A Drake at the Door (18 page)

Read A Drake at the Door Online

Authors: Derek Tangye

And perhaps the wonder of their loyalty and their enthusiasm was the way they struggled on day after day with this transplanting of twenty thousand seedlings. So many have a task and give up when the task challenges their tenacity. It is easy to be excited about a job which is new, or when the end gives quick reward. Here they were faced by a huge field of hot dry soil, so hot that even Jane complained on some days that her bare feet were walking on hot cinders; and into this hot field they had to bring alive again, after digging them from the seed beds, the early-flowering wallflower upon the success of which so much of the flower season depended.

Each had a pail in which they mixed soil and water until it was a muddy mess, and each seedling was dipped into it. They wrapped the mud around the roots so that there was a cocoon of moist mud. A monotonous job. Hour after hour, day after day; and in the evening Jane would report to me the number that had been planted.

‘A record, Mr Tangye,’ she would say, proud that they had indeed planted more than ever before, ‘we’ve done twelve hundred today!’

Twelve hundred, it wasn’t much. But they had first to dig up the seedlings from the seed bed and this, using a trowel, was a tedious business. The ground was hard like cement, and their hands blistered, and their wrists ached from the jab of the trowel as it scooped out the long tap roots. They were always so meticulous. They never made a show of doing a job. Slipshod did not belong to their vocabulary, and so if progress was slow it was never time wasted. They both aimed for success in everything they were ever asked to do, not for some flamboyant gain; just for the sheer personal pleasure they gained from doing their best.

They were lucky, I suppose, in that they both had a feel for flowers, and a love of the earth, and a communion with blazing suns and roaring winds; and they had minds which found excitement in small things, the sight of a bird they could not identify, or an insect, or a wild plant they had found in the wood. They were always on the edge of laughter, of pagan intuition, of generosity of spirit. They were not cursed by the sense of meanness, of jealousy of others, of defiance.

They wanted to love. There was so much in life to be exultant about and I never knew either of them, even in fun, say a harsh thing about anyone.

And yet Shelagh, I feel, suspected the identity of her mother. Indeed she may have met her once, although as a stranger, when she delivered a note to a house in the village where visitors were staying. And there was another time when Shelagh, looking for somewhere to live, was inadvertently given the address of her mother by someone; and Shelagh wrote innocently asking if there was a room to spare. There was not.

These incidents, for all I know, may have happened while she was at Minack, and others as painful as well; and this would explain why there were days in which she appeared silently to sulk and be moody, days on which Jane, Jeannie and I would work hard to win from her that delicious grin.

‘What’s wrong, Shelagh? Cheer up!’

‘I’m all right.’

Jeannie and I were not so foolish as to pry into these moods ourselves. We left it to Jane. And Jane was too subtle ever to bring the mood to bursting point by asking too many questions or by appearing self-consciously aware that something was wrong. If the first approach was turned down by Shelagh, she did not persist. They would work alongside each other in long silences, comfortable silences, and then I would look again and see them chatting to each other, and I would know that Shelagh’s mood had passed.

‘What was wrong?’ I would ask Jane later.

‘She didn’t say.’

Both of them were secretive and why not? It is impertinence, I think, for those with experience to question the young. The young are a race apart with magical values and standards, with mysterious frustrations and victories, free from repeated defeats, fresh, maturing, bouncing into danger, propelled by opposites, frightened, confused by what is told them. And their lecturers, I believe, are those who, having failed in the conduct of their own lives, recoil to the hopes of their youth, reliving ambitions by pontificating, hurting the sensitive young and being laughed at by the others. Experience should be listened to by the young. It should never be inflicted on them.

Even in high summer Shelagh would be thinking of Christmas, and if one of us wanted to enliven a moment of the day, Shelagh would be asked:

‘How many days to Christmas?’

‘One hundred and twenty-seven.’

‘Did you hear that, Jane?’

‘Yes, and I bet she knows what presents she’ll give already!’

