A Higher Form of Killing

Read A Higher Form of Killing Online

Authors: Diana Preston

CONTENTS

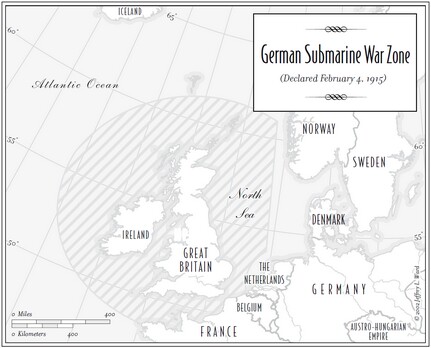

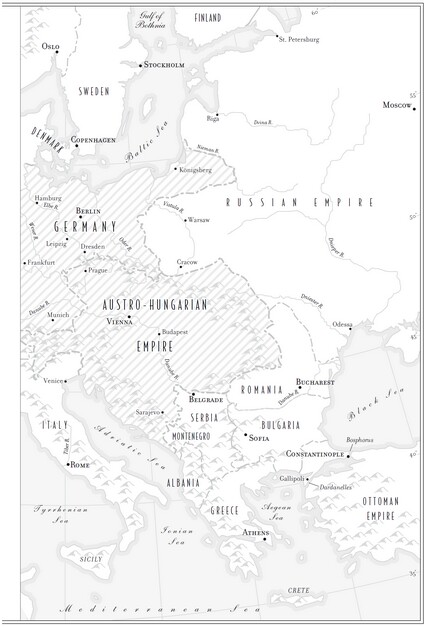

Europe on the Eve of World War I

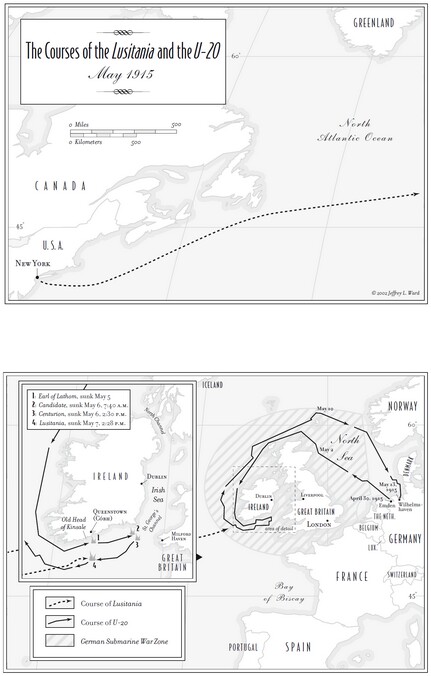

The Courses of the Lusitania and the U-20

1 “A Flash of Lightning from the North”

8

“Something That Makes People Permanently Incapable of Fighting”

10

“This Filthy Loathsome Pestilence”

12

“They Got Us This Time, All Right”

13

“Wilful and Wholesale Murder”

16

“Order, Counter-Order, Disorder!”

18

“Do You Know Anything About Gas?”

19

“Zepp and a Portion of Clouds”

21

“Each One Must Fight On to the End”

22

“Weapons of Mass Destruction”

Appendix The

Lusitania

Controversies

During peacetime a scientist belongs to the world but during wartime he belongs to his country.

—The words of Fritz Haber, the Nobel Prize–winning German chemist who developed poison gas as a weapon and personally supervised the world’s first use of it on April 22, 1915, in a chlorine gas attack by the German army against French and Canadian troops at Ypres. Haber is later said to have commented: “In no future war will the military be able to ignore poison gas. It is a higher form of killing.”

Lusitania. Missing a baby girl, fifteen months old. Very fair curly hair and rosy complexion. In white woollen jersey and white woollen leggings. Tries to walk and talk. Please send any information to Miss Browne, Queens House, Queenstown.

—Notice in a shop window in Queenstown (Cobh), Ireland, seeking information about a child lost in the torpedoing without warning on May 7, 1915, by the German submarine

U-20

of the British Cunard liner

Lusitania

with the loss of 1,198 people including 128 citizens of the then-neutral United States.

The principal objective is extremely simple and thoroughly German. They wish to kill as many people and to destroy as much property as they possibly can.

—Editorial in the

Times

, June 2, 1915, commenting on the first aerial bombing raid on London on May 31, 1915, by a German zeppelin.

These quotations encapsulate three milestone events that occurred in a single six-week period during the initial year of the First World War and forever changed the nature of warfare. Each of the three was important in its own right. By the end of the war nearly 30 percent of German artillery shells contained poison gas, and gas was a major component of all belligerents’ armories and strategies arousing particular fear and aversion as it still does today. The sinking of the

Lusitania

highlighted the potency of the submerged submarine as a commerce raider capable of destroying large tonnages of merchant shipping. This would be demonstrated both later in the First World War and in the Battle of the Atlantic in the Second World War when U-boats came close to cutting off imports of food and war matériel to Britain. In geopolitical tems the

Lusitania

was described as failing to bring two hundred U.S. civilians to Liverpool in 1915 but in 1917 bringing two million U.S. soldiers to France. This was because it provoked a long-running dispute between the United States and Germany about the latter’s submarine tactics that led to the U.S. declaration of war in April 1917, and consequently and inexorably to Germany’s defeat. The bombing raids on London’s civilians were the precursor to the Second World War German blitz on London and the Allied destruction by area bombing of Hamburg, Dresden, and Tokyo.

However, viewed together, the three attacks acquire even greater significance and resonance. They represent a cataclysmic clash between the laws on the conduct of warfare laid down in the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 under which all three were illegal and the new weapons developed by technology under the impetus of war. In doing so they epitomized the sharper edge science had given to the eternal dilemma as to how far the ends can ever justify the means. They also posed the question how the laws of war could be universally rather than unilaterally enforced, particularly given that in agreeing the Hague Conventions, politicians had felt compelled to ignore the pragmatic reservations of men such as British admiral “Jacky” Fisher, American admiral Alfred Mahan, and German admiral Alfred von Tirpitz. Fisher, the father of the Dreadnought battleship and a delegate at the first Hague Conference, summed up such views: “The humanising of war, you might as well talk about humanising hell! The essence of war is violence!”

The British and their allies had been forewarned of each attack. German army deserters and Allied agents clearly indicated the imminent probability of a gas attack on the western front near Ypres, providing considerable and—as it turned out—accurate detail. Indeed, the prospect of the use of gas was so widely discussed that the

Times

reported it thirteen days before it was deployed. The German embassy in Washington placed an advertisement in the American newspapers on the day the

Lusitania

sailed from New York warning passengers against traveling on British ships. In the

New York Times

it appeared next to Cunard’s announcement of the

Lusitania

’s schedule. The British Admiralty knew separately from decoded German targeting information that the

Lusitania

was at risk. The British authorities had recognized the potential for zeppelin raids on London from the beginning of the war.

Nevertheless, the authorities took little action to forestall these known threats. In part this was due to the relatively few defensive measures available at this stage in the war (no gas masks, no depth charges, no sonar, no fast-climbing fighters) and in part due to complacency. Even more significantly, those in high positions refused to believe in the face of all the evidence that Germany’s political leaders and its military commanders would countenance the unleashing of attacks that in addition to being illegal would shatter long-cherished concepts of honor, decency, and “civilized” behavior in warfare.