A History of the Crusades (34 page)

Read A History of the Crusades Online

Authors: Jonathan Riley-Smith

The history of the Near East as a whole in the period from the 1090s to the 1290s was dominated politically by the fall of Seljuks, the rise and fall of the Khorezmians, and the coming of the Mongols. The same period saw the fairly widespread political triumph of the partisans of Sunnism over the Shi‘is. In particular, the territorial power of the Assassins was destroyed first in Iran and then in Syria. Although it would be seriously misleading to label this period of Near Eastern history ‘the Age of the Crusades’, it still remains true that the history of Syria and Egypt in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries is primarily the story of the growing unity of those Islamic lands in response to the challenge posed by the existence of the Latin settlements.

There were no Muslims left in Jerusalem after crusaders had slaughtered or taken captive the entire Muslim population in 1099; Christian Arabs from the Transjordan were later invited to settle in Jerusalem to help repopulate the city. In some places, such as Ramla, the population fled in advance of the crusaders. In other towns and villages they chose to stay. Frankish settlement brought better policing to the coastal areas and a degree of protection for the agriculturalists from marauding bedouin and Turkomans. The Muslims who remained in crusader territory had to pay a special poll tax, reversing the situation in Muslim lands where it was the Christians and Jews who had to

pay the poll tax, or

jizya

. On the other hand, unlike Latin Christians, they did not pay the tithe. Ibn Jubayr, a Spanish Muslim pilgrim to Mecca who, on his way home, passed through the kingdom of Jerusalem in 1184, claimed that the Muslim peasantry were well treated by their Frankish masters and paid fewer taxes than peasants under neighbouring Muslim rulers. He even thought that there might be a long-term danger of them converting to Christianity.

Nevertheless, the evidence does not all run one way and, even in some of those areas where the Muslims had elected to stay, there were subsequent revolts and mass exoduses. There were Muslim rebellions in 1113 in the Nablus region, in the 1130s and 1180s in the Jabal Bahra region, in 1144 in the southern Transjordan, and later on in the century there were sporadic peasant uprisings in Palestine which coincided with Saladin’s invasions. In the 1150s, after several protests against the exactions and injustice of the lord of Mirabel, the inhabitants of eight villages in the Nablus region decamped en masse and fled across the Jordan to Damascus. These and earlier refugees from the kingdom of Jerusalem and the other Latin principalities settled in the cities of the interior, especially in certain quarters of Aleppo and Damascus, where they constituted a vociferous lobby for the prosecution of a jihad which would restore their homes to them. They looked for a leader.

Ilghazi, the first plausible candidate to present himself, was a member of the clan of Artuq, one of the many Turkish tribal groups who had taken advantage of the break-up of the Seljuk empire to carve out small territorial principalities for themselves. He was governing Mardin when, in 1118, he was asked by the citizens of Aleppo to take over in their city and defend it against Roger of Antioch. Ilghazi took oaths from his Turkoman following that they would fight in the jihad and he went on to win the first victory in the Muslim counter-crusade at the Field of Blood. However, in various respects Ilghazi failed to conform to the ideal image of a leader of the jihad. Not only was he a hard drinker, but he was really more interested in consolidating his own power around Mardin than he was in destroying the principality of Antioch. Ilghazi died in 1122

without having lived up to the hopes the Aleppans had invested in him.

Imad al-Din Zangi, the

atabak

of Mosul (1127–46), was more successful at presenting himself as the leader of the jihad. The thirteenth-century Mosuli historian Ibn al-Athir was to write that if ‘God in his mercy had not granted that the atabak [Zangi] should conquer Syria, the Franks would have completely overrun it.’ Zangi moved to occupy Aleppo in 1128. Its citizens, fearful both of threats by the Assassin sect within the city and of the external threat from the Franks, did not resist him. Like so many

atabak

s nominated by the Seljuks, Zangi made use of his position to establish what was effectively an independent principality in northern Iraq and Syria. In this principality, Zangi imitated the protocol and institutions of the Seljuk sultans of Iran. Like the Seljuks, he and his officers sponsored the foundation of

madrasa

s and

khanqa

s.

The

madrasa

, which had its origins in the eastern lands of the Seljuk sultans, was a teaching college whose professors specialized in the teaching of Quranic studies and religious law. It was an entirely Sunni Muslim institution and indeed one of the most important aims of such colleges was to counteract Shi‘i preaching.

Khanqa

s (also known as

zawiya

s) were hospices where Sufis lodged, studied, and performed their rituals. Sufi preachers and volunteers were to play an important part in the wars against the crusaders. The proliferation of

madrasa

s and

khanqa

s in Syria under Zangi and his successors was part of a broader movement of moral rearmament, in which both rulers and the religious élite devoted themselves to stamping out corruption and heterodoxy in the Muslim community, as part of a grand jihad which had much wider aims than merely the removal of the Franks from the coastline of Palestine. The

Bahr al-Fava

‘

id

, discussed above, faithfully reflects the ideology of the time. Besides preaching holy war against the Franks, it counsels its readers against reading frivolous books, sitting on swings, wearing satin robes, drinking from gold cups, telling improper jokes, and so on.

