A Donkey in the Meadow (9 page)

Read A Donkey in the Meadow Online

Authors: Derek Tangye

‘Penny! Fred!’

They would stare from afar and make no move.

‘Come on, Penny!’ I would shout again, wanting to prove to my visitors that I was in command. ‘

COME ON

!’

I soon noticed, before he was even a month old, that Fred was usually the first to react. He could be in deep slumber, lying flat on the ground with Penny standing on guard beside him; but when I called he would wake up, raise his head in query, scramble to his feet, pause while looking in my direction, then advance towards me. First a walk, then a scamper.

‘He’s a very intelligent donkey,’ I would then say proudly. A sop to the fact that Penny had ignored me.

But Penny at this time was still a sorry sight, the sores had gone but her coat was still thin. We had to excuse her appearance by repeating the story of how we had found her. We explained her elongated feet by telling how we had waited for Fred to be born before dealing with them, and that now we were waiting for the blacksmith. We chattered on with our excuses and then realised no one was listening. All anyone wanted to do was to fuss over Fred.

‘Aren’t his ears huge?’

‘I love his nose.’

‘Look at his feet! Like a ballet dancer’s!’

‘What eyelashes!’

‘Does he hee-haw?’

I remember both his first hee-haw and his first buttercup. He was a week old when he decided to copy his grazing mother, putting his nose to the grass without quite knowing what was expected of him. He roamed beside her sniffing importantly this grass and that; and then suddenly he saw the buttercup. A moment later he came scampering towards me with the buttercup sticking out of the corner of his mouth like a cigarette, and written all over his ridiculous face was: ‘Look what I’ve found!’

The first hee-haw was to occur one afternoon in the autumn when Jeannie and I were weeding the garden. There was no apparent reason to prompt it. They were not far away from us in the meadow, and every now and then we had turned to watch them contentedly mooching around. And then came the sound.

It was at first like someone’s maiden attempt to extract a note from a saxophone. It was a gasping moan. It then wavered a little, began to gain strength and confidence, started to rise in the scale, and then suddenly blossomed into a frenzied hiccuping tenor-like crescendo.

‘Heavens,’ I said, ‘What an excruciating noise!’

‘Fred!’ called out Jeannie, laughing, ‘what on earth’s the matter?’

At this moment we saw Penny lifting up her head to the sky. And out of her mouth came the unladylike noise which we had already learnt to expect. No bold brassy hee-haw from her. It was a wheezy groan which at intervals went into a falsetto. Here was a donkey, it seemed, who longed to hee-haw but couldn’t. All she could do was to struggle out inhuman noises as her contribution to the duet. It was painful not only to listen to, but also to watch. This was donkey frustration. The terrible trumpet of her son had reawakened ambitions. She wanted to compete with him, but she hadn’t a ghost of a chance.

Meanwhile, as the summer advanced, Penny had developed a role of her own towards the visitors. She was clearly, for instance, used to children and although it was Fred who received the initial caressing attention it was only Penny, because she was full grown, who could give them a ride. Ignored during the first ten minutes, she then became a queen in importance, and she would patiently allow a child to be hoisted on her back, and a ride would begin.

But Jeannie and I soon found that her job was far easier, far less exhausting than ours. One of us had to lead Penny by a halter, and as she would not move without Fred, Fred had to be led along as well. I had bought him a smart halter of white webbing within a few days of his being born, and he never resented wearing it. He wore it as if it were a decoration, a criss-cross of white against his fluffy brown coat giving him an air of importance. One visitor said he reminded her of a small boy who was allowed to wear trousers when all his friends were still wearing shorts.

Up and down the meadow we walked and all the while we had to be on guard against accidents. We had a nightmarish fear that a child might fall off and so while one of us led the donkeys, the other walked alongside holding the rider. We spent hours that summer in this fashion.

There was no doubt, therefore, that the presence of the donkeys was a huge success. People who had come to see Jeannie and me went away happy because they had met Penny and Fred.