Shelagh spent the year planning these presents but this coming Christmas was a special one for her. It was the first year that she had earned a wage above subsistence level, and she confided to Jeannie one August morning when she was busy dusting the house: ‘I’ve always promised myself that I would give the most wonderful presents possible to all those I love at the first Christmas I had the money to do so.’

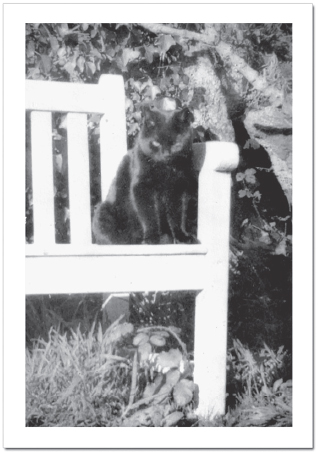

One of our presents from her that coming Christmas was a picture of Lama sitting on the white seat by the verbena tree. Lama, because she is all black, is a most difficult subject to photograph; she dissolves into all normal backgrounds. But Shelagh, noting this, waited one day until Jeannie and I had gone out and lured Lama to sit on this particular white seat and took the photograph with her box camera. The photograph was taken in August and she did not tell even Jane; and the secret was hers until we undid the coloured wrapping and found Lama, eyeing us, in a neat frame.

Lama loved her. Lama, because she had been born wild, did not know how to play and Shelagh set out to teach her. It was extraordinary how, in those first months, we could dangle anything in front of Lama, or tease her with a twig, or play the games associated with cats, and receive no response whatsoever. She just didn’t understand what we were trying to do.

But every lunch hour, if Shelagh’s pet mouse had not arrived before her, Lama would sit on her lap as Shelagh munched her sandwiches, taking any portion which was offered her and then, as if paying her bill, would tolerate the efforts of Shelagh to make her play; a piece of raffia tickling her nose or a pencil pushed between her paws. In time, with our help as well, Lama woke up to the pleasure that cats are able to give human beings.

Shelagh was phlegmatic towards animals and birds, and yet touchingly loving. If, for instance, I expressed concern at the prospect of Lama coming face to face with her pet mouse, Shelagh would appear quite unperturbed.

‘My mouse would hide in my shirt.’ And she said it as if it were the most ordinary thing in the world that a mouse should hide in a girl’s shirt.

And yet I sometimes saw a ghoulish side to her, a macabre sense of humour which relished an unsavoury situation. I remember once coming into the flowerhouse and finding the mouse on her shoulder while Lama had entered the door ahead of me.

‘Look out, Shelagh,’ I said.

She gave me a wide grin, showing no anxiety whatsoever.

‘Just think,’ she said lasciviously, ‘if Lama

did

catch Patsy how wonderful her crunches would sound!’

She delighted in murder stories and the more gruesome the better. And so sometimes, when work progressed and we felt in the doldrums, one of us would sparkle a minute by telling Shelagh that we had read about a particularly brutal death in the papers; and her eyes would light up in mock excitement.

‘Tell me more!’

And then, if the facts themselves were not horrific enough for her, we would invent some that were; and we would all end up sharing the same ghoulish laughter.

This apparent callousness was, of course, superficial, though I suspect it was also a form of armament. She was afraid of her own gentleness, and she needed to bolster herself sometimes by pretending she was tough. She had to prove to herself that she was independent. She was not a rebel in the sense that she had a chip on her shoulder; she was just tired of always being under an obligation to others, and she wanted to have her own personality and be free.

She had a wonderful way with sick birds, a fearless, uncomplicated tenderness towards them. There was one morning when she arrived half an hour late and instead of bicycling she had walked.

‘Had a puncture, Shelagh?’ I called, as I saw her coming up the lane. Then I noticed she was holding something under her coat, and when she came up to me she showed me a wood pigeon. She had found it lying on the side of the road a few minutes after she had started out for work; and so she had gathered it up and, because it would be difficult to carry if she bicycled, she had left the bicycle behind.

