A History of China (76 page)

Read A History of China Online

Authors: Morris Rossabi

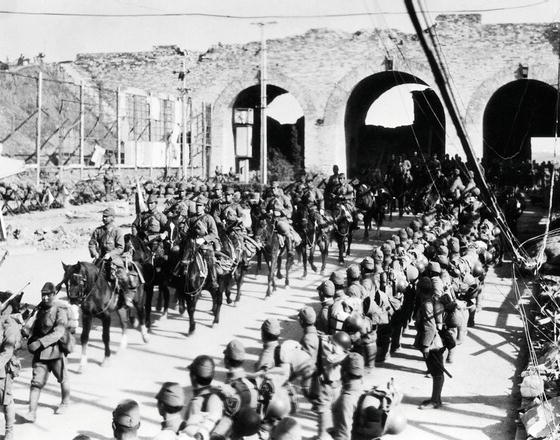

Figure 11.3

Invading Japanese forces moving into Nanjing, 1937. © Bettmann / CORBIS

Having not faced significant opposition in their occupation of Manchuria, the Japanese were emboldened to take additional steps to dismember China. In 1933, they moved into northern Hebei province, the area closest to Manchuria and, more ominously, the province nearest Beijing. Shortly thereafter, they supported the Mongol prince Demchugdongrob (1902–1966) in his effort to break away and to establish an independent country of Inner Mongolia. Some of their scholars helped the government by emphasizing the distinctions between the Chinese and the Mongolians and by promoting Mongolian ethnic identity. Prince De (as Demchugdongrob would be known to the Chinese) became the so-called ruler of much of Inner Mongolia but with Japanese advisers and commanders making the crucial decisions. Like Puyi, Prince De was virtually a Japanese puppet. Japan appeared to threaten many northern Chinese provinces. One incident after another followed until a confrontation between Chinese and Japanese soldiers in July of 1937 at the Marco Polo Bridge, ten miles west of Beijing, led to the outbreak of war. Within the next few months, Japanese troops, despite considerable loss of life, occupied much of China’s east coast. When these soldiers entered the capital city of Nanjing, they were primed to exact revenge against the Chinese. They unleashed an assault on Chinese soldiers and civilians and men and women that the Chinese labeled the Nanjing Massacre. The number of dead, wounded, and raped Chinese is still in dispute, but that there was a seemingly uncontrolled rampage seems unquestionable.

Meanwhile, Chiang Kai-shek did not surrender and simply moved farther and farther inland. The Japanese had apparently hoped to break down resistance and to set up friendly puppet governments without having to use an enormous number of soldiers to pacify the Chinese interior. In any event, they did not have sufficient troops to occupy the whole country. It is not clear whether Chiang’s retreat to the interior with him winding up in Chongqing was a deliberate strategy or merely a response to repeated Japanese threats and his own loss of men and territory. However, the net effect was to prevent a Japanese victory, leading to a protracted stalemate in the war. Yet Chiang’s control over China had indeed receded. Japan dominated much of China’s east coast, Manchuria, Inner Mongolia, and sections of north China; Xinjiang and other border areas were virtually independent; and the communists controlled an increasing part of the northwest. The Japanese recruited Wang Jingwei, one of Chiang’s most ardent opponents in the late 1920s, to serve as the alleged governor of the central sections of China (including the Shanghai and Nanjing regions) – or, more accurately, to be the Japanese puppet in the region, detaching still more territory from Chiang’s control.

Chiang’s position was thus fragile. He did not fear a ground invasion by Japanese forces, but enemy planes pummeled Chongqing and other sites. The USSR initially provided some assistance, but by the end of the 1930s and early 1940s it had turned its attention to threats posed in the West. After the summer of 1939, it could focus almost entirely on the West because it had helped Mongolia to end incursions on its territory by defeating the Japanese at the battle of Nomonhan (or Khalkhin Gol, to the Mongolians). Marshal Gyorgy Zhukov (1896–1974), one of the great Russian heroes of the Second World War, earned his first successes in this battle. After this battle, because the USSR no longer feared the opening of a second front against Japan, it could marshal its troops in the West, which translated into reduced support for Chiang. The USA provided minimal economic assistance, and Chiang’s main American supporters were the pilots recruited by Claire Lee Chennault (1893–1958). This volunteer group, which eventually came to be known as the Flying Tigers, challenged Japanese superiority in the air and offered some protection for Chongqing.