Although Muslim pietists, particularly in Aleppo, looked to Zangi as the man of destiny and the new leader of the jihad, for

the greater part of his career he did little to meet their expectations and in fact he spent most of his time warring with Muslim rivals. He particularly hoped to add Muslim Damascus to his lands in Syria, but Damascus’s governor, Mu‘in al-Din Unur, was able to block Zangi’s ambitions by making an alliance with the kingdom of Jerusalem. However, in 1144, thanks to a fortunate though unplanned concatenation of circumstances, Zangi did succeed in capturing the Latin city of Edessa. The historian Michael the Syrian lamented the capture of the city: ‘Edessa remained a desert: a moving sight covered with a black garment, drunk with blood, infested by the very corpses of its sons and daughters! Vampires and other savage beasts ran and entered the city at night in order to feast on the flesh of the massacred, and it became the abode of jackals; for none entered there except those who dug to discover treasures.’

But according to Ibn al-Athir: ‘when Zangi inspected the city he liked it and realized that it would not be sound policy to reduce such a place to ruins. He therefore gave the order that his men should return every man, woman and child to his home together with all the chattels looted from them … The city was restored to its former state, and Zangi installed a garrison to defend it.’

Zangi, who was assassinated by a slave in 1146, was succeeded in Aleppo by his son Nur al-Din, and it was Nur al-Din who, with the assistance of an eager pro-jihad faction within the walls of Damascus, made a triumphal entry into that city in 1154. There Nur al-Din commissioned a

minbar

, or pulpit, to be installed in the Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, in expectation of that city’s imminent reconquest by his armies. However, the conquest of Egypt proved to be a more urgent priority. Ascalon had fallen to the Franks in 1153, giving crusader fleets a port within striking distance of the Nile Delta. The Fatimid caliphs of Egypt had become the impotent pawns of feuding military viziers and ethnically divided regiments. There were some in Egypt in the 1150s and 1160s who favoured coming to terms with the kingdom of Jerusalem in order to secure its assistance in propping up the Fatimid regime, while others rather looked to Nur al-Din in Damascus for help in repelling the infidel.

In the end it was a Muslim army sent by Nur al-Din which succeeded in taking power in Egypt and in thwarting Christian ambitions in the region. But Nur al-Din himself gained very little from the success of his expeditionary force. The largely Turkish army he sent to Egypt was officered by a mixed group of Turks and Kurds, and it was one of the Kurdish officers, Saladin (or Salah al-Din) from the Kurdish clan of Ayyub, who took effective control as vizier of Egypt in 1169. In 1171 Saladin took advantage of the death of the incumbent caliph of Egypt to suppress the Fatimid caliphate and from then on the symbolically significant Friday sermons in the congregational mosques were preached in the names of the Abbasid caliph of Baghdad and of Nur al-Din, the sultan of Damascus. In Egypt, Sevener Shi‘ism had been the affair of an élite and, even then, there had been many powerful Sunni Muslims, Christians, and Jews. Although there was little resistance to the enforced return to Sunnism, Saladin and his successors in Egypt were careful to foster orthodoxy by founding

madrasas

and by patronizing Sufis.

Saladin was ever ready to offer declarations of loyalty to Nur al-Din, but he was less forthcoming about actually providing his master with the money and military assistance which he was repeatedly asked for. When Nur al-Din died in 1174, Saladin advanced into Syria and occupied Damascus, displacing Nur al-Din’s son. The greater part of Saladin’s career as ruler of Egypt and Damascus is best understood first in terms of his unsuccessful attempts to take Mosul from its Zangid prince and secondly in terms of his drive to create an empire to be ruled by his clan. He had to satisfy his Ayyubid kinsmen’s expectations by carving out appanages for them. This clan empire was largely created at the expense of Saladin’s Muslim neighbours in northern Syria, Iraq, and the Yemen. Throughout his whole career, an enormous part of Saladin’s resources were devoted to fulfilling the expectations of kinsmen and followers. Generosity was an essential attribute of a medieval Muslim ruler.

However, Saladin was also under pressure of a different kind

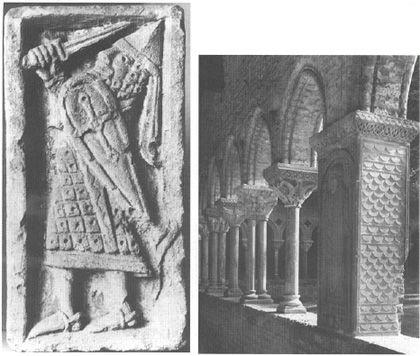

left:

PLATE

1 A knight in a twelfth-century relief. Most of the principal elements of the knight’s equipment arc depicted, hut not the lance. The spurs indicate that the favoured method of fighting was on horseback; but it was also possible to operate on foot, as most of the knights on the First Crusade were forced to do when their mounts died.

right

:

PLATE

2 Moissac, an abbey in south-western France which Urban II visited during his tour of France and which possessed a famous collection of relics from Jerusalem.

Monasteries such as Moissac, which were often the largest and most renowned religious establishments in their localities and which could draw on well-established pools of lay respect and support, played an important part in propagating the crusade appeal.

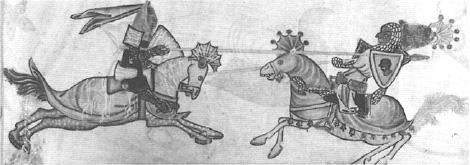

PLATES

3 Among the marginal drawings in the Luttrell Psalter is this visualization of a combat between a suitably villainous Saracen and a knight. The English royal arms on the knight’s shield suggest that the drawing depicts the legendary duel between Richard I and Saladin on the Third Crusade.