‘The donkeys have

made

our day,’ said two strangers who had driven specially from a distance to call on us.

And there were other occasions when I sauntered out of the cottage on seeing strangers draw up in a car, a bright smile on my face.

‘May we,’ an eager voice would ask from the car window, ‘see the donkeys?’

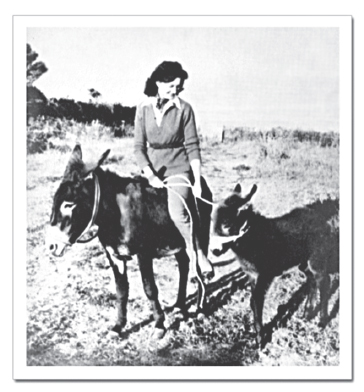

Jeannie, Penny and Fred set out across the stable

An eloquent feature of the donkeys was their stare; and we never succeeded in growing accustomed to it. It was a weapon they used in morose moments of displeasure. There they would stand side by side in a meadow steadfastly watching us, exuding disapproval, condemning us for going about our business and not theirs.

The stare increased in its frequency after the summer and the visitors had disappeared; for Fred, by this time, expected attention like a precocious child film star who believes that adulation goes on for ever. He missed the applause, lumps of sugar, and posing for his picture. He was a prince without courtiers. He was at a loss as to how to fill his day. So he would stare, and hope that we would fill the gap.

‘Why can’t we go to another meadow?’

‘I’d like a walk.’

‘Oh dear, what is there to do?’

And when finally we relented, yielding to the influence of the stare, and dropped whatever we were doing, and decided to entertain him, Fred would look knowingly at Penny.

‘Here they come, Mum. We’ve done it.’

Penny’s stare was prompted by a more practical reason. True she enjoyed diversions, but they were not an innocent necessity as they were for Fred. She was old enough in experience to be phlegmatic, her role as a donkey was understood; she had to be patient, enduring the contrariness of human beings, surprised by the affection she was now suddenly receiving, and yet prepared it might end with equal suddenness. She didn’t have to be amused. All she had to remember was to have enough milk for Fred, and that the grass was losing its bite. Her stare was to induce us to change to another meadow or to take her for a walk, not for the exercise, but for the grasses and weeds of the hedgerows. A walk to her was like a stroll through a cafeteria.

It did not take much to amuse Fred. He liked, for instance, the simple game of being chased, although he and I developed together certain nuances that the ordinary beholder might not have noticed. There was the straightforward chase in which I ran round a meadow panting at his heels, Penny watching us with an air of condescension, and Fred cantering with the class of a potential racehorse; and there was a variation in which I chased them both, aiming to separate them by corralling one or other in a corner. This caused huge excitement when my mission had succeeded with Penny in a corner and Fred the odd man out. He would nuzzle his nose into my back, then try to break through my outstretched arms, snorting, putting his head down with his ears flat, and giving the clear impression he was laughing uproariously.

He loved to be stalked. In a meadow where the grass was high I would go down on my hands and knees and move my way secretly towards him. Of course he knew I was coming. He would be standing a few yards off, ears pricked, his alert intelligent face watching the waving grass until, at the mutually agreed moment, I would make a mock dash at him; and he would make an equally mock galloping escape. This was repeated again and again until I, with my knees bruised and out of breath, called it a day.

I think, though, that our most hilarious game was that of the running flag. I would get over the hedge to the meadow or field he was in, then run along the other side holding a stick with a cloth attached high enough for him to see it. It baffled him. It maddened him. He would race along parallel to unseen me whinnying in excitement; and when, to titillate his puzzlement, I would stop, bring the stick down, so suddenly he saw nothing, nine times out of ten he would rend the air with hee-haws. Of course he knew all the while that it was a pretence; and when I jumped back over the hedge to join him he greeted me with the cavorting of an obviously happy donkey.