Chiang had not dealt with the serious problems that plagued his government in Nanjing. Corruption and nepotism appeared to be endemic, and the differences between rich and poor were still wide. Taxes on the peasantry were often high and capricious. Little was done to alleviate the peasants’ poverty and suffering, which often translated into famines. Workers were exploited and lacked government support in the form of legislation to control the minimum wage and maximum hours. A few workers, especially those who labored in the arms industry, responded by developing a real class consciousness and solidarity. Although the war complicated efforts to introduce reforms or changes, the lack of progress on land reform, protection of industrial workers, and implementation of the Marriage Law (which had been enacted in 1931 and had abolished arranged marriages and offered more rights to women) undercut support for the Guomindang. In addition, a seeming reluctance to employ its best troops against the Japanese alienated patriotic Chinese.

HE

P

ACIFIC

W

AR, THE

C

OMMUNISTS, AND THE

G

UOMINDANG

After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the USA began to play a role in the Pacific. President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed General Joseph Stilwell (1883–1946) as commander of the US forces in east and Southeast Asia to represent US interests in China and to collaborate with Chiang Kai-shek. As the war progressed, Stilwell became increasingly disenchanted with the Guomindang. He was appalled by the government’s incompetence and corruption. Derisively referring to Chiang as “Peanut,” he repeatedly but unsuccessfully pressed the Guomindang leader to use his best forces against the Japanese. Stilwell also faced opposition from Claire Chennault, who emphasized air power rather than ground forces. Limited resources meant that a decision was needed about these differing strategies. Both Chiang and the major US decision makers opted for air power and started to build airports and to seek planes from the USA, stymieing Stilwell, whom Roosevelt eventually recalled from China.

The Chinese communists did not achieve a true united front with the Guomindang and faced other difficulties as well. Not only did they not forge an alliance with the Guomindang but also the armies of the two Chinese parties, on occasion, clashed, with considerable loss of life and damage to the land. Each side blamed the other for these counterproductive hostilities, and the Guomindang went one step further by denying the communists in the northwest products they required. Nazi Germany’s attack on the USSR in June of 1941 exacerbated the communists’ problems because the Russians, intent on their own defense, could provide almost no assistance. The British, having surrendered Singapore to the Japanese, were also preoccupied, which prevented them from helping the Chinese.

Nonetheless, the communists did engage the Japanese. Their forces attacked Japanese positions in north China but did not make substantial progress. Instead, these battles provoked the Japanese into harsh reprisals on the Chinese population, sometimes leading to destruction of whole communities. With such a relatively weak position, the communists could not afford to alienate people they ruled by initiating radical policies. They needed to be pragmatic rather than ideological. Their leaders did not advocate confiscation of land owned by landlords or rich peasants, nor did they institute significant social reforms.

The Communist Party itself underwent dramatic change, as it identified its new leadership and clarified and supplemented its ideology. Party membership had increased spectacularly, but the communist hierarchy believed that many new recruits lacked knowledge of and dedication to communism. The party had grown from the ten thousand or so who survived the Long March to about 2.8 million in 1942, the year that Mao Zedong initiated efforts that would make him the virtually undisputed leader of the party. He started a so-called Rectification Campaign, which lasted from 1942 to 1944, to weed out those whom he considered to be ignorant of communist ideology, and this led to a decrease in party size. Many of the new recruits had been peasants from the communists’ base in Yan’an and the surrounding regions. Party leaders started schools to train those who retained their party affiliation in proper behavior and ideology and welcomed urban youth, intellectuals, and professionals who had been entranced by the communists’ message and had moved to Yan’an. The schools instructed party members to be egalitarian, to live simply, to maintain ties with the local population, and to adhere strictly to Marxist–Leninist–Maoist ideology. It was significant that Maoism now came to the fore. Mao perceived himself to be on a par with Marx and Lenin as a thinker, and he wanted to distinguish himself from the Soviet leaders, some of whom he began to distrust.

