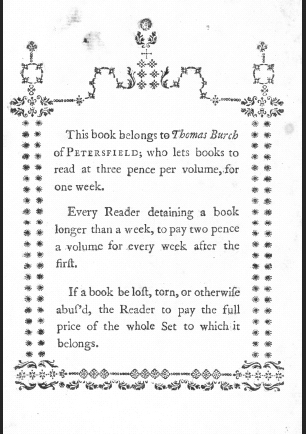

Figure 32.8

Bookplate, Thomas Burch of Petersfield, early nineteenth century. Maurice Rickards Collection, Centre for Ephemera Studies, Reading University

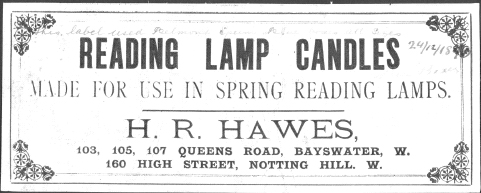

Other ephemera can provide a context for the reading and handling of books: for example, the packaging of candles used for illumination (

figure 32.10

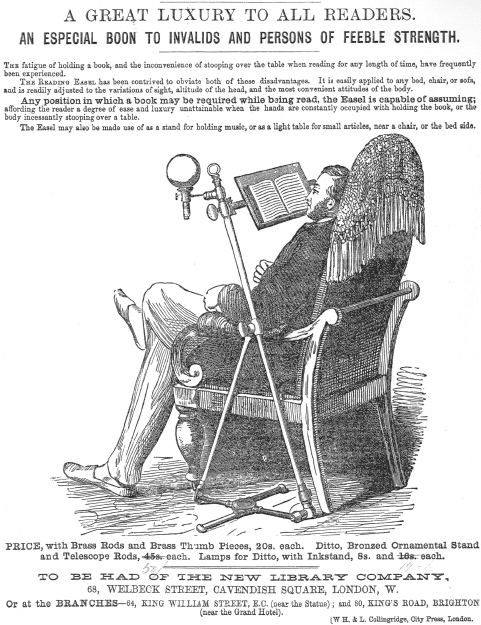

). Advertisements for chairs with bookrests and bedrests add to our general understanding of how books were used (

figure 32.11

). One of the most successful novelty biscuit tins produced by Huntley and Palmers in the 1890s was in the shape of a set of books, complete with colored bindings and tooled titles – and the selection of titles says something about popular (or aspiring) tastes in literature.

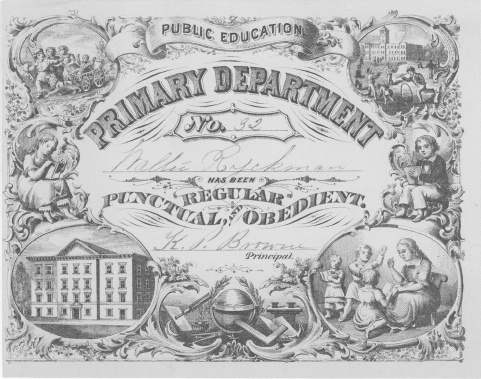

Figure 32.9

Reward of Merit, c. 1870s, private collection.

In our own times, in ironic contrast to the promise of the “paperless society,” our lives are littered with a seemingly ever-increasing amount of ephemeral paper documents that permeate every aspect of our daily existence. “Junk mail,” mostly unwelcome and unsolicited, tempts us to acquire more credit or consume endless fast food. The vast amount of glossy, promotional material, the tedious, bureaucratic forms demanding our attention, the over-packaging of products, and streets strewn with drifts of litter are the bane of modern life. Yet, in their turn, these documents will reflect our age for the future. From the “transient minor documents of everyday life” (Rickards 1988: 7) we can have a direct contact with the past through artifacts that were once central to the functioning of society – the etiquette, protocol, private and business life of past centuries and societies around the world. Maurice Rickards has written that ephemera:

has much more than passing validity. Above and beyond its immediate purpose, it expresses a fragment of social history, a reflection of the spirit of its time … which is not expected to survive, but which can prove to be very useful in research … Ephemera represents the other half of history: the half without guile. When people put up monuments, published official war histories they had a constant eye on their audience and their history would adjust to suit, whereas ephemera was never expected to survive … so it contains all sorts of human qualities which would otherwise be edited out. (Rickards 1977: 9)