These were deliberate games. There were others which came by chance. Electricity had at last come to the cottage and on one occasion I saw a Board Inspector running across the field with a joyous Fred close behind him. The Inspector, I am sure, was glad when he reached the pole he had come to inspect, and could speedily climb out of reach.

It was a fact that Fred enjoyed the chase as much as being chased. He was fascinated, for instance, by Lama and Boris. As soon as he saw the little black cat he would put his head down, move towards her, struggling to free himself from the halter with which I was holding him. Or if Lama had entered the meadow in which he was roaming, his boredom would immediately vanish. Why is she here? How fast can she run? Let me see if I can catch her.

And yet I never saw any evidence that there was viciousness in his interest. Lama, because of her trust in all men and things, gave him plenty of opportunities to show the truth of his intent; and his intent seemed only to chase to play. It was the same with Boris. On one occasion Fred escaped from his halter, saw Boris a few yards from him and, head down close to white-feathered tail, proceeded to chase Boris round the large static greenhouse in front of the cottage. The waddle and the hiss of Boris was distressing to behold and to hear, but I found myself watching without fear that Fred might do any harm. It was clear that Fred was only nudging him. Here is my nose, there your tail. Go a little faster, old drake.

The donkeys now spent much of their time in the field adjoining the cottage, and it was here that Fred had his first major fright. The field was so placed that the stare could be imposed upon us in a particularly effective fashion. It was a large field sloping downwards to the wood with a corner which was poised shoulder-high above the tiny garden. Hence when the donkeys came to this corner, which was often, they looked down at us. They could even see into the cottage.

‘The donkeys are wanting attention,’ Jeannie would say as she sat in a chair by the fire, ‘shall I deal with them or will you?’

There were other occasions when they chose to stand in the corner purely, I am sure, to emphasise the toughness of their lot. When there was a storm with rain beating down on the roof and the wind rattling the windows they would stand in view of our comfort. Two miserable donkeys who could easily have found shelter under a hedge. Two waifs. Fred with his fluffy coat bedraggled and flattened against his body like a small boy’s hair after a bathe. Penny, years of storm suffering behind her, her now shiny black coat unaffected, passing on her experience to Fred.

‘Put your head down, son. The rain will run off your nose.’

But the day that Fred had his fright was sunny and still, an October day of Indian summer and burnished colours, the scent of the sea touching the falling leaves, no sadness in the day. Fred, now a colt not a foal, was enjoying himself grazing beside Penny, nibbling the grass like a grown-up, when under the barbed wire that closed the gap at the top of the field rushed a boxer.

Had Boris and Lama witnessed what followed no doubt they would have laughed to themselves . . . a taste of his own medicine . . . that is how

we

feel when he comes thundering after us. The difference, however, was that the boxer was savage. It chased Fred as if it were intent on the kill. It had the wild hysteria of a mad wolf. It ignored the galloping hooves. It tried to jump on Fred’s back, teeth bared, its ugly face ablaze with primitive fury. And all the while Fred raced round and round the field bellowing his terror like a baby elephant pursued by a tiger.

I had arrived on the scene at the double to find Jeannie already there running after the dog with Penny trumpeting beside her; and a man walking unconcernedly across the field towards the cottage. The contrast between calm and chaos was startling.

‘I have lost my way,’ said the man when he saw me, ‘can you direct me to Lamorna?’

His nonchalance astounded me. My temper was alight.

‘Is that your dog?’ I shouted back.

‘Yes,’ he smiled, ‘he’s having a good time.’

‘

GOOD TIME

? What the hell are you saying? Look at that baby donkey, look at your dog!’ I was incoherent with rage. I raised my arm and wanted to hit him. ‘How dare you come through private property without a dog like that on a lead!’

‘He doesn’t like a lead.’

It was fortunate that at this precise moment I saw that the boxer had broken away from the chase, that Jeannie, after a moment’s soothing of Fred, was hastening to my support. The sight restrained me.

‘Get that dog, then get off my land!’