Perhaps the main thrust of the Rectification Campaign was “thought reform,” a means of “purifying” party members. They met in discussion groups as part of the so-called brainwashing. Each participant was criticized and then wrote a self-criticism about his or her divergence from Marxist–Leninist–Maoist thought and deviation from party instructions. After considerable group discussion, the participant would write a self-confession in which he or she apologized for past mistakes. The campaign spilled over into an attack on supporters of Mao’s previous rivals and on independent-minded intellectuals (a group Mao often considered to be insufficiently loyal to him) who were hesitant to acquiesce to the party’s and his dicta. This was the first of a series of purges that would characterize Chinese communist history. Mao also brought communist cadres back to schools.

His lectures to the assembled groups were then published. In addition to the standard Marxist ideology, he charted new ground in his speeches. He again set forth his reasoning for communist reliance on support from the peasants for victory. In his work on art and literature, his instructions to writers and artists were that they represent the proletariat. Their works could not be neutral. Mao denigrated the concept of art for art’s sake. He insisted that art and literature always reflected particular class interests. Artists and writers needed to support the working classes’ interests. “Socialist realism” had to guide their works. They had to portray society realistically but also needed to point to the socialist future by describing the values and attitudes of a new socialist mankind. It was no accident that simplistic but colorful posters imprinted with party slogans became popular works of art. Literature and art that did not subscribe to the strictures of socialist realism would not be tolerated, and writers and artists who deviated from this model would have their works censored and could be imprisoned or, in extreme cases, hounded to death. Mao’s formulations on these issues became party dogma and solidified his position as party leader.

As the Pacific War began to turn in favor of the Allies, principally the Americans, both the Guomindang and the Chinese communists were affected. From late 1942 on, US forces had gradually been defeating the Japanese and compelling them to abandon one Pacific island after another, moving ever closer to the Japanese islands. By 1944, US airplanes were bombarding Japan itself. General James Doolittle (1896–1993) had already pounded Tokyo and other cities as early as April 18, 1942, but by 1944 the raids were more frequent and deadlier. The most important contribution of both Chinese parties was to pin down Japanese forces in China, improving the USA’s chances in the conflict with Japan. However, the actions of the Guomindang and the Chinese communists differed. The Guomindang continued to be accused of harsh treatment and exploitation of peasants and of forced conscription into the army. Income disparities and corruption persisted in the Guomindang-controlled regions, and morale in these areas was damaged. The Guomindang’s campaigns against the Japanese were lackluster, with Japanese troops often inflicting heavy damage on Guomindang forces. Meanwhile, the communists appeared to have a disciplined, loyal, and efficient army. Having created greater stability toward the last few months of the Second World War, Mao Zedong could start to implement more dramatic changes, including a more sustained land reform that benefited the poor peasantry. The communists seemed so much more competent and dedicated that outside observers were sympathetic to them. Some Americans, including government officials, considered them to be more reliable partners than the Guomindang. Several presented favorable reports about the communists to President Roosevelt and portrayed them as “agrarian reformers.” This was a crucial moment in US–Chinese relations because there was a possibility of an entente between the USA and the so-called agrarian reformers. However, Chiang Kai-shek ruled out collaboration with the communists, and Roosevelt abided by that decision.

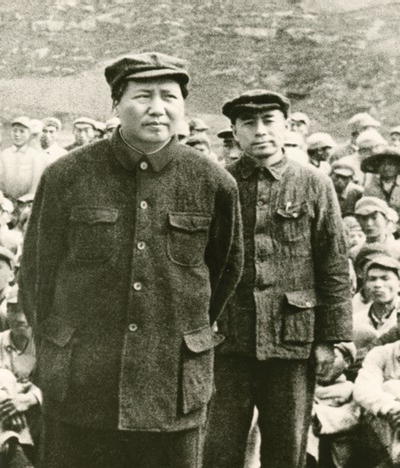

Figure 11.4

Mao Zedong (left) and Zhou Enlai (right) in Yan’an in northwest China, 1945. Photo: akg-images