A Donkey in the Meadow (7 page)

Read A Donkey in the Meadow Online

Authors: Derek Tangye

As for myself, as I walked up the path behind them, I was pondering on the value of the moment. Had we ignored the call of the telegram, had we taken the night train to London, we would have returned to Minack with memories of many faces, lunches in hot restaurants, late nights and thirsty mornings, packed tubes and rushing taxis, a vast spending of money, much noise, and yet a feeling of satisfaction that we had at last pushed ourselves again into the circle of sophisticated pleasure; and it was over. Instead we possessed two donkeys; and the magic of this moment.

It is a sickness of this mid-twentieth century that the basic virtues are publicised as dull. The arbiters of this age, finding it profitable to destroy, decree from the heights that love and trust and loyalty are suspect qualities; and to sneer and be vicious, to attack anyone or any cause which possesses roots, to laugh at those who cannot defend themselves, are the aims to pursue. Their ideas permeate those who only look but do not think. Jokes and debating points, however unfair, are hailed as fine entertainment. Truth, by this means, becomes unfashionable, and its value is measured only by the extent it can be twisted. And yet nothing has changed since the beginning. Truth is the only weapon that can give the soul its freedom.

As we reached the stables I had a sudden sense of great happiness, foolish, childish, spontaneous like the way I felt when my parents visited me at school. Free from dissection. Unexplainable by logic. Here were these two animals which were useless from a material point of view, destined to add chains to our life, and yet reflecting the truth that at this instant sent my heart soaring.

‘Do you realise, Jeannie,’ I said, after we had put them safely in the stable and were leaning over the stable door watching them, ‘that people would laugh at us for being sentimental idiots?’

‘Of course I do. Some would also be angry.’

‘Why?’

‘They are afraid.’

‘Of what?’

‘Of facing up to the fact they are incapable of loving anything or anyone except themselves.’

Guerrilla warfare continues ceaselessly between those who love animals and those who believe the loving is grossly overdone. Animals, in the view of some people, can contribute nothing to the brittle future of our computer civilisation, and therefore to love them or to care for them is a decadent act. Other people consider that in a world in which individualism is a declining status, an animal reflects their own wish to be free. These people also love an animal for its loyalty. They sometimes feel that their fellow human beings are so absorbed by their self-survival that loyalty is considered a liability in the pursuit of material ambition. Animals, on the other hand, can bestow dependable affection and loyalty on all those who wish to receive it.

‘It’s odd in any case,’ I said, ‘that whenever one uses the word sentimental it sounds like an insult. Sentimental, before it became a coin of the sophisticated, described a virtue.’

‘In what way?’

‘It described kindness.’

‘Surely in excess?’

‘Only later, in the Victorian age. In those days people were nauseating in the way they fussed over animals, and this was reflected in those awful pictures we all know. Such an overflow of sickly superficiality became a middle-class curse to avoid. Animal haters like to keep alive the idea that Victorian sentiment is synonymous with animal loving. It eases their consciences.’

‘Anyhow, I’m sentimental,’ said Jeannie, ‘and I see no reason why I should be ashamed of it. I only wish human beings were as giving as animals.’

‘Don’t be so cynical!’

‘Well you know what I mean. Human beings can be so petty and mean and envious. You can’t say they are progressing in themselves as fast as the new machines they’re producing.’

‘That’s true.’

‘One can rely on animals to give kindness when one needs it most.’

‘One has naturalness from animals and one is inclined to expect the same from human beings.’

‘And by that you mean we expect too much?’

‘Yes. Animals do not have income tax, status symbols, bosses breathing down their necks.’

Penny came and pushed her nose at us over the door and below her, so that we had to lean over and stretch out an arm to touch it, was the absurd little foal.

‘Anyhow,’ I said, ‘I’m now very glad we’ve given a home to these two. They will amuse us, annoy us in a humorous way, trust us, and give others a great deal of pleasure.’

‘Silly things,’ said Jeannie, smiling.

‘And so let’s be practical. Let’s find Jack, and ask him to discover whether we have Marigold or Fred.’

Jack Cochram, dark with wiry good looks, looked like a Cornishman but was born a Londoner. He was evacuated to Cornwall during the war, and has remained here ever since. His farm has fields spread round Minack, and he and his partner Walter Grose were neighbours who were always ready to help. Walter lived at St Buryan and came to the farm every day. Jack and his wife lived with their children Susan and Janet in the farmhouse at the top of Minack lane, an old stone-built farmhouse with windows facing across the fields towards Mount’s Bay.

After a while in the stable Penny had made it quite plain that she wanted to move, and so we had taken her, Jeannie carrying the foal again, to the little three-cornered meadow where she had had her encounter with the mare. It was close to the cottage and we could keep an eye on them both.

An hour later Jack Cochram arrived, and unfortunately I had been called away. Jeannie therefore led Jack to the meadow and showed him the foal on the other side of the barrier I had erected at the entrance. Jeannie said afterwards that as they stood there, Penny stared suspiciously at them. This was the first time a stranger had seen her foal, and she was on guard. It would have been wiser, therefore, had they waited, allowing Penny to become accustomed to Jack; or if Jeannie had fetched her a handful of carrots to bribe her into being quiet. But Jeannie had been lulled by Penny’s previous serenity, her placid nature, and she failed to understand that Penny might believe her foal was about to be stolen. Jack, in his kindness, jumped over the barrier, picked up the foal, and immediately faced pandemonium.