We took the pigeon straight away to the Bird Hospital at Mousehole. Its wing was broken after being shot, and a pellet had to be extracted. In due course, however, the wing began to heal and the pigeon regained its strength; and there came a day when Shelagh received a note from the hospital that the pigeon had been set free. She was brimming over with happiness, and from then on whenever a pigeon passed overhead she used jokingly to call out:

‘There’s my pigeon!’

She once had the extraordinary experience of working in one of the greenhouses when a merlin hawk dived through a half-opened ventilator, landed at her feet, and knocked himself out. Heaven knows how he managed to do it or what he was after, but there was Shelagh peacefully weeding the tomatoes when she suddenly felt a rush of air, heard a plomp, and saw on the ground beside her an inert bundle of feathers.

It so happens that birds seldom fly straight into the panes of a greenhouse from the outside. They swerve away in time. Indeed I have only known the gloriously coloured bullfinches appear blind to glass; but they, thank heavens, are migrants in this part of the world. I do not often have to pick up their beautiful bodies.

The trouble starts when a bird goes into a greenhouse and does not know how to get out and in its panic hurtles itself against the glass until it is senseless. Oddly enough it is usually the yellowhammers which are the victims. Time and again I have found a dead or dazed yellowhammer. A wren is far too nimble-minded ever to hurt itself and although wrens seem permanently to haunt the greenhouses both in winter and summer, I have never seen an injured one. Robins usually ignore our greenhouses and I never saw our Tim in one, although he was happy in the cottage. Thrushes, too, do not venture inside. But the blackbirds have a glorious time when the tomatoes are red and ripe. They gorge on the fruit, earning our curses, but we are ready to give them a tomato in return for a song.

Shelagh treated the merlin in the same way she and Jane always treated the dazed yellowhammers. She filled the cup of her hand with water, and in it she dipped the merlin’s beak, opening the beak with her fingers so that the water trickled down its throat.

It is an astonishingly quick way to stage a bird’s recovery. There it is resting in your hand seemingly helpless . . . and you have the sweet pleasure of watching it slowly come to life. You are alone with it. It is quiet. You feel the tiny claws tickling, then touching, then clutching your hand. And then suddenly when all kindness has matured, it is away . . . towards the wood, up into the blue sky, or down along the moorland valley. Here is triumph. Here is truth.

And because the merlin fell by Shelagh he did not have to wait to be helped. Had he chosen a moment to perform his miracle of escape when the greenhouse had been empty, hot, dry, unfriendly to anyone or anything which was injured, he would have died. But Shelagh was there to save him. And she could not keep the victory to herself. So when the merlin began to show life again, and Shelagh knew the danger of moving him was over, she brought him to us in the cottage.

‘Look at this,’ she said with her delicious grin, and the merlin clasping her hand with his claws. He was awake now. He knew he was alive. He would go soon.

But he stayed long enough for me to get one of the bird books so that I could read out its identification: ‘Upper parts are slate-blue, the nape and under parts warm, often rufous, buff, the latter with dark streaks.’

It is such a moment which quells worry, and in a wondrous flash transforms depression into exultation. There I saw before me not only the majesty of a bird returning to the wild but the stream, the clear, sparkling stream, the dawning stream of a girl’s happiness. If only it could have remained for ever.

Both of them had the same stature. Jane, like Shelagh, had the mind which instinctively helped the helpless. Here were these two at Minack, sustaining Jeannie and me with the glory of enthusiasm. In this place we loved so much were these two who shared the pleasures we, so much older, felt ourselves. The young voices calling for their hopes amongst the gales and the rain and the heat. So far to go. So passionately willing to give to the present.

Jane was always more sure of herself than Shelagh because she had been loved for herself, since she could remember. And yet, in her way, Jane was as vulnerable. She loved the weak; but when she demonstrated this love she liked to dispense an atmosphere of drama. It was fun to do so. And so it was in this mood she arrived at her work one summer’s morning and disclosed an exciting piece of news.

‘Mr Tangye,’ she said breathlessly, ‘a Muscovy drake spent the night in my bedroom. We want to find a home for him. Can he come to you?’