Figure 32.10

Packaging label for reading lamp candles, c.1890. Maurice Rickards Collection, Centre for Ephemera Studies, Reading University.

Printed ephemera can document the world of trade and commerce, revealing the bureaucratic manipulation and control of society through rules, regulations, forms, records, certificates, and permissions. Ephemera can reflect the tastes and interests of a period: fashions, hobbies, entertainments, community and social events, sport, travel, art, and culture. The development of education and communication and the opening up of communities and social mobility can be traced through ephemera. After all, most events in life are themselves ephemeral. Often, the only record of great theatrical and dance performances, musical concerts, and art exhibitions are the programs, catalogues, posters, tickets, and flyers that have survived – particularly for experimental or fringe events.

However, for the librarian and archivist, ephemera can pose problems. This material does not lend itself to familiar conventions of classification, storage, and cataloguing. Alan Clinton has observed that:

Traditionally librarians deal with books, museum curators with artefacts, and archivists with manuscripts. Yet at the edges of what was once regarded as the proper concern of each of these are large amounts of printed paper. These materials are often designated nowadays as “ephemera”, and are generally distinguished by being difficult to arrange and to find. (Clinton 1981: 7)

Figure 32.11

Advertisement for the “Reading Easel,” c. 1870s. Author’s collection.

If the ephemera of the past are difficult to handle, then what of the future and the preservation of electronic documents and communications? Perhaps we will need a new definition of the word.

References and Further Reading

The two principal organizations devoted to the study of ephemera are the Ephemera Society of America, PO Box 95, Cazenovia, NY 13035-0095 (

www.ephemerasociety.org

); and the Ephemera Society, PO Box 112, Northwood, Middlesex HA6 2WT, United Kingdom (

www.ephemera-society.org.uk

).

Clinton, Alan (1981)

Printed Ephemera: Collection, Organisation and Access.

London: Clive Bingley.

Fenn, Patricia and Malpa, Alfred P. (1994)

Rewards of Merit: Tokens of a Child’s Progress and a Teacher’s Esteem as an Enduring Aspect of American Religious and Secular Education.

Cazenovia, NY: Ephemera Society of America.

James, Louis (1976)

Print and the People 1819–1951.

London: Allen Lane.

Johnson, John (1933)

The Printer, his Customers and his Men.

London: J. M. Dent.

Lambert, Julie Ann (2001)

A Nation of Shopkeepers: Trade Ephemera from 1654 to the 1860s in the John Johnson Collection.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, John (1962)

Printed Ephemera: The Changing Uses of Type and Letterforms in English and American Printing.

Ipswich: W. S. Cowell (paperback edn., London: Faber & Faber, 1969).

— (1976)

Collecting Printed Ephemera.

London: Studio Vista/Cassell and Collier Macmillan.

McCulloch, Lou W. (1980)

Paper Americana.

New York: A. S. Barnes.

Makepeace, Chris E. (1985)

Ephemera: A Book on its Collection, Conservation and Use.

Aldershot: Gower.

Rickards, Maurice (1977)

This is Ephemera.

Vermont: Stephen Greene.

— (1988)

Collecting Printed Ephemera.

Oxford: Phaidon/Christie’s.

— (2000)

The Encyclopedia of Ephemera,

ed. Michael Twyman. London: British Library.

Roylance, Dale (1992)

Graphic Americana: The Art and Technique of Printed Ephemera.

Princeton: Princeton University Library.

Sullivan, Edmund B. (1980)

Collecting Political Americana.

New York: Crown.

Thomas, Isaiah, Sr. (1813)

Account of the American Antiquarian Society.

Boston: Isaiah Thomas.

Twyman, Michael (1970)

Printing 1770–1970: An Illustrated History of its Development and Uses in England.

London: Eyre & Spottiswood (repr. London: British Library, 1998).

33

The New Textual Technologies

Charles Chadwyck-Healey

In July 1945,

Atlantic Monthly

published an article entitled “As We May Think” by Dr. Vannevar Bush (1890–1974), Director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development. In overall charge of the Manhattan Project, Bush was one of the most powerful scientists in America at a time when a government at war was funding science on an unprecedented scale. In the article, he gives the earliest description of what is now called “hypertext” as he envisages the location of related information in large databases through a system of internal linkages. He also recognizes the need for new technologies to deal with the rapidly increasing output of scientific publishing, and writes: “Professionally our methods of transmitting and reviewing the results of research are generations old and by now are totally inadequate for their purpose.” He goes on to describe a machine, the size of a desk, which he calls the Memex, in which users store information – many thousands of books, journals, and research notes – on microfilm, but regards the ability to locate information instantly as being as important as the storage of the information itself. This has been considered by many commentators to be the conceptual forerunner of the electronic database with hypertext links and searching by keyword. But the Memex is closer to an intermediate generation of machines that was developed in the 1970s in which data stored on microfilm was located through magnetic or optical blips on the edge of the film or between the frames, with motorized winders that took readers directly to the page that they had keyed in.

Bush influenced other computer scientists who became pioneers in their own right. His student, Claude Shannon (1916–2001) laid the foundations of modern information theory, described as one of the great intellectual achievements of the twentieth century,

1

and his paper of 1948, “A Mathematical Theory of Communication,” has been called “the Magna Carta of the information age.”

2

Shannon realized that by treating messages as strings of binary digits, it was possible to separate the message from the medium it traveled on. Out of this new thinking, data compression and error correction gave digital communications a speed and reliability that made computer networks and, ultimately, the Internet possible.

Douglas Englebart read “As We May Think” in the late 1940s and was a believer in Bush’s machine. In the early 1960s, at the Stanford Research Institute, he and colleagues created “NLS” (oN-Line System) which was the first implementation of hypertext and also provided tools such as the computer “mouse,” tele-conferencing, word processing, and e-mail, decades before they came into common use. The NLS team understood the need for a visual user interface at a time when most computer scientists had no direct contact with the computer; input was by punched cards and output was by paper tape.

Ted Holm Nelson was the first to use the term “hypertext” in the mid-1960s. In his second self-published book,

Literary Machines

(1981) he writes: “Individuals, unfortunately just don’t get it. Most or ‘all’ of our reading and writing can or will, in this century, be at instant-access screens.” He goes on: “I will deal simply with reading and writing from screens, and the universe that I think is out there to create – and then explore and live in. Vannevar Bush told us about it in 1945 … but the idea has been dropped by most people. Too blye-sky [sic]. Too

simple,

perhaps.” Later he writes: “The Xanadu™ Hypertext System will be an unusual and probably unique repository in which all forms of material – text, pictures, musical notations, even photographs and recordings – may be digitally stored … and accessible from any port at any time’ (Nelson 1981). Bob Bemer (1920–2004) was not connected with Bush, but from 1960 worked on a standard coding system for storing letters of the alphabet as binary digits. The resulting American Standard Code for Information Interchange (or ASCII) was finalized in 1963, remains in use today, and is fundamental to the creation and exchange of textual information.

While these pioneers were working on the building blocks of information technology, another technology, started before the war, was preparing the way for librarians and their clients to use information stored on media other than paper to be read using a machine. This medium was microfilm.

3

Microfilm publishing for libraries started in 1935 with an edition of

The New York Times

for 1914–18 by the Eastman Kodak Recordak Division. In 1937, Eugene Power (1905–93), the founder of University Microfilms, began selling a microfilm edition of English books published before 1640. In 1939,

The New York Times

became available on microfilm on subscription. From the late 1950s, microfilm publishing grew rapidly as libraries expanded as a result of the growth of higher-education funding. Librarians bought microfilm to save space and because it was inexpensive. It was an important bridge between print and the forthcoming electronic media but, unlike Bush’s vision, was treated as a mass-storage medium and a means of obtaining research materials not available in other formats. It was not until the 1980s that publishers began to provide better access to the contents of large microfilm collections through cataloguing for each title and fuller indexes and bibliographies.

In contrast, the first digital texts were catalogues, bibliographies, and indexes -metadata, information about books, not the books themselves. In 1963, the Jones Report on the use of computers at the Library of Congress led to the birth of the MARC record (Machine Readable Cataloguing) that began to be used in the US in 1965. Thomas J. Watson Jr. bet the future of IBM on the System/360 family of computers that was launched on April 7, 1964, and it was the introduction of third-generation computers with random access disks, CRT (cathode ray tube) terminals, and the ability to send information to other computers or “remote consoles” by phone line that enabled computers to be used for the dissemination of textual information.

At the New York World Fair in 1965 the American Library Association funded a computer-based project called Library/USA. Visitors could ask librarians questions on various subjects and the answers stored in a UNIVAC computer were printed out on a “high-speed” chain printer. While the computer answered questions, it was also used to store stolen car license plates. Operators in one of the New York tunnels would key in the license plates of cars as they passed and the computer would respond before the car reached the waiting police at the other end of the tunnel. In the same year, Ralph Parker (1909–1990), Director of Libraries at the University of Missouri, and Frederick G. Kilgour (1914–2006), then Associate Director of the Yale University Library, submitted a proposal of extraordinary vision for a computerized network of libraries in Ohio to provide a shared cataloguing program based on a central computer store. A book would only have to be catalogued once, and there would also be a union catalogue recording the location of books in libraries throughout the state.

Like Bush, Kilgour had an impressive war record as the highly respected Acting Chairman of the Interdepartmental Committee for the Acquisition of Foreign Publications. He took the Ohio College Library Center (OCLC) from a one-man operation in 1967 to a not-for-profit institution with assets of $13 million, serving more than 1,600 libraries ten years later. He retired in 1995. Today, OCLC is an international cataloguing behemoth accessed online by over 50,000 libraries with a catalogue that contains over 50 million items, still located in Dublin, Ohio.

Also in 1965, Dr. Roger Summit, employed by the Lockheed Missile and Space Company, started to work with NASA to provide better access to the NASA Scientific and Technical Aerospace Reports (STAR). As Bush had foreseen, such was the failure of existing information technologies to keep up with the outpouring of scientific research that there was a common view at Lockheed that it was usually easier, cheaper, and faster to redo scientific research than to determine whether it had already been done (Summit 2002). But in 1968, a year before America put men on the moon, Summit’s team won a major contract from NASA to develop an online retrieval system called NASA/RECON (Remote Console Information Retrieval System), while Summit called the retrieval language itself “Dialog.” Conceived by government-funded “big science,” an important new information technology called “online” had been born. Of equal significance was the ARPANET contract led by the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) which, in 1969, connected four major university computers, one of which was Englebart’s lab at Stanford. Larry Roberts, project director and “father of the ARPANET,” wanted to link computers at ARPA-funded research institutions so that they could share computer resources. But ARPANET was also designed to provide a communications network that would function even if part of it were destroyed by nuclear attack, so that if a direct route was damaged, “routers” would find alternative routes. In the 1970s, the ARPANET became the Internet when a protocol called TCP/ IP was developed by Bob Kahn and Vint Cerf to enable different computers using different software to communicate with each other.

In 1972, the Dialog Information Retrieval Service established by Lockheed began to offer other databases to subscribers with computer terminals and so became the first commercial online service. These included ERIC (Educational Resources Information Center) and NTIS (National Technical Information Service) and were used by a handful of customers. But through the 1970s many scientific and professional databases were added to the rapidly growing Dialog service, and in 1982 Dialog Information Services Inc. was spun out of Lockheed with Summit as President and CEO.

The online vision was compelling: scientists working at home with access through the terminal on their desks to a virtual library that contained a store of information greater than anything that might be found in a physical library. By the end of the 1970s, the still tiny online industry seemed to offer unlimited opportunities through the harnessing of computer technology to the access and distribution of information. Through the 1980s, Dialog did indeed grow at 20–30 percent per year and also had to compete with new competitors, including DataStar created by Radio Suisse, BRS, SDC-Orbit, and many smaller hosts or online providers.

The online industry had huge technical competence and Dialog was profitable from the outset, but the business model was flawed. This only became obvious after the introduction of a new medium, CD-ROM, in the mid 1980s. Dialog offered third-party databases because database publishers could not offer computer access to remote users themselves but, in doing so, Dialog separated the publishers from their end-users. This “separation” included taking a substantial part of the sales revenue – 60 percent was typical. Many publishers found that their online revenues were quite limited and, without being able to know who their users were, were not able to conduct effective sales and marketing themselves, yet suspected that their online host was not conducting effective marketing either.

Another weakness was the complexity of the search process. From the beginning, sophisticated search strategies such as the “logical sum” and the “logical product of logical sums” were possible but unlike the Boolean searching, “And” or “And Not,” this sophistication required the user to be trained to carry out such searches or to use an intermediary, usually a librarian. It was a culture that revered the “priesthood of searchers” (Miller and Gratch 1989: 391) rather than making the user–machine interface easier to use. Online access was charged by the minute and a poorly planned search could be expensive for the library that hosted the service. Libraries either had the choice of charging their clients, which did not fit into the university library ethos, or have intermediaries manage access to the online terminals so that expenditure could be kept within budget, creating another potential barrier between the end-user and the information provider. An exception was LexisNexis, which was launched in 1973 as an online service for lawyers. This was a well-defined market which needed immediate access to legal texts, documents, and regulatory information, and LexisNexis soon became an essential resource in almost every law firm.

In 1988, Lockheed sold Dialog to Knight-Ridder, a US newspaper group, for $353 million. But, in comparison with the growth of CD-ROM publishing, in which Dialog and other online providers also became active, and the explosive growth of the Internet, the use of information delivered online was quite limited, even by scientists and engineers. At the time, the only way to disseminate information held in a computer was by phone line to terminals or “remote consoles.” For publishers, the lack of a convenient, durable, portable vehicle that could be used as a publishing medium was a barrier to creating electronic publications. Electronic publishing would not take off until such a medium became available and the floppy disc was not that medium – it was too fragile, held too little information, and could too easily be tampered with.

One solution in use for the last twenty-five years of the twentieth century was the computer output microfiche (COM). This married two media, digital information and microfilm, and enabled computerized information to be distributed widely at low cost to be read on inexpensive microfiche readers. It was used widely for information that had to be frequently updated, such as library catalogues, parts catalogues, and internal business records, but never became popular as a general publishing medium because few people wanted to read continuous text on the screen of a microfiche reader. By the time “reader printers” that photocopied microfiche pages became sufficiently reliable for general use, the computer revolution was well underway. In the late 1970s, the 12-inch optical disc, also known as the video disc, seemed to have great potential for publishers, but by mid-1980 1.3 million videocassette recorders (VCRs) had already been sold in the US and the ability of the VCR to record programs made it more versatile than the video disc. Video discs failed as a consumer product but were used in training and education because they could display both still and moving images and be controlled or “programmed” by the new microcomputers.