Jeannie was terrified. She saw Penny rear up, bare her teeth, then advance on her hind legs towards Jack while pawing the air like an enraged boxer with her front legs. Jack quickly put the foal to the ground, but by this time Penny was in such a temper that she failed to see it, and she knocked it flat as she went for Jack. When she reached him she was screaming like a hyena, and he was standing with his back to a broken-down wall in a corner of the meadow. He put up an arm above his head as she attacked him, trying to punch his way clear; and then, seizing a split second, and also swearing I am sure never to investigate the sex of a donkey again, he jumped over the barrier to safety.

Jeannie, meanwhile, was in the meadow herself, kneeling beside the foal which was lying on its side, eyes shut, tongue out, and breathing in gasps. She knelt there stroking its head, Penny somewhere behind her calm again, and thought it was dying. Then she heard Jack cheerfully call to her, unperturbed by his experience: ‘It’s a girl!’

She told me later that Marigold, at this exact moment, opened an eye and flickered an eyelash. Jeannie said it looked so bewitching that she bent down and kissed it at which Marigold gave a deep sigh. Then a few minutes later she struggled to her feet and sturdily went over to Penny who licked her face, then waited as she had a drink of milk. When Jeannie left them they were standing together; and they may well have been laughing together. They had reason to do so.

When our friend, the vet, arrived early in the afternoon, and after we had toasted the health and happiness of Marigold, we learnt that Jack had made a mistake.

Marigold was Fred.

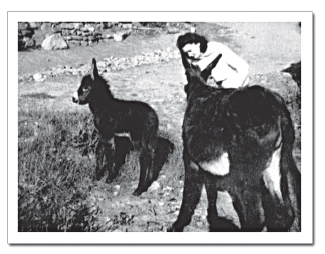

Fred, outside the stable, wonders about taking his first walk . . .

. . . and does so . . .

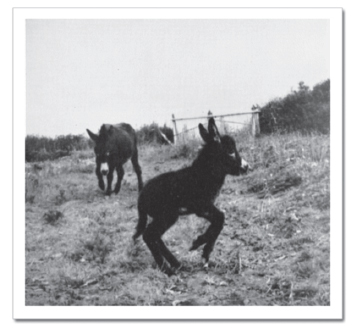

and then has his first gallop

Jeannie’s mother was staying with us when Fred was born, and she was a participant in his first escapade. She it was who had connived with Jeannie to defeat my then anti-cat attitude by introducing Monty into our London household when he was a kitten; and now the happiness that Monty gave us, first in London and then at Minack, was to be repaid in part in the few months to come by Fred. Fred captured her heart from the first moment she saw him; and when she left Minack to return to her home, she waited expectantly for our regular reports on his activities.

He was inquisitive, cheeky, endearing, from the beginning; and we soon discovered he had a sense of humour which he displayed outrageously whenever his antics had embroiled him in trouble. A disarming sense of humour; a device to secure quick forgiveness, a comic turn of tossing his head and putting back his floppy ears, then grinning at us, prancing meanwhile, giving us the message: ‘I know I’ve been naughty, but isn’t it

FUN

?’

He was a week old when he had this first escapade, a diversion, a mischievous exploration into tasting foal-like independence. Perhaps his idea was to prove to us that he could now walk without wobbling, that he was a sturdy baby donkey who could dispense with the indignity of being carried from one place to another. If this was so it was a gesture that was overambitious; and though the result caused us much laughter, Penny on the other hand was distraught with alarm at her son’s idiotic bravado.

I had guarded the open side of the little yard in front of the stables, the side which joined the space in front of the cottage, with a miscellaneous collection of wooden boxes, a couple of old planks, and a half-dozen trestles that during the daffodil season supported the bunching tables. It may have been a ramshackle barrier but I certainly thought it good enough to prevent any excursions by the donkeys, and in particular by Fred. I had omitted, however, to take into account that there was a gap between the legs of one of the trestles suitably large enough for an intelligent foal to skip through. Suitably large enough? It was the size of half the windscreen of a small car, and only after the escape had been made could I condemn myself for making a mistake.

The first to be startled by what had happened was Jeannie’s mother, who was sitting on the white seat beside the verbena bush reading a newspaper. She was absorbed by some story, when suddenly the paper was bashed in her face.

‘Good heavens,’ she said, ‘Fred! You cheeky thing!’

She explained afterwards that Fred appeared as surprised as herself by what he had done, though he quickly recovered himself, danced a little fandango, then set off like a miniature Derby runner down the lane in the direction of Monty’s Leap. Meanwhile there had developed such a commotion in the yard behind the barrier where Penny was snorting, whinnying and driving herself like a bulldozer at the trestles, that Jeannie and I, who were in the cottage, rushed out to see what was happening.

We were in time to see Fred waver on his course, appear to stumble, then fall headlong into a flower bed.

‘My geraniums!’ cried Jeannie. The reflex cry of the gardener. Only flowers are hurt.

‘Idiot!’